OBJECT LESSON

To You

Stephen Truax

1

FIG. 1

Louis Fratino

American, b. 1993

View of Monte Cristo, 2020

Oil on canvas

91.4 × 50.8 cm. (36 × 20 in.)

Promised Gift of Les Christoffel

and Paul Greene

Artwork © Louis Fratino, courtesy of

Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

I wanted to be sure to reach you,1

— Frank O’Hara

Did the artist sleep all night with the window open and wake to this framed view? Palm and coniferous trees reach into the early morning sun. In the distance, a pink horizon. Is it a body of water illuminated against the sky? The glass windowpane on the far right edge of the painting reflects a spectrum of colors—gold, crimson, gray, lime, azure.

A pair of jean shorts lies on the sill, as if left there to dry overnight. A red drawing pencil lies across them, perhaps taken out of the young painter’s pocket at the end of the day, a symbol of his earnest work. Wedged under the lattice, propping it open, is a thick book—Frank O’Hara’s Selected Poems.

The cover is identifiable by the poet’s name, written in lavender paint, and his portrait, with that unmistakable ear, in Fratino’s view a delicate nautilus shell curled at the base of his skull. Another young gay man attempting to capture his experience as a young gay man, frustrated by love and sex (our shared, inherited history). Perhaps Fratino read last night beside the open window, “[A]round my fathomless arms, I am unable / to understand the forms of my vanity.” In this book—another symbol, the legacy he inherits as a gay man, as a queer artist—he might underline certain passages, or make dutiful notes in the margins.2 Or perhaps the young artist imagined (as many of us have) that O’Hara was just as much in love, and suffering just as much as he was: “To / you I offer my hull and the tattered cordage / of my will.”3

Could he smell the sea air? “Salt and negative ions turned up by the surf,”4 swept in from the ocean. Did the humidity dampen his clothes and his bedsheets in the night? Louis Fratino’s View of Monte Cristo [Fig. 1] bristles with erotic energy. The suggestion of the artist undressing and standing in front of the window in the cool night air implies that we, the viewer, are now standing in that same space with him (or where he was only recently), an encounter charged with sexual possibility.

It is rare that a painter can capture so completely not just his own life but a whole lifestyle: being an attractive gay man in Brooklyn today looks idyllic. Throughout the twenty-seven-year-old artist’s third solo exhibition in New York, Morning, held in 2020 at Sikkema Jenkins & Co., couples stretched out in languor, still in bed as the sun streamed past the houseplants. But View of Monte Cristo was an unexpected punctuation to the exhibition, and one of the few paintings in the show that didn’t have anyone in it. While neighboring paintings provided a romantic context, this work seemed to have more to do with the artist’s confrontation with his life opening up before him than the description of being together with another man. View of Monte Cristo could be the overwhelming, limitless opportunity of youth. To look out the window onto an unfamiliar view—the view is not just new to you, but new to everyone. Every new image explodes with potential meaning! The excitement to greet the day is a palpable tingling in the small of your back. It is not just this vista, but the boundaryless horizon of possibility.

And it’s here where queer figurative painting points not just to solipsism and identity politics but to something that resembles Transcendentalist philosophy. The nineteenth-century study of universal belonging and connectedness can be linked to our twenty-first-century conception of queerness. For all its radical political implications, finally, queerness now can share that expansive narrative. It grows to include and touch more constituents than its original scope.

2

3

FIG. 2

Installation view,

Any distance between us,

RISD Museum, 2021

FIG. 3

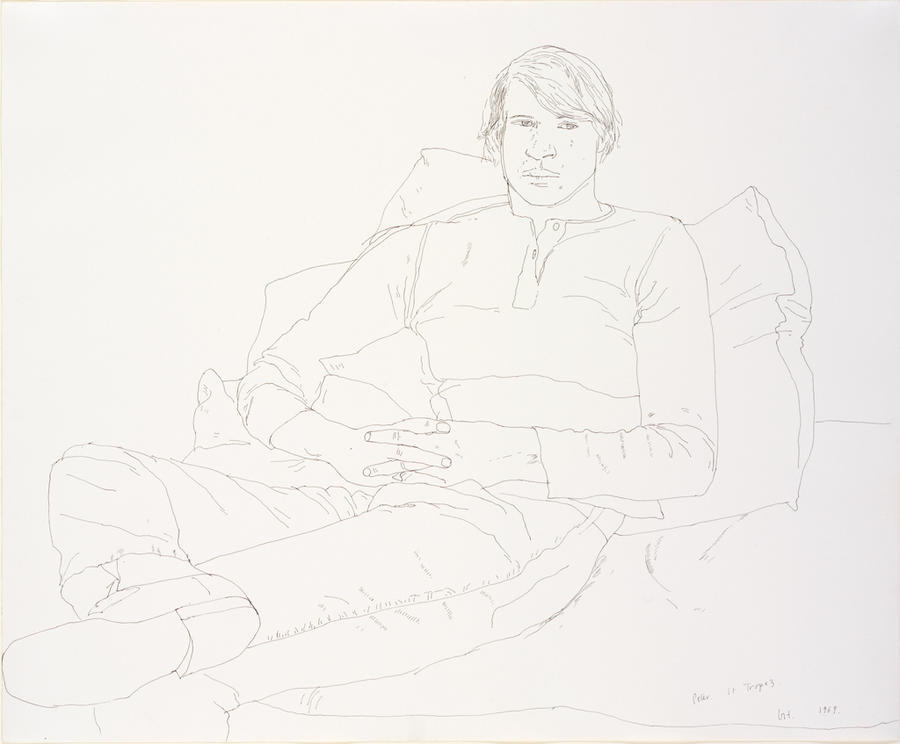

David Hockney

British, b. 1937

Peter Resting with Clothes on, St. Tropez, 1969

Pen and ink on paper

36.8 × 44.4 cm. (14 × 17 in.)

Gift of Richard Brown Baker 1996.11.20

© David Hockney

It is precisely this expansion of the queer frame found in Fratino’s View of Monte Cristo that generated a collaborative curatorial project between Dominic Molon, the Richard Brown Baker Curator of Contemporary Art at the RISD Museum, and myself. The result, Any distance between us [Fig. 2], is an exhibition focused on radical queer art made over the past three quarters of a century, and focused also on adjacent practices that use figurative and conceptual methodologies associated with that movement by artists of color.5 Artists TM Davy, Salman Toor, and Nicole Eisenman are old enough to be examples for Louis Fratino. Others, including Patrick Angus, Alvin Baltrop, Hugh Steers, Peter Hujar, and David Wojnarowicz—all of whom died of AIDS-related illnesses—emerge from a time in which one could scarcely imagine Fratino’s fearless and unencumbered painting project. Generations of artists who came before us are essential to the celebration of life we find in Fratino’s work. We have the opportunity here to trace this rough history of queer art and its rich lineage of majority-queer-identified artists.

In the wake of the AIDS crisis in the US in the 1980s and ’90s, younger artists were cut off from queer historical predecessors. Regardless, we find that queer artists throughout the twentieth century also turned inward to their lived experience and personal identity to make powerful political gestures, similar to what we see in contemporary art today. This exhibition strives to articulate this important and sometimes overlooked artistic movement. It visualizes the essential art-historical through line for these works, which seem both humble and unassuming, considering their modest scale and use of traditional materials. Their accessibility beyond the queer community reaches into broader contexts.

In David Hockney’s Peter Resting with Clothes on, St. Tropez [Fig. 3], the artist looks at this handsome young man, his lifelong lover, Peter Schlesinger, with an unmistakable affection, an almost completely unbroken line tracing the contours of his subject’s face with care. Peter’s expression is so calm as he gazes back, unafraid. Is he smiling a little?

One can intuitively sense even then the homoerotic undercurrent of the portrait. And the curious addition to the title, “with clothes on,” is so suggestive of other activities that might have distracted the artist, who was just thirty-two at the time. Not even a whisper of the coming plague less than a decade out. Notice how each digit of the subject’s folded hands is articulated, but even more, so how fearlessly Hockney revealed his attraction to this man—not only to Peter, his subject, but to us, the viewer. Hockney is a clear reference point for Fratino, and, like O’Hara, represents a previous generation of gay men who made their love and sex lives an unavoidable aspect of their public work.

4

FIG. 4

Patrick Angus

American, 1953–1992

Untitled, 1980s

Crayon on paper

27.9 × 35.6 cm. (11 × 14 in.)

Courtesy of Charles Renfro

© The Estate of Patrick Angus

It would have been a drawing like Hockney’s that inspired Patrick Angus to sketch portraits of his own friends and lovers asleep in his bed, or reading on his couch, nearly thirty years before Fratino did. Three untitled examples [Fig. 4] made by Angus in the 1980s are on view in this exhibition. These drawings offer a respite from dangerous New York; beautiful boys were safe and comfortable in the artist’s apartment. Unlike Hockney’s arcadian images of men swimming naked in Los Angeles pools and luxuriating in expensive hotel rooms, Angus is best known for his images of Times Square porn theaters in New York City in the 1980s. These paintings capture the terrifying desire of men who risked their lives to cruise for sex, and are especially charged because the artist himself succumbed to AIDS in 1992, at the age of thirty-nine.

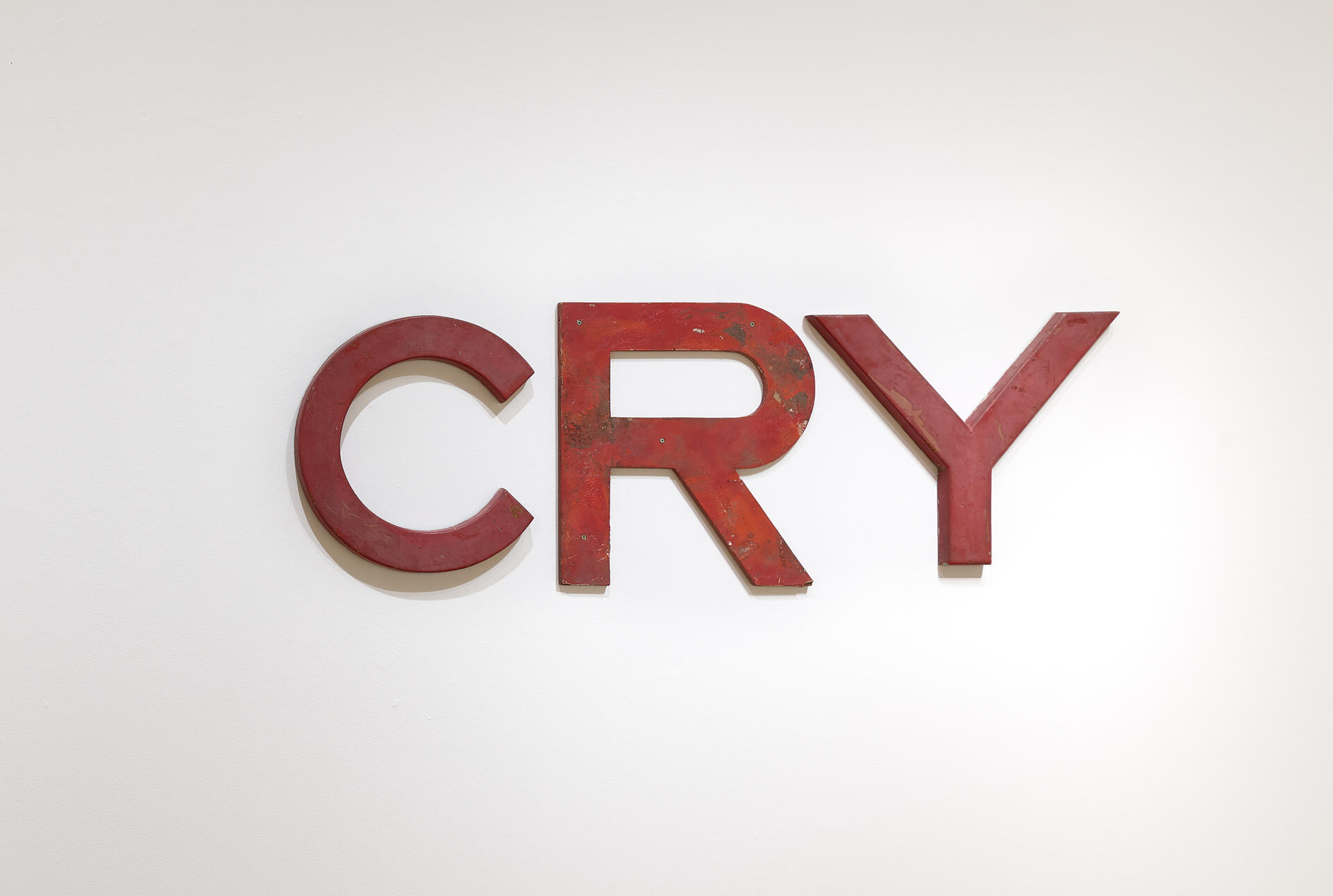

It was the rusted sign letters from these same theaters that Jack Pierson found and collected in his Times Square studio. He rearranged the letters into phrases, one of which became a word sculpture that spells out Cry [Fig. 5], also on view in Any distance between us. Like Angus and Hockney before him, Pierson turned to graphite drawing during the early, urgent years of his practice—here he was thirty-one. His delicate 1991 pencil rendering of a twin bed next to an open window is overwritten by faltering and heavily edited text that finally spells out:

Do you ever

even for a second

wake up

and think

it’s me

next to you?

As confident and beautiful as Hockney’s 1969 drawing is, Pierson’s by comparison is jittery and stilted, hard-won through much erasure and reworking, like pentimenti. The empty bed is unmade and the curtain is nothing more than a transparent bit of fabric tacked up across the window. It is an image that captures the anxiety and frustration of unrequited love, or perhaps of love lost—all those painful, burning experiments we must suffer in order to learn the meaning of true intimacy, of being truly vulnerable. So often these fleeting romances of our youth take place in a theater of poverty, where the lack of material comforts and perhaps even our actual physical hunger mirrors the longing for our absent lover. The empty bed has been slept in, the pillow imprinted where his head rested. Perhaps it still smells like him. Pierson’s image lingers with us. Even if the drawing is just a send-up, a theatrical prop, it is immediately recognizable as familiar suffering. Haven’t we all been there, alone in a room that used to accommodate two? It is heartening to see someone else’s description of their suffering match our own, offering us a sympathetic link through time.

5

6

FIG. 5

Jack Pierson

American, b. 1960

Cry, 2009

Metal, wood, and paint

50.8 × 54.9 × 2.5 cm. (20 × 61 × 1 in. )

Helen M. Danforth Acquisition Fund 2018.37

© Jack Pierson

FIG. 6

Elle Pérez

American, b. 1989

Mae at Riis, 2020

Archival pigment print

76 × 50.6 cm. (29 15/16 × 19 15/16 in.)

Museum purchase: gift of the RISD Museum Board of Governors, Fine Arts Committee members, friends, and colleagues in honor of John W. Smith, Museum Director, 2011–2020

© Elle Pérez, image courtesy of the artist and 47 Canal, New York

Drawing on their unconventional friendship, Elle Pérez captured Aurora Mattia (identified in the title as Mae) in a photograph taken on a cloudy day at Jacob Riis Beach [Fig. 6], celebrated as a community beach for queer, trans, and people of color, in New York City, which has been a special site of queer lifestyle since the 1940s. No one else was on the beach that day. Standing in the freezing-cold surf in blue jeans and a white lace bra, Mattia is wrapped in a gossamer shirt the same color as the sand, her hair whipping in the wind, staring back at Pérez, the photographer—and at us, the viewer—not with defiance but a questioning expression. Do you see me? Will they see me as you do?

Pérez invited Mattia to contribute writings from their upcoming book The Fifth Wound to accompany their photograph in this exhibition (as well as in a 2020 group show at the Renaissance Society in Chicago), permanently linking their works together. Mattia wrote, “Look, if you have seen my photographs, then you know about my surgeries, I don’t need to tell you. And if you haven’t seen my photographs, the truth is I don’t know you.”6 Linking these two projects with Mattia’s relationship to gender identity confronts the viewer with Mattia’s physical allure, shoulder bared to the camera. Yet despite this connection to the photographer, there seems to be a certain remoteness in Mattia’s gaze. We participate in this moment of vulnerability as witnesses to the empathy and care of a private exchange between intimate friends.

Pérez’s photograph offers a generous view into trans life. Here we see the photographic legacy of the radical vulnerability of Nan Goldin and Peter Hujar, whose work is inextricably linked to the queer liberation movement. Goldin’s portrait of her friend, Vivienne in the Green Dress, NYC, and Hujar’s self-portrait, in which his own gaze is also burning yet remote, are both on view in the exhibition. The democratic unfolding of queer liberation continuously expands and grows to include more people. While far from a perfect unity, this opening up of the LGBTQIA+ community becomes a program for more work.

7

FIG. 7

TM Davy

American, b. 1980

Here and There, 2020–2021

Oil on panel

81.3 × 66 cm. (32 × 26 in.)

Courtesy of the artist and

Van Doren Waxter

© TM Davy

TM Davy turns his attention to a sweet moment between two male friends in the painting Here and There [Fig. 7]. One in a black hoodie, the other naked from the waist up, they look up at the evening sky on Fire Island. An infinite variety of colors opens up before them, as if intended for them. His hand gently resting on the other’s back, one man looks as his friend points out the first evening star—or is it a planet?—next to the full moon. The artist was there that night, standing right behind them, looking up at the same sky, the same moon, the ocean and the tide. What experience could be more available to share than facing together toward the same celestial event?

There on the beach, where the sky is so much bigger than it ever seems in the city, both men stand barefoot in the cold sand at dusk. The shore is a precipice before the vastness of space. The water reflects the pink sky and we stand with them, in awe at the transcendental wonder of our world. Jupiter and Venus were both visible almost every night last summer. Like Fratino looking out his window with us, Davy’s figures look out together to the horizon with us. This composition assumes our presence and participation in that moment with the artist, or even as the artist.

“What relationship is safe enough to make it the subject of one’s work?” I asked in a review of Nicole Eisenman’s 2016 exhibition at Anton Kern in New York.7 In 2017, this inquiry expanded into an essay, commissioned by Artsy, based on a series of studio visits and interviews I conducted with a group of seven queer-identified painters, titled “Why Young Queer Artists Are Trading Anguish for Joy,” which was one of the first texts on recent queer figurative painting. Louis Fratino, Sholem Krishtalka, Doron Langberg, and TM Davy were all featured in the essay, as well as in the subsequent RISD Museum exhibition.

8

Installation view, Any distance between us, RISD Museum, 2021

FIG. 8

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

American, b. Cuba; 1957–1996

“Untitled” (Couple), 1993

Light bulbs, porcelain light sockets,

and electrical cords

Two parts; overall dimensions vary with installation

Installation view: Any distance between us,

Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design (RISD),

Providence, RI.

July 17, 2021–March 13, 2022. Curated by

Dominic Molon and Stephen Truax

© Felix Gonzalez-Torres

Courtesy of The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

I wrote: “Artists are turning to figurative painting, focusing their work on personal experiences and intimate domestic environments. Their work has a direct relationship to their own queer lives, which they present without fear of cultural, social, or legal repercussions.”8 Tender and without irony, their paintings verge on the sentimental and are unapologetically beautiful. These young artists had taken the agency to choose subjects that had meaning in their own lives—their sexual desire, their falling in love, their heartbreak, their chosen family—in a way that I had not previously encountered in my own lifetime.

The essay focused on the history and legacy of queer art over the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and it became essential to explore those strong historical roots in an exhibition. My 2018 curatorial project Intimacy, which was presented at Yossi Milo Gallery in New York, crystallized this group and how their ongoing practices relate to previous generations of queer aritsts, including Patrick Angus, Hugh Steers, Paul Cadmus, Robert Mapplethorpe, Peter Hujar, and David Wojnarowicz.9 That show, like this one, celebrated queer artists active today in context with a rough historical lineage of queer art from which their work emerged. Any distance between us grew out of those efforts and expanded to more poetically encompass relationships and closeness across contemporary contexts.

Generations of queer artists are separated by societal and political events of extraordinary magnitude that have taken place from the late 1960s to the present, therefore the links that we can draw between these artists are often more emotionally associative than strictly art historical. One such poetic interpretation is that Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s 1993 "Untitled" (Couple) [Fig. 8] is an elegy to true love lost to AIDS. Two light strings, forever gently entwined, descend from the ceiling to pool together on the floor; Gonzalez-Torres's radical openness and material restraint leave the viewer's experience open to many more possible meanings and interpretations. Incandescent light is cast across the entire exhibition and is reflected back on the surfaces of the many surrounding artworks. We don’t see the same kind of terror or tragedy in Fratino, Davy, or Pérez, but all of these artists look back to other young queer artists and poets, like O’Hara, and especially Whitman, who wrote in 1856, at age thirty-seven, in the second edition of Leaves of Grass, “Whoever you are, now I place my hand upon you, that you be my poem.”

Both Whitman’s and O’Hara’s poetry carries the specificity of lived experience that transcends a particular milieu and speaks across the time that separates us. Whitman wrote, “Just as you stand and lean on the rail, yet hurry with the swift current, I stood yet was hurried.” He continued: “I consider’d long and seriously of you before you were born.”

What young artists today offer their own generation is the celebration of queer life, but what they offer to the previous generation, the one that survived aids, is the joyous, unrepentant ability to say it at all. Unencumbered by revolutions, by plague, by systematic oppression, their work is liberated to be as beautiful, as tender, as revelatory as they wish it to be, as it could ever be. And this is their triumph: that we were able to live to see it. Whitman wrote:

Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged,

Missing me one place search another,

I stop somewhere waiting for you.12

Tony Kushner adapted that line in 1991 in his play Angels in America. The Angel says to Prior, a young man living with AIDS:

Hiding from me one place, you’ll find me in another.

I-I-I-I stop down the road waiting for you.13

- Frank O’Hara, “To the Harbormaster,” from Meditations in an Emergency, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/42661/to-the-harbormaster. Copyright © 1957 Frank O’Hara. Reprinted with the permission of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

- O’Hara had an outsized impact on modern and contemporary art; he championed the work of the Abstract Expressionists and was intimately involved with queer artists such as Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg while he served as a curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

- O’Hara, “To the Harbormaster,” from Meditations in an Emergency.

- “If you’re lucky in life, a place, or two, will be offered to you. . . . The air will taste of ocean, negative ions churned up by the surf” writes Paul Lisicky in Later: My Life at the Edge of the World, in a passage titled “Utopia” (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2020).

- Any distance between us, curated by Stephen Truax and Dominic Molon, on view July 17, 2021–March 13, 2022 at the RISD Museum of Art, Providence, RI.

- Aurora Mattia, “Lipstick Traces,” from The Fifth Wound, forthcoming from Nightboat Books, 2022.

- Stephen Truax, “Nicole Eisenman,” Brooklyn Rail, July/August 2016, https://brooklynrail.org/2016/07/artseen/nicole-eisenman-2016.

- Stephen Truax, “Why Young Queer Artists Are Trading Anguish for Joy,” Artsy, November 7, 2017, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-young-queer-artists-tradi….

- “Patrick Angus and Hugh Steers, both active in New York in the 1980s–early 90s, dealt with overtly queer, domestic imagery; both succumbed to AIDS-related illness. . . . In Steers' painting, Two Men and a Woman, 1992, a woman washes a naked man suffering from AIDS while his partner looks on, capturing the agony of watching a loved one pass away. Both painters, though underrepresented during their short lifetimes, made work that became instrumental in queer figurative painting today.” Exhibition text for Intimacy, curated by Stephen Truax, on view June 28–August 24, 2018 at Yossi Milo Gallery, New York.

- Walt Whitman, “To You,” from Leaves of Grass (1856 and subsequent editions), https://whitmanarchive.org/published/LG/1891/poems/100.

- Walt Whitman, “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” from Leaves of Grass (1856 and subsequent editions), https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45470/crossing-brooklyn-ferry.

- Walt Whitman, “Song of Myself 52,” from Leaves of Grass (1856 and subsequent editions), https://poets.org/poem/song-myself-52.

- Tony Kushner, Scene 2 of Act 2: Perestroika, Angels in America.

Cite this article as

Chicago Style

MLA Style

Shareable Link

Copy this page's URL to your clipboard.