OBJECT LESSON

“Our cradleboards are living beings”

A Conversation with

Vanessa Paukeigope Jennings

and Carl Jennings

Images

Ka’igwu (Kiowa) Cradleboard, ca. 1900

Wood, leather, beadwork, and brass tacks

Length: 111.1 cm. (43 3/4 in.)

Museum Works of Art Fund 44.610

Ka’igwu (Kiowa) Cradleboard, ca. 1900

Wood, leather, beadwork, and brass tacks

Length: 111.1 cm. (43 3/4 in.)

Museum Works of Art Fund 44.610

Ka’igwu (Kiowa) Cradleboard, ca. 1900

Wood, leather, beadwork, and brass tacks

Length: 111.1 cm. (43 3/4 in.)

Museum Works of Art Fund 44.610

Ka’igwu (Kiowa) Cradleboard, ca. 1900

Wood, leather, beadwork, and brass tacks

Length: 111.1 cm. (43 3/4 in.)

Museum Works of Art Fund 44.610

Ka’igwu (Kiowa) Cradleboard, ca. 1900

Wood, leather, beadwork, and brass tacks

Length: 111.1 cm. (43 3/4 in.)

Museum Works of Art Fund 44.610

1

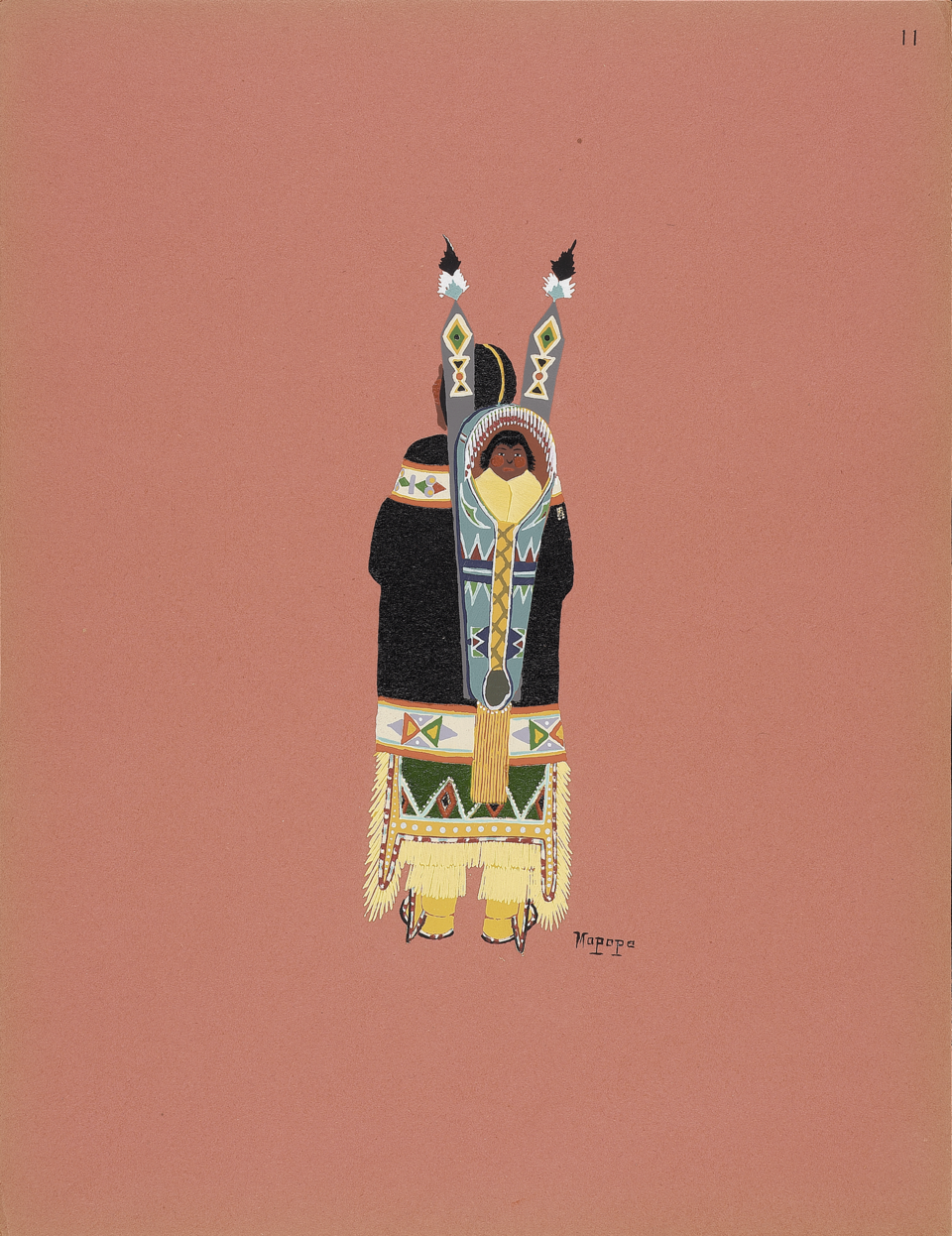

FIG. 1

Ka’igwu (Kiowa) Cradleboard, ca. 1900

Wood, leather, beadwork, and brass tacks

Length: 111.1 cm. (43 3/4 in.)

Museum Works of Art Fund 44.610

This text is condensed from transcriptions of telephone conversations that took place March 5 and April 20, 2021, between Vanessa Jennings, Carl Jennings, curator Kate Irvin, and editor Amy Pickworth.

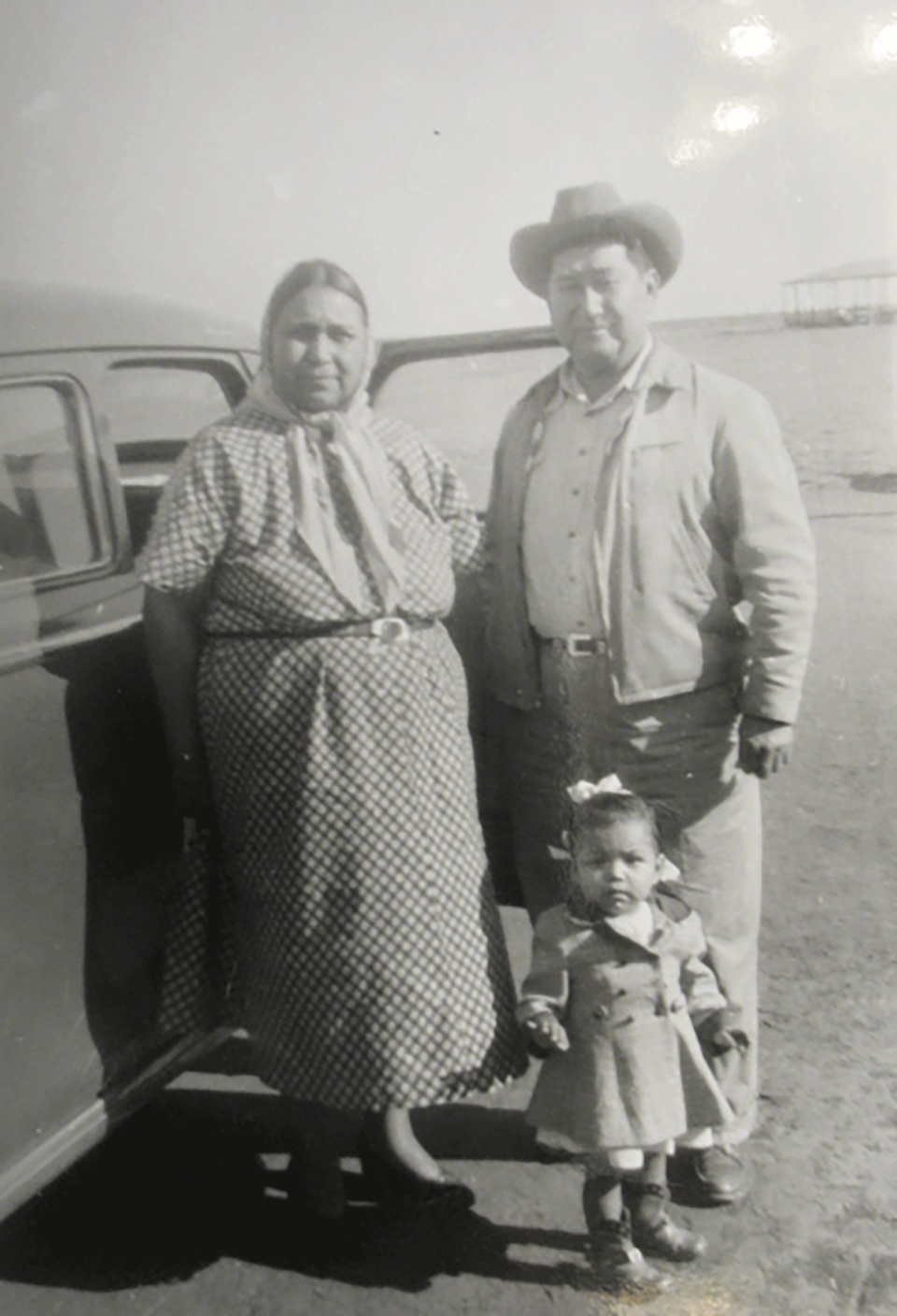

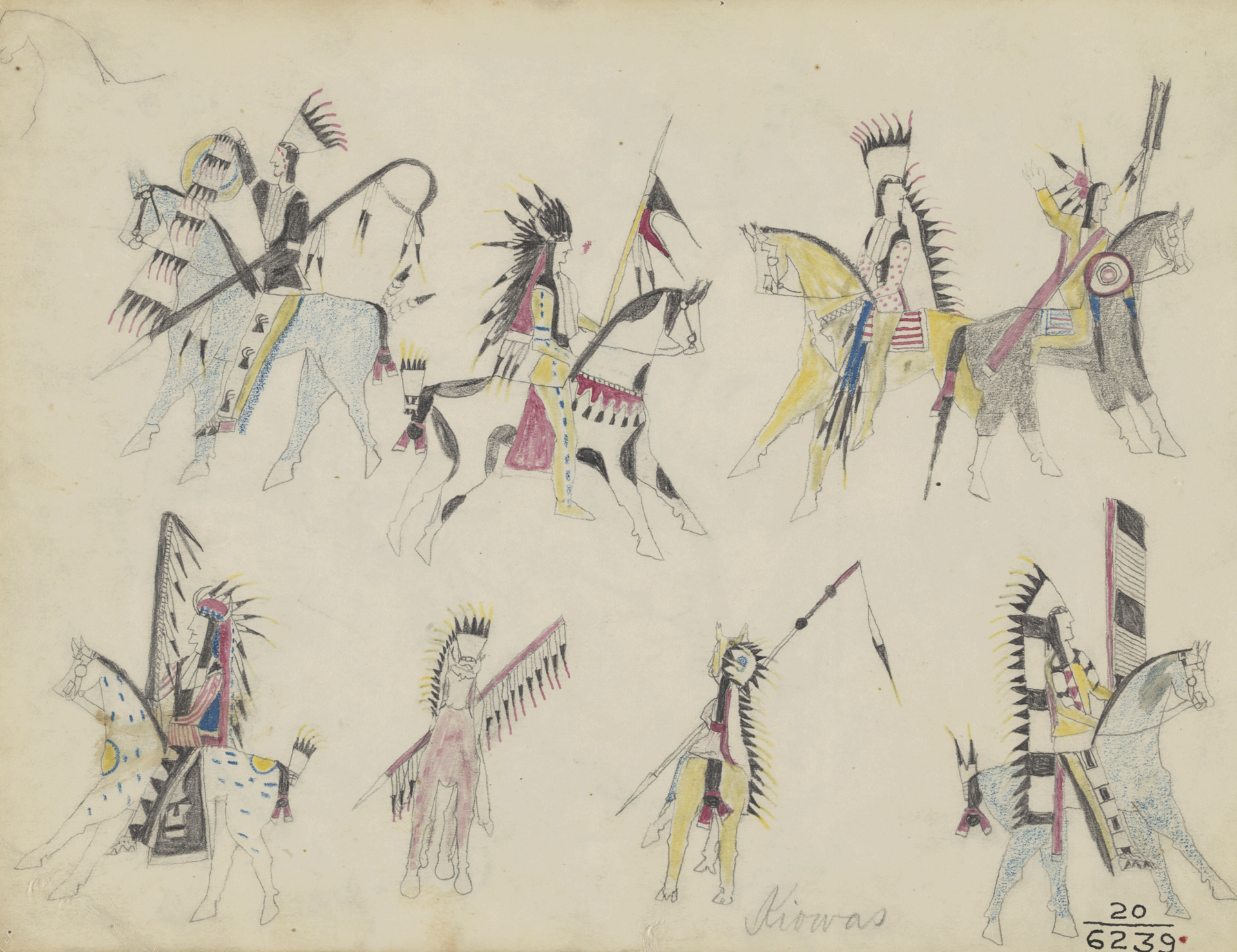

Vanessa: I’m a nosy old grandma. And years ago I bumped into a black and white photograph of this RISD cradleboard [Fig. 1], and it was ledger art [Fig. 2]! This Kiowa man is sitting on horseback! It was just extraordinary. Oh my goodness, I would love to ask the woman who made it, “Who is this man?” Because he did something important. And what greater way to remember it than to put it on a cradleboard, with new life coming. Maybe they promised that they were going to name this baby after this person. I don’t know, but that’s a possibility. This is a real war deed on the side of this cradle. You see the heart motif here, and a cross. Now I don’t know that they looked at that design like, “Oh, look, this is a heart.” I think they just saw it as beautiful. I’ve seen hearts on dispatch bags, on leggings, on the apron of a buckskin dress.

This technique she used is called a lazy stitch. You can actually see the rows where she put on the beads, and then it’s got little, almost like little lines between the beads. When you’re covering a large area, this is a good way to do it. And look at the way that the buckskin thongs are tied on for decoration. Usually they’ll put on tile beads or little hawk bells. It enhances your decoration and gives it that little bit of movement. Sometimes those are long enough that when the baby is in the board, they’ll actually be able to reach for them. I’ve seen cradleboard photos of my grandpa and my little sister where they’ve grabbed the end of that buckskin thong and stuck it in their mouth. It’s just a natural way for the baby to explore.

2

FIG. 2

Zotom (Biter / Zo-tom / Paul Caryl Zotom)

Kiowa, 1853–1913

Kiowas, 1875–1878

Drawing on paper with graphite,

colored pencil, and ink

26.3 19.8 cm.

National Museum of the American Indian,

Smithsonian Institution (20/6239)

Photo by NMAI Photo Services

All of my babies were in cradleboards. I made a different one for each child. A baby stays in their cradleboard as long as they want to. My sister actually took her first step right out of the cradle. Everybody just almost fell over, because she just started walking. That was my sister, though: brute force. “Let me out of here,” and away she went. Another story—they were videoing my granddaughter’s older sister playing basketball. You can hear everybody shouting and hollering, the mama saying, “Hustle, Alex! Hustle!” You see Alex running down the court. And then this baby sticks her head out of her cradleboard, takes a step out, looks back at the camera, and reaches for the bag that had snacks in it. She gets grapes and a bit of cheese, then she steps back and leans on the cradle. She’s just there on her side, eating apples and cheese. Then she reaches out and eats bananas. So I’ve got banana stains and it looks like red soda pop on the white wool on that cradleboard.

My son is my oldest, and he looks at things from what he thinks might be the Kiowa perspective. I was really proud of his graduating from high school. So many of our young people drop out. Nobody tells them, “Hey, you can do this.” Anyway, I asked him, what would you like for a graduation present? And he said, “I would love to have a red dance suit.” Now when I graduated from high school, this really wonderful Osage friend gave me eight or nine yards of red broadcloth and five sets of brand-new clothing, with all of the matching shoes and stockings and everything. At that time, I think, broadcloth sold for twenty-five dollars a yard. It was a lot of money. And now it’s maybe a hundred or even two hundred, if you can find it. They use it for cloth dresses and blankets and of course dance suits. So my son wanted this dance suit, and I’m poor. I’ve been poor my whole life, but it’s by choice that I have wanted to remain close to my people. And I’m too damn stubborn to leave.

Well, I got stuck on the broadcloth. I just always held onto it. I loved it, but I was terrified of it. What if I messed up? Because once you cut into it, you can’t back up and correct your mistakes. All of those years later, now my son wanted a red broadcloth dance suit. So I started digging through my piles of junk, and I’ll be darned if I didn’t find it. I prayed, I shut my eyes, and I started cutting. And I made him a broadcloth suit with a matching vest with aprons and a loincloth and a bag and everything. I gave it to him and god, he was happy. And on the front of his vest I put two horses that look like the horse on this cradleboard.

LISTEN: Vanessa Paukeigope Jennnings on Kiowa cradleboard construction

FIG. 3

Vanessa Jennings wearing one of her cradleboards, 1998

Photo by Carl Jennings

Our cradleboards are living beings [Fig. 3]. When you begin working on a cradleboard, the first thing you do is you go to the bois d’arc trees, and you pick out a tree.1 You don’t just take that tree, but that’s the one you talk to. And you tell him your purpose: “I’m here because there’s a little Kiowa coming along that Milky Way road, and we want to prepare a cradle for him.” And so you offer tobacco and you pray, and then you lay that tobacco down under that tree. And then you leave him, because that’s the leader. That’s the head man of those trees in that area. You tell him, “I won’t waste you.” The bois d’arc, it has really peculiar growth. There are going to be some knots or curves. And I don’t care how careful you are, how you’ve got it all planned out. There’s something with that tree, you’re not easily going to be able to make a board. It’s just the way that that wood lives.

After you cut your wood, you’re working with rawhide and the buckskin, stretching it out and getting it ready. And you’re talking to it, too: “I promise you that I will not waste any part of you. I will use every part.” Because this animal, the deer, they gave up their life. So you pray and you ask them to let you use them to make this the best way that you can. Then the fun begins, because that’s when you’re trying to figure out the design and how you want to put it on there. All Kiowa cradleboards are made in a specific way. To me, the inside is as pretty as the outside. But most people, it doesn’t matter to them. They just like the outside.

Now a man sees that tree and he thinks about the weapons he can make from it, but a woman will look at it and see how she can use it to take care of a life. The old Kiowas, they taught us everything. At one time, everything spoke Kiowa, even down to the weeds. That’s why when you go and you’re out in the country, you don’t need a chair. You simply sit down and that brings you close to Mother Earth and all other beings.

Anyway. You hear all about how brave men are and how they faced all kinds of dangers out on the frontier and on the prairie. But nobody ever talks about the amount of courage that it took for a woman to live out there under those extraordinary conditions. There used to be a bear here called a prairie grizzly, and it lived before our current American grizzly bear. It was bigger and more ferocious, and it took an extraordinary amount of courage for a man to face it down. But he would never even consider messing with the female, especially if she had cubs, because a female is just so ferocious. And that suits the way that Kiowa women were, because they were protective of their young. Of course they couldn’t fight smallpox, they couldn’t fight any kind of fevers, but they would really work hard to use prayers to get around that, to save their child. In the end, the women’s grief is so strong. They’ve loved so hard that, at the death of a child, they would actually cut off their fingers in mourning. That’s how powerful the depth of their love is. Yes.

Women will cut their hair really short in mourning, too. There’ve been so many deaths in the pandemic, this group of young women recently took it on themselves and said, “We should have a Scalp Dance, and that would maybe help chase the pandemic away from Kiowa country.” My daughter looked around said, “Mama, there’re so many women that I remember that had long hair. And now their hair is cut.” And this question came up: “I cut my hair when I lost my brother, my dad, my uncle. And now I’ve had another death. Am I required to cut my hair again?” That is a logical question, but I said, “You've already cut your hair. There’s no need to cut it again.”

At one time, Kiowas had a really structured way of life. The traditional Kiowas, they urge personal integrity. They urge personal courage. I mean, these were mandatory. And so it was possible for a warrior to come through the ranks, to come to the top, the elite. But just as easy, a man could fall. The person who’s depicted on this cradleboard, he’s at the top. And the woman who is making this cradleboard? She isn’t just good. She is the best. For most anthropologists, this would be considered ledger art, and they would assume that style is only done by men. But this is a woman working on this cradleboard.

In the modern world, they talk about a glass ceiling. Well, in the Kiowa world, there is like a glass wall. Actually, it’s not even glass. It’s completely invisible, but you know that there is a boundary line. Men cannot skip over that and come into a woman’s world, and a woman cannot step into a man’s world. But you believe me: there is the power of pillow talk. You can force your opinion but that man can still go out there and look strong and powerful. He can put it in his words and say, “I thought about this, and I think it would be best if—” but it’s actually the viewpoint of the woman. We’ve all laughed about that—“Shoot, you see how I got a hold of him last night and swept him around?” Family is very important to us, family history is important. And you have to remember that we didn’t have photographs. But we have these magnificent women. It wasn’t unusual for Kiowas to have several wives. Especially a wealthy man. And usually the first wife, that’s the dominant wife. She calls all the shots in the camp. So, more than likely, she would be the one to be making a cradleboard like this.

It is your job as a Kiowa wife to honor your husband. When I Scalp Dance, for instance. My husband was in the CAB in the United States Army.2 It’s the same cavalry that was commanded by General Custer. I put that emblem on my dress, and I also beaded it on my grandson’s cradleboard. I’m not honoring Custer, I’m honoring my husband. Right there, that’s telling you that this child, this baby, comes from a warrior family that needs to be respected. My grandfather, he served.3 He joined in World War I. They had heard that after served, when you came back you would be made an American citizen. They were looking at it as a way to become an American citizen. Well, it worked for everybody else, but not for them.4

You say this cradleboard was owned by James Randlett.5 Someone said maybe it was made for sale or is unfinished, but I don’t think so. You can see where the beadwork ends, and then you see the buckskin. I do that on my own cradleboards, and it’s got nothing to do with being unfinished. Every cradleboard, you go into it like you’re dealing with a living connection to that unborn baby. Cradleboards were meant to be used, especially during that time. If the baby didn’t live, it wasn’t unusual for the cradleboard to be the coffin for the baby. So it makes sense why there aren’t so many older ones, or in this style, because quite a few were buried with the babies.

I mean, life isn’t easy, which is another thing about cradleboards. That’s the beginning of them, that old woman praying and saying, “Life is hard. It’s incredibly hard.” But making a cradleboard ties all of these animals to this child. They’re there to support him and to help him. And then the father of the baby and the mother of the baby, their spirit is tied to it. The most important one is the grandfather. And of course the one who is going to have an effect on you for your entire life is your grandmother. Those people, those spirits, are all tied to that cradleboard. And you, taking care of this cradleboard now in the museum, you can offer prayers that they’re at rest. You can tell this board, “I’m here because I’m one of the helpers.” And that’s what you are. You’re helpers.

4

5

FIG. 4

Vanessa Paukeigope Jennings

Cradleboard, 1998

Wood (plant material), glass beads, cotton, thread, hide, and brass

134 33.5 cm. (52 3/4 13 3/16 in.)

Haffenreffer Special Fund, Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, Brown University

Courtesy of the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, Brown University

FIG. 5

Vanessa (right) and her sister, Stevetta Denise Mopope (in cradleboard), ca. 1955.

Photo courtesy of Vanessa Jennings

I made my sister the cradleboard that I sold up there to the Haffenreffer Museum [Fig. 4]. When a cradle is finished, you invite your relatives, and you put that cradleboard in front of everyone and they touch it and they pray. They rub their hands all over the front, the side, the back, and the bottom. It’s really important. And the last one who touched that board was my sister [Fig. 5]. She died of breast cancer soon after that.

“If you give a gift and it hurts, it’s the right thing to do.” My grandmother said that.6 This is an old custom, and it still happens. And believe me, I’ve handed over some things when I was practically in tears, hanging on to it, as the new owner said, “Oh, thank you very much.” So I can see how Randlett might have said to this elite woman about this cradleboard, “Oh, that’s pretty,” and she just took the baby right out and gave the cradleboard to him. By doing that she would be saying, “Here, my friend. Think kindly of us. Remember us in a good way.”

It’s an old way, but some of the young people today, they’re not taught. At a gathering, we were waiting for the dance to start. And a young girl told this lady that was sitting with me, “Oh, your earrings are just beautiful.” And everybody turned and looked at her. And she asks the young girl, “Who are your folks?” And the young girl didn’t know what she was talking about. You always identify yourself to an elder. This is so they can figure out where you fit into the dynamics of Kiowa society. And this girl had no idea why this old lady was asking her who her family was. So the lady simply told her, “Thank you, dear,” and the little girl went off. When the girl got out of earshot, she said, “I’m Kiowa, but I’m not stupid. She wouldn’t have appreciated what I was doing.” And I got to thinking about it and I said, “You know what? She’s right.” Yes, I am really careful when I tell somebody, “Oh, that’s pretty” or “Oh, that’s nice.”

At the Haffenreffer Museum, they have a whole collection of old Kiowa cradleboards, and that’s because a young doctor was here and when he delivered children, out of gratitude—out of respect—they turned around and they gave him a cradle. There again, that shows, “This is a powerful man, and he helped us.” I don’t know about Randlett. There were many that came here that were corrupt. The agent and superintendent had power. They oversaw rations and came after children to send to the Indian schools. Some poor old grandma who had an important son-in-law, she could ask him to go and ask for mercy from the superintendent. You know, she’s in poor health and this grandchild helps her. And so they might not drag that grandchild off to boarding school.

6

FIG. 6

Ka’igwu (Kiowa) Cradleboard,

ca. 1900

Wood, leather, beadwork,

and brass tacks

Length: 111.1 cm. (43 3/4 in.)

Museum Works of Art Fund 44.610

The yellow pigment that’s on the buckskin [Fig. 6] is yellow ochre that comes from the earth. Amarillo is about four hours from me and then about another thirty or forty minutes south is a place called Canyon, Texas. And that’s really what it is—a canyon. Down at the bottom, that’s where the Kiowas hid when they ran away from the reservation.7 So the agents called the army, and the army went looking for them. They got down into that canyon, and there were some people who said, “If we stay here, we’re safe.” Others said, “Well, if we go north, we could get away from the agent and the soldiers.” So while they’re arguing, General Mackenzie found a way down and they killed all of the horses and all of the mules and they took all of the teepees—everything—and burned them so that people just ended up with the clothes on their backs. Some of these men were powerful and respected warriors. This one man had a young wife that he favored, and he tells her, “I’m going to put you on this horse. You take the baby. Don’t look back.” And then he slaps the horse. Well, that horse is so strong. This is his horse that he uses for a war parties and war journeys. The only one that messes with it is the owner. Same way with the buffalo horses. And so he slaps the rump of this animal and it takes off. And the young girl is riding away and all of a sudden she loses the child. Well, she manages to turn that horse around and she bends over. And this is what’s always impressed me: she bends over, and at a gallop—a full gallop—she reaches down and she picks the baby up. It’s a toddler, too big for a cradleboard. And when she pulls the baby up, a soldier shoots the horse and kills it. So the soldiers grab her and the baby.

Then they marched all the Kiowas back to Oklahoma. This is the biggest insult for a horse culture like the Kiowas. And it was raining. You know when you leave your hand in the water and your fingertips pucker? Well, they called that the Year of the Wrinkled Handshakes, because they walked and it rained and their skin puckered. And that’s where I go to get this yellow—this canyon—because that’s the place that we went to. It represents an important event to the Kiowas. That yellow ochre, that’s what I use, but I never put it on anything for sale. I use it on things that we’re going to keep. It’s just a very beautiful color. Okay, my husband wants to ask you a question.

Vanessa and Carl Jennings.

Photo by Lester Harragarra

Carl: It looks to me like this is a cover that was taken off the boards after it was damaged and put on new boards. The hide under the cover, under the beadwork, is different than the hide that is visible. And the bottom piece that is sewed on at the beadwork line should be one piece of hide.

The beadwork should be about five inches longer. It looks short to me. So I’m supposing that the bottom part of the cradle was damaged with water or whatever, and they’ve cut it short and they’ve put this hide that’s normally a part of the beadwork hide. They patched it on. That piece of hide on the bottom that’s painted yellow and no beadwork on it is much longer than it would be normally.

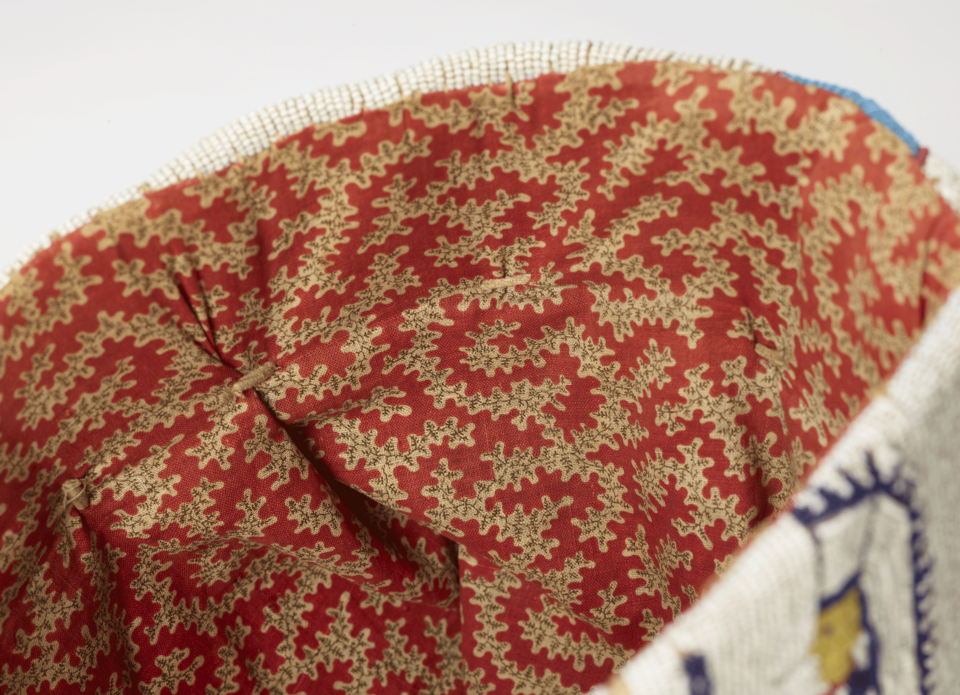

When it was sewn on, it was sewn on and then turn turned in, and there’s a fold in the hide that wouldn’t normally be there. Usually if you’re going to do a cover on canvas, you’ll sew a piece of hide on that and cover that seam. And they have not done that—cover the seam with beadwork. I’m saying it’s an older beadwork, and they’ve repaired it at some point. Of all the cradleboards I’ve seen, only three that have this kind of pictorial beadwork on it. Ninety-nine percent of them are of geometric designs and floral designs. This hide looks like it was fairly new in the early 1900s, but the hide under the beadwork is darker and, I would say, at least twenty years older than the repairs. Most cradleboards are much more detailed. Their designs aren’t this large. It’s just, this beadwork looks clunky to me. And the calico of that cotton also looks to me like it’s older than 1900.

I can’t see anything wrong with the boards. They’re Indian-made and bois d’arc will turn this color. It could be walnut, but I don’t think so. You can check the boards: if it’s a harder wood, it’s bois d’arc. Walnut is softer. Also, if you scratch somewhere on the back, the inside will still be yellow if it’s bois d’arc.

And the hide strings that it’s sewed to the board with—if they’re repurposed or repaired, they took the boards off the cradle. They’d take them off and store the beadwork, and then two, three, four years later, when they have a new baby, they’d make new boards and put it back on. So maybe that has to do with its construction. But definitely the beadwork to me is short.

And this construction of the hood, it’s not the way we make them, the way that she learned to make them. And the way that it looks like a baseball cap, kind of sticks out and has a definite curve to the body. I’ve seen them made like that. There’s nothing to say there that it’s older or even younger, but it’s not the way we make them. She’s got a cousin that makes small boards and they have this construction to them and I can’t say where he learned to do that. I don’t know. It’s interesting that in one family they’d make them different ways. But he had a misspent youth, and I think that had something to do with it.

Photos by Lester Harragarra.

Vanessa: Can you tell we specialize in old gossip? But we are two independent human beings. We have different ideas. And I’ve always been smitten with this cradleboard. I’m a nosy, nosy old woman. Here in Oklahoma, down in the—don’t laugh—in the livestock building, they had this big powwow. They had these vendors set up, and everybody’s walking around looking. This non-Indian had a bunch of old photographs, and here was a picture of this cradleboard. It was so striking, I asked him, I said, “How much is this?” And he said, “Five dollars.” It was so beautiful. I could afford five dollars so I went ahead and bought it and I brought it home. I would pull this photo out and look at it, and I would wonder, “Who were you? Who were you?” I truly believe that there are spirits, and obviously that one wanted to be loved and appreciated, and nobody was looking at it. But I found it, and I brought it home.

I have no idea how this board ended up in Rhode Island, but to me the most powerful of all Kiowa art is the cradleboard. Oh—Carl has another question about something.

Carl: Hey, this is beaded on canvas, isn’t it? Okay, that’s what I thought. They had canvas in the 1850s as a trade item. It was expensive, and it got cheaper as time went along. So that doesn't really say anything about the age, because before the wars they had canvas, but that could speak to how it got damaged.

Also, it looks like the beadwork design at the top edge is folded in. So the original was perhaps bigger when they put it on new boards, and a new rawhide hide for the inside, that was made smaller, so the beadwork folded over. There’s nothing to say that the original didn’t fold over, too. I don’t know. But that’s something to look into. You might look under the red fabric on the inside where it’s sewed down. Look under that seam and see if there’s beadwork that they covered up. Anyway. Here’s Vanessa.

Vanessa: Before you hang up: Kiowas are adaptive. They see something and think, “Hey, you know that’ll make this or that.” And this is a good example. Back in the sixties, there was this woman, Winifred Paddlety. She made and entered a beaded cradleboard at the American Indian Exposition they have. They would give just a little blue ribbon for first prize—there was no money or anything like at Indian Market. But all these old ladies, they’re talking. And I got big ears, too, besides being nosy. I learned to listen a long time ago at my grandma's feet, picking up beads when she couldn’t get down on her hands and knees anymore. And you never waste beads when you accidentally drop them on the floor. So I’m down there on my knees, saying, “And then what?” And my grandma thumped me on the head. “You’re not supposed to be taking part over here. You’re supposed to be picking up the beads.” When you’re around adults, you can hear as long as you’re quiet.

Anyway, these women were scandalized that she had used velvet for her cradleboard, because at that time I think velvet was like seven dollars a yard, and they just couldn’t believe. “You know how expensive that is?” and “It’s so difficult to work with.” They were just going on and on, and she had the audacity to make a cradleboard with it. And now, years later, that cradleboard belongs to her great-grandson. But age will wear things away over the years. Like everything else.

Anyway. You ladies see, I’m full of stories. You should hear more stories about the power of women. But that’s for another time.

Vanessa Jennings (center) at her Black Leggings camp with (from left) her granddaughters, Elizabeth Morgan and Winter Morgan; her aunt, Donna Jean Mopope Tsatoke; and her daughter, Summer Morgan, ca. 2011.

Photo courtesy of Vanessa Jennings

- Maclura pomifera; also commonly known as the osage orange.

- Combat Aviation Brigade.

- Jennings’s grandfather, Stephen Mopope (1898–1974), was a musician, dancer, and member of a group of celebrated artists known as the Kiowa Six.

- Kiowa tribal members and the citizens of other Native nations would not become US citizens until 1924, with the Indian Citizenship Act

- Colonel James F. Randlett (1832–1915) served in the US Army beginning in the Civil War and later worked for the federal government as an Indian agent.

- Jennings’s grandmother was Nellie Jeanette Berry Mopope (1904–1970), a Plains Apache traditional artist.

- The Red River War of 1874–1875 was the last major conflict between the US Army and Southern Plains tribes. Kiowa, Southern Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Comanche leaders were imprisoned and tribal members were forcibly relocated to reservations.

Cite this article as

Chicago Style

MLA Style

Shareable Link

Copy this page's URL to your clipboard.