Here’s an emergency-room story: An intoxicated woman comes in after falling on her outstretched hand. A fractured wrist is diagnosed. The bones are aligned, the wrist splinted, the pain controlled, and a follow-up arranged. She returns a few nights later, this time severely beaten by her boyfriend.

What did we miss the first time? How? Why? This case highlights the complicated and precarious nature of medical decision-making. One area of focus between Alpert Medical School and the RISD Museum involves engaging with art objects to illuminate our mind at work, revealing vulnerabilities and pitfalls in thinking that can have catastrophic consequences when caring for patients.

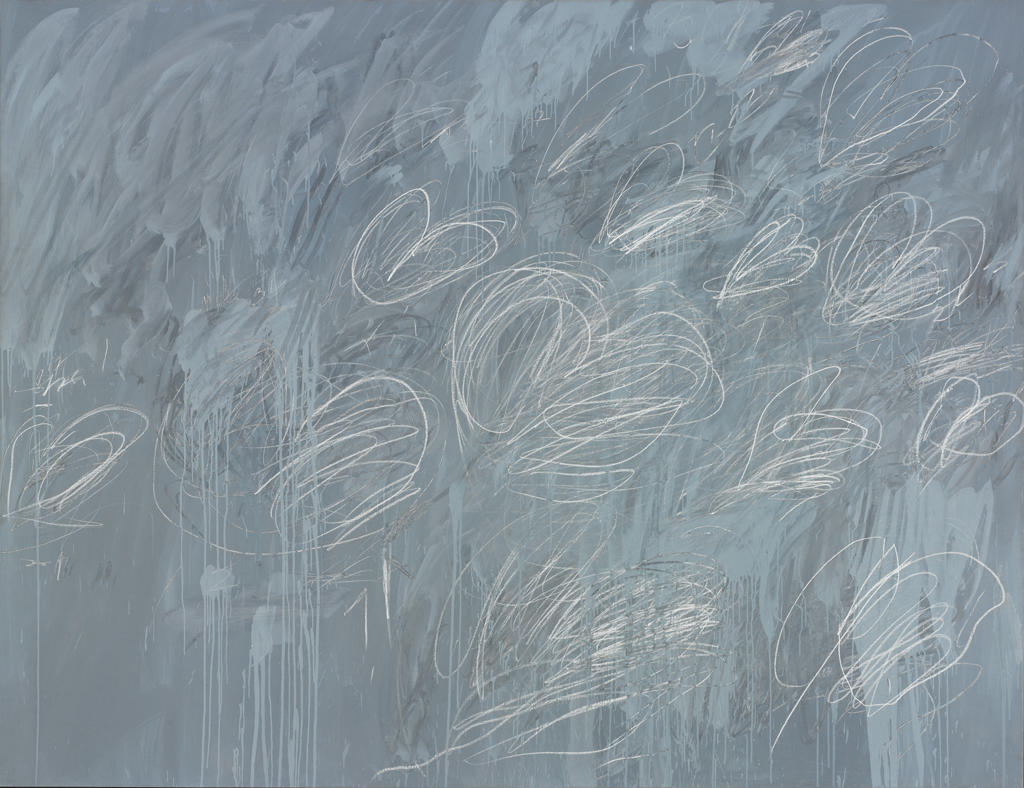

The process of understanding patients in the emergency department can feel strangely similar to standing before this Twombly. Where do you begin? What my eyes consider a safe landing place might be different than yours.

The students’ first impulse is to find something recognizable. Are those hearts, or maybe butterflies soaring off the canvas? They try to make sense of the messiness, as if it’s a pirates map and somewhere there’s an X with the secret treasure.

We used this painting frequently in our teaching, first with first-year medical students six years ago. By “we” I refer to a collaboration that began with Dr. Kevin Liou, a former medical student; RISD Museum educators, led by Sarah Ganz and Hollis Mickey; and myself.

The museum educators guide the students with questions or tasks. For example, select one small area of the painting and sketch the positive space—the area with marks or information. Then, sketch the negative space—the spaces around the marks, supposedly without information.

In this manner, students begin to see how negative space is always relational, in reference to something, and how marks and their absence can communicate ideas. We ask students to make an abstract drawing of a conversation they had, capturing what they considered was the positive space in the dialogue and the negative space.

Through questions, analysis, and crude art-making, we make connections back to what is unsaid or unsayable in medicine. Where we set our eyes, and what we value as relevant information, are decisions we make before we begin making decisions.

This session took place over a few hours. It represents a glimpse of one session, but serves to demonstrate the type of innovative teaching taking place between the RISD Museum educators and Alpert Medical School.

When we began our collaboration six years ago, most of the collaborations between museums and medical schools focused primarily on building observational skills, diagnostic acumen, and pattern recognition. Or they aimed at fostering reflection and empathy. They produced excellent work, and the resulting publications inspired and set a standard for what has become an emerging and exciting field for education and scholarship.

That said, we set out with different goals in mind. We wanted students to become aware of how they think, and to begin to work with the uncertainty, ambiguity, and messiness of clinical practice.

How can we challenge students to think about how they think when they still lack the requisite knowledge?

Works in the RISD Museum represent complex bodies of information. Like patients, they can elicit strong emotions and forge powerful connections, as well as appear inscrutable, overwhelming, and unappealing.

Sarah and Hollis introduced and modeled an exercise called “description, deduction, speculation” that is based upon the work of Jules Prown, a professor in the Department of Art, American Art, and Material Culture at Yale University. Drawing from constructivist and inquiry-based pedagogical approaches, the exercise at the RISD Museum used open-ended questions to generate individual observations rather than right or wrong answers.

Students were first asked to describe the museum object, creating a descriptive inventory of what they see. Then they were instructed to make deductions, to interpret their observations, and to draw on their prior knowledge and experiences.

Sometimes what students believed to be an objective finding was really a deduction. For example, a painting with man and women with two young children was described as a family, when we don’t know that for certain. These assumptions aren’t uncommon in clinical practice. The patient with chronic dental pain is often assumed to be a drug seeker, or an intoxicated woman with the broken wrist “fell” because she was drunk.

Finally, students were asked to speculate—to take their descriptions and deductions and make imaginative leaps about broader and deeper ideas, such as what the object says about the creator or the values and beliefs of the period.

Confronted with the Twombly or another abstract painting whose meaning is unclear, students tended to focus on familiar shapes while neglecting other aspects of the work. Students are often eager to move quickly, jumping to conclusions without considering other possibilities. In this exercise, they gain experience with cognitive shortcuts such as premature closure, and learn how that can lead to medical mistakes.

By helping students slow down and take in the full picture, they learn how to work through ambiguity and their own emotional reactions to not knowing, and how their beliefs, biases, and prejudices can influence which problems they chose to address and how they influence the decision-making process.

The last part of the exercise involved asking students to reflect on the experience by drawing a visual representation of their thinking process. This type of open-ended inquiry is a vital part of clinical practice. It’s easier in the museum space for many reasons. Lives aren’t at stake and students are not being graded, so participants are relieved of the pressure to find the correct answer. Since there are no right or wrong answers, the museum is a safe place to learn how to think divergently.

In another exercise, students sit before this sarcophagus with an image of the object overlaid with vellum paper. They mark places that are perceived as offering answers or information. They also mark areas where they find questions or ambiguity, as well as areas of conflict. By sharing their perspectives with a partner, students consider how narratives are constructed, how another person may generate a different story from the same material, and how our perspectives can be altered by someone else’s words and perceptions. Over a few hours, they develop a tangible feel for knowledge as materials, how fragments make up the whole, and the many ways the stories we create are influenced by personal history, bias, and the perspectives of others. Along the way, we hope students develop comfort with situations that offer more questions than answers.

We remind students that even evidence-based medicine involves interpretation, and that psychology literature shows that the confidence people have in their beliefs is not always a judgment on the quality of the evidence but a judgment of the coherence of the story the mind has managed to construct.

What began six years ago as a session for first-year medical students in the pre-clinical years has sprouted to include a multitude of projects whose reach extends from undergraduate Brown University students, Alpert Medical School students, residency-training programs, and health-care providers from many disciplines out in clinical practices. (For more details, see below.)

Our work has been presented at regional and national meetings, in a diversity of disciplines that includes medicine, humanities, and museum educators. Most recently, we were honored to present our work as part of a landmark conference in New York City at the Museum of Modern Art, which brought together a community of museum and medical educators from the United States, Canada, and beyond.

We are presently addressing issues of assessment. Many studies measure students immediately after a session or a course—and we’ve done some assessment in this manner—but what we’re really interested in is how these experiences might influence students’ thinking on the wards or once they enter residency training.

It’s not only the use of museum objects but the chance to work with museum educators that makes this innovative method so important. More than knowledge of art, the educators share their methods as skilled teachers. Students can learn from their willingness to tolerate silence and ask open-ended questions, and from their ability to engage with a host of medical persons who are often skeptical at the outset. Students also see modeled how instructors from different backgrounds work together and engage in difficult conversations.

Art educators have much in common with medical educators. In “Visible Thinking: Using Contemporary Art to Teach Conceptual Skills,” Julia Marshall described two kinds of learning that are developed through making and viewing art: declarative knowledge (knowledge of content) and procedural knowledge (knowledge of how to apply that content). Teaching how to apply knowledge is as important as teaching the ”facts.” And what counts as important information is often found in the negative spaces.

(Versions of this post presented at MedEd talks, Alpert Medical School at Brown University, Providence, RI, November 17, 2015, and the Art of Examination: Art Museum and Medical School Partnerships, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, on June 8, 2016.)