As a part of its new Clinical Arts and Humanities Program, the Alpert Medical School partnered with the RISD Museum to create the workshop series From Galleries to Wards. This elective was designed specifically for students in Brown University’s Program in Liberal Medical Education (PLME), a combined baccalaureate-M.D. program spanning eight years of undergraduate and medical studies. Workshop participants Samuel Kase and Cia Mathew reflect on their experience.

Galleries to Wards

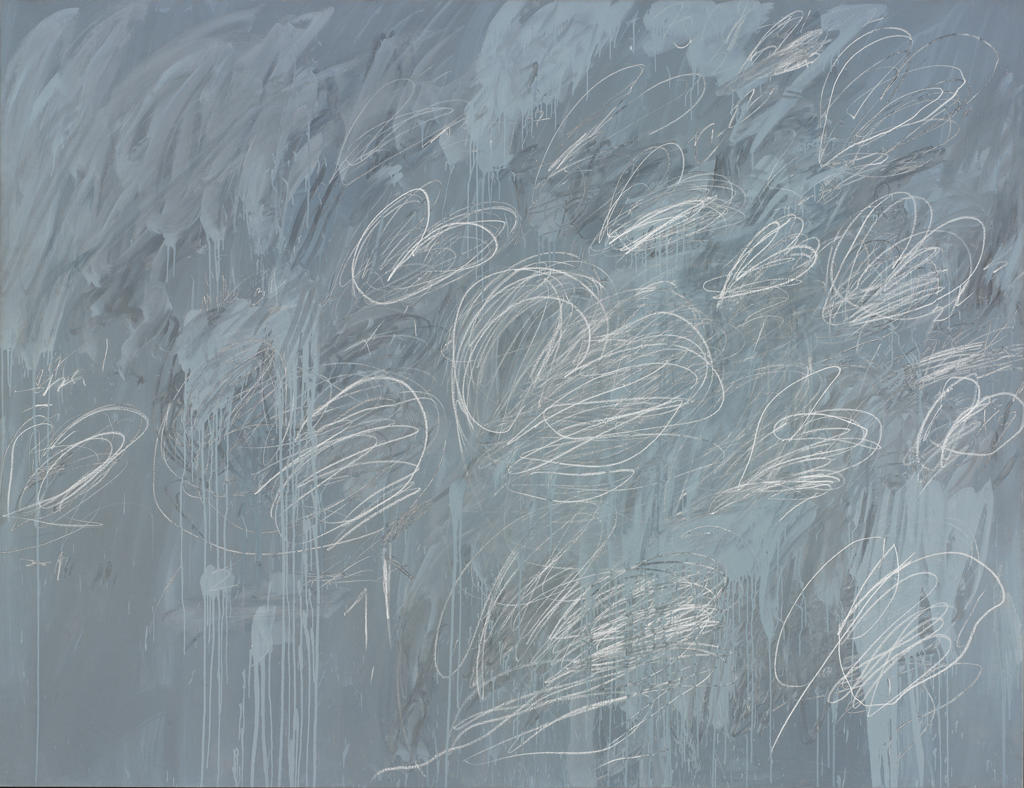

A massive chalkboard with scribbles and smudges in vague heart shapes was mounted in front of me. Around me sat several students, a museum educator, and an emergency-room physician. As we discussed the abstract art in front of us, I quietly wondered if I was the only one in the circle who did not see the connection between scribbles and medicine. As we stared deeper into the chalkboard scrawls of Cy Twombly’s Untitled (1967), I found myself getting lost and frustrated at the same time. There was so much not said with this piece. There was so much left unclear. It was a mess. Twombly lives in the tension between knowing and not knowing, between communication and lack of communication. His blackboard scribbles irritated me, and now I believe that is exactly what he intended to do. He forced me sit in the unknown. As a premed student, I’ve been taught to swallow as much information as possible. To absorb my biology textbooks and memorize chemistry compounds. But when I’m given a creative mess, I have no idea what to do.

Cy Twombly

American, 1929 - 2011

Untitled, 1968

Oil and crayon on canvas

200.7 x 261.6 cm (79 x 103 inches)

Albert Pilavin Memorial Collection of 20th-Century

American Art 69.060

This seminar reminded me that the medical profession is not always black and white, with all information included. There will be unknowns, there will be grays, and there will be facts that have not been communicated. When dealing with patients, there is weight in what they do not say, along with what they do say. A woman that repeatedly comes in for simple colds may be trying to bring attention to a painful home situation. A depressed teen may be dealing with more than what’s immediately revealed. Furthermore, not all communication is verbal. Twombly’s piece conveys a powerful, frenzied energy without using bright hues or an explanatory title. Emotions and sentiments are being expressed in an unconventional way. As a physician, communicating with a patient goes beyond words; it’s also about body language, eye contact, and tone.

I started this course without a clue how contemporary art would help me become a better physician, but the lessons Twombly and my instructors taught me will make me a better physician—one who can create wholeness when given vagueness, and one who can communicate trust and warmth with more than words. Biology can get a doctor only so far. It’s the pursuit of humanity, of creativity, and of communication that makes a doctor a healer.

Cia Mathew

Brown University, literary arts / pre-med, 2014

Medicine in the Galleries

On a cold February night earlier this year, I was joined by three instructors and five other students as we commenced the first of five sessions examining ideas related to both art and medicine. When I see the words art and medicine together, the common phrase “practicing the art of medicine” immediately comes to mind. This is of special interest to me, as it’s the foundation of my independent concentration—medical humanities—at Brown University. When I learned about the From Galleries to Wards seminar held at the RISD Museum, I thought that perhaps it would help me figure out what is meant by this saying. How is medicine an art?

I was not entirely sure what to expect that first night; I was told to bring nothing but an open mind. The group met in a classroom for brief introductions but soon headed to the galleries for an exercise focused on a Roman sarcophagus from the 2nd century, with special attention given to the relief. Sitting beside the coffin with clipboards, tracing paper, and an image of the side of the coffin, we were asked to annotate, differentiating the parts of the structure that were vital to explaining the piece’s overall meaning. After an intense period of observing and interpreting the sarcophagus, we discussed our results. Although some general overlap existed, I was amazed to find that each person had a very different answer. While one found the outstretched arm of a male soldier on the left to be the focus of the relief, another saw the woman on the right to be in control of the scene. Perhaps even more interesting was the fact that one person’s question or uncertainty about a part of the piece could be another individual’s main focus. These ambiguous parts lead to questions, and parts that may be of importance to new meanings. Through this discussion, we were able to fill in each other’s gaps and wed our interpretations to produce a more complete understanding of the sarcophagus. This is just one of many enlightening assignments during our five sessions.

As I reflect on the seminar, I am brought back to my original question. The exercises we worked on required observation, interpretation, understanding, communication, cooperation, empathy, and creativity, and it’s in these themes that we see how the practice of medicine mirrors the practice of art. Each of us worked on the sarcophagus exercise by observing and interpreting the piece. Only after we felt we understood the coffin did we come together to discuss our findings. We debated our discoveries and asked further questions to promote each other’s understanding. This same method can be seen in the clinical setting: a patient is brought to the hospital with a problem, a team of doctors and nurses works together to observe and study the patient, discuss their findings, and come to the most appropriate and logical solution. After discussions with the patient, they embark on a course of treatment.

In recent years, medicine sometimes has been dominated by economics and science, and estranged from the thoughtful, individualized analysis and interpretation that marks its relationship to art. By giving me a better understanding of art, From Galleries to Wards also gave me new insight into the practice of effective and compassionate medical care.

Samuel Kase

Brown University, pre-med, 2015