OBJECT LESSON

“Deaf Gain”

in the Cabaret

Toulouse-Lautrec’s Yvette Guilbert Taking a Curtain Call

Alexandra Courtois de Viçose

1

FIG. 1

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

French, 1864–1901

Yvette Guilbert Taking a Curtain Call, 1894

Watercolor, crayon, and oil paint on

tracing paper mounted to cardboard

41.7 × 24.5 cm. (16 7/16 × 9 11/16 in.)

Gift of Mrs. Murray S. Danforth 35.540

Probing outlines and washes of color bring into being famed cabaret performer Yvette Guilbert as she salutes her audience [Fig. 1]. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s 1894 preparatory study, Yvette Guilbert Taking a Curtain Call, challenges portraiture as a genre claiming to register a person’s likeness and social identity. Rather, his chronicling of the popular performer’s protean facial expressions betrays his interest in her ability to morphologically transform into the characters populating her songs. Lautrec’s renderings of Guilbert also benefit from the tutelage he received from artist René Princeteau as a child. Indeed, Lautrec was taught by a man who, as a deaf sign-language practitioner, was particularly alert to facial expressivity in ways I propose to appreciate as “deaf gain.” Coined in 2014, the phrase aims to “counter the frame of hearing loss” and instead highlight the “unique, cognitive, creative, and cultural gains manifested through deaf ways of being in the world.”1

The narrow vertical format of this preparatory study centers Guilbert in the bottom register. Her body, molded in a sleeveless, structured, formfitting green dress, leans forward toward the viewer’s right. Her proper right arm extends into the composition’s upper register, its legibility challenged by its overlap with a meandering vertical line suggesting the stage curtain or perhaps a stage flat. While he uses repetitive lines to search and explore corporeal and sartorial outlines, the artist confidently applies restrained economical but evocative marks to shape the figure’s facial features. Fiercely angled eyebrows almost meet high on the forehead in a half circle, underneath which slanted swaths of diluted black paint weigh her lids with eye shadow. Two more inked lines mark her sharp cheekbone and the bottom of her nose, almost parallel to an elongated line of red pigment punctuated by two short peaks that form a thin mouth emphasized by carmine lipstick. Mounted on brown cardboard, Lautrec’s tracing paper allows the pure white pigment to register as judiciously placed highlights, denoting the complex lighting scheme of the cabaret space.

Throughout his career, Lautrec intermittently obsessed over one character or another. Yvette Guilbert became a favorite, and by 1894 he had devoted more sketches and lithographs to her than any other model.2 In fact, that year, with his friend Gustave Geffroy, he designed an entire lithographic album centered on the songstress. As Peter Wick writes in his introduction to the 1968 facsimile of the album: “Soon Lautrec’s interest in Yvette as a model was aroused to a fever pitch, un coup de foudre. He had tracked her down doggedly from song to song, from show to show.”3

What attracted Lautrec was the complexity of Guilbert’s performance. His fervor began with a diminutive depiction of her as a background element in a poster advertisement for the Divan Japonais cabaret [Fig. 2].

FIG. 2

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

French, 1864-1901

Edward Ancourt & Cie, printer

French

Divan Japonais, 1892-1893

Color lithograph

Plate/sheet: 78.4 × 59.7 cm. (30 7/8 × 23 1/2 in.)

Museum Appropriation Fund 40.016

The composition prominently features Jane Avril, a celebrity in her own right, shown here as a seated patron watching Guilbert onstage. The Divan Japonais was the site of Guilbert’s first professional success, yet in contrast to the monumentality of Avril’s solidly inked profile body, Guilbert is relegated to the upper left corner.4 Strikingly, Lautrec decapitates her. Her identity, however, remains unmistakable, denoted by her trademark gloves. Indeed, Lautrec, whose pictorial strategy for posters was to reduce performers to flat areas of color and key features or accessories, also drew on the silhouette Guilbert had designed for her stage persona.5

Although Lautrec excised Guilbert’s head in this first poster, he soon found her face a locus of physiognomic challenge and experimentation. As suggested by a letter dated July 1894, shortly after their first meeting, Lautrec offered to show Guilbert samples of his work in the hopes of creating an advertisement for her upcoming season.6 He set to work and produced a large-scale study now on display at the Musée Toulouse-Lautrec in Albi, France. This life-size sketch disappointed the singer, as revealed by a second letter:

Cher Monsieur,

I told you that my poster for this winter had been ordered already and is almost finished! Therefore, yours will have to be postponed. But for the love of Heaven don’t make me so atrociously ugly! Just a little less! A great many people who have been here screamed at the sight of the colored sketch.

Not everybody will look at it from an artistic point of view—and there you are!!

A thousand thanks from your grateful

Yvette.7

Following her entourage’s advice, Guilbert had instead selected Alexandre Steinlen to conceive her advertisement. The resulting poster shows an unrecognizable and sturdy Yvette on stage, looking out at the audience. Steinlen’s design does not imply motion or singing. Although he codifies his representation with Guilbert’s trademark red hair, V-cut dress, and black gloves, his portrayal of the performer aligns itself within the numerous arguably flattering yet ultimately nondescript representations of the performer.

3

FIG. 3

Louis Bernard-Saraz

“C'était bon (It Was Good),”

song / lyrics by Charles Delacour

music by Ludovic Ratz

created by Mademoiselle Yvette Guilbert

at the Concert Parisien, 1891

Bibliothèque nationale de France,

département Musique, VM28-3947

Is Lautrec’s attempt any more successful at reliably conveying Guilbert’s features? No. Her publicity photographs [Fig. 3] show her as fuller-faced and younger than Lautrec’s depiction, which has since been categorized as a caricature. Indeed, if we consider caricature to be the exaggeration of certain physiognomic attributes, the large sketch undeniably contains elements of the comic genre. And that, undoubtedly, was the contentious point of Lautrec’s submission for an advertising poster. Yet, retrospectively, Claude Roger-Marx argued for Lautrec’s and Guilbert’s suitability as artist and muse:

Between [Lautrec’s] style and Yvette’s there is a constant parallel. Sweetness and ferocity, triviality and refinement, phlegm and outrance, share an equal part in their designs, for Yvette “draws” herself each night, [. . .] the bursts of humor modeling a face whose proportions change every instant, which incite this other mime—the painter—to suggest and fix this mobility and this dynamism.8

Roger-Marx highlights Guilbert’s facial and corporeal transfiguration abilities and the duality of the personae she generated. The numerous posters advertising her act demonstrate that Guilbert, or the venues hosting her, long resisted a marketing strategy that promoted her homely appearance and ability to vacillate into caricature.

A shift occurred when she agreed to the album project pitched to her by Gustave Geffroy, who composed the text presented with Lautrec’s illustrations. This project consumed Lautrec from April of 1894 onward, and the luxurious original edition of one hundred (edited by L’Estampe Originale and published by André Marty) was made available for fifty francs on August 15 of that year.9 Critiques ranged from fervently positive to scathing, which made the album a succés de scandale. The most virulent voice belonged to Jean Lorain, who despised Lautrec. He spewed his venom in the Echo de Paris on October 15. He was present when Edmond de Goncourt received the album on September 2, delivered personally by Geffroy. Lorrain recalled Goncourt’s “startled air,” and declared:

No one had the right to push the cult of ugliness so far. I am well aware that Mlle Guilbert is not a pretty woman, but to have agreed to the publication of these portraits is . . . infamous. Mlle Guilbert has been blinded by her love of publicity; where was her feminine modesty and self-respect? . . . [Y]ou, Yvette, accepted these drawings [. . .] with their murky greens and those shadows that smear your nose and chin with caca d’oie. I come away deeply grieved, a trifle nauseated; I felt the vague and uneasy indignation that one feels at meeting a very pretty woman on the arm of a hideous lover.10

This last phrase, “a hideous lover,” reads as a barely concealed aspersion towards Lautrec. Gaston Davenay articulated more positive sentiments in his Figaro review on August 16:

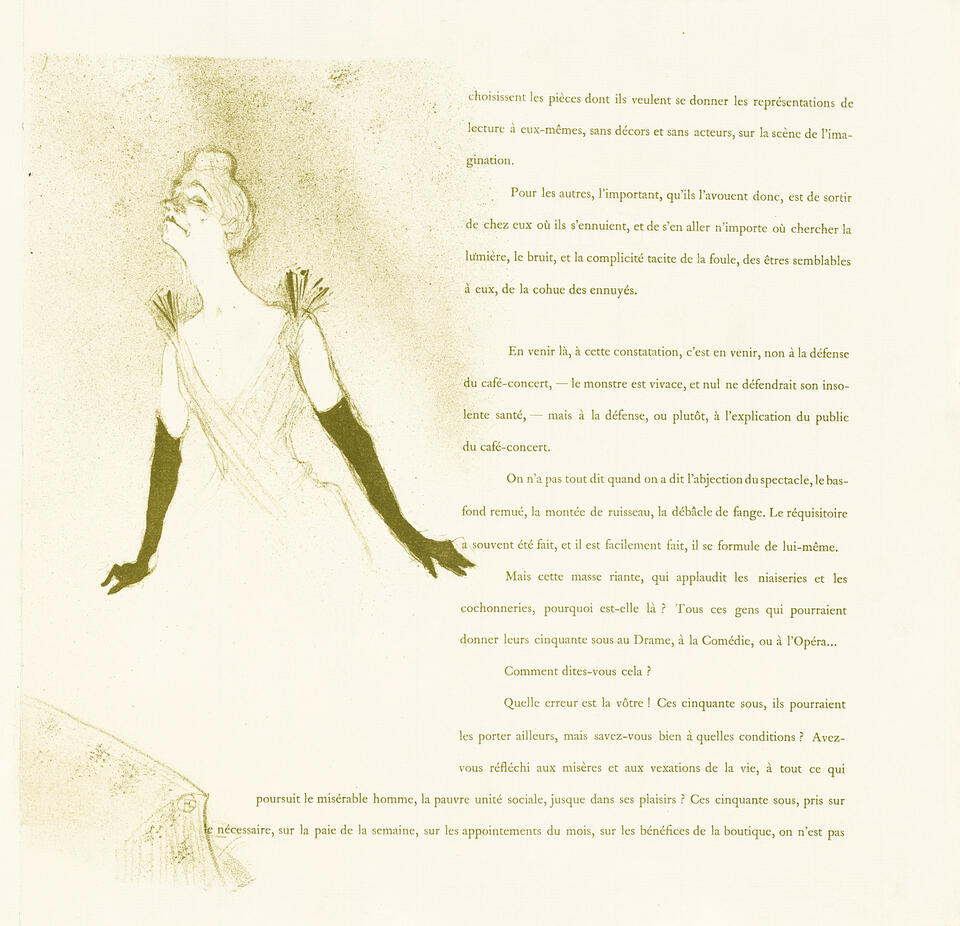

In these sixteen silhouettes of Yvette Guilbert, Toulouse-Lautrec is shown [. . .] a cunning observer in fixing the mimicry and the grimaces of the stage. We know the gift of transformation that is Yvette Guilbert’s. [. . .] Furthermore, along with the astonishing changing masks, Lautrec has drawn the delicious silhouettes with lightness and perfect grace. On each page one sees the divette undulate: the figure curves, the neck lengthens, the supple arms and slender hands rise, fall and trace their arabesques. All with delicate pencil, an art both robust and subtle.11

Despite her initial reservations, Guilbert’s wrote her satisfaction directly to the artist. She was delighted, and she understood that Lautrec’s seemingly acerbic hand served her brand of spectacle more efficiently than the rather bland representations by other artists plastered on the walls of Paris.12

For Lautrec did not “deform” Guilbert’s traits for deformation’s sake. His work demonstrates an attentive exploration of her vocation as a diseuse.13 Indeed, Guilbert did not just sing. She told stories. And she marshaled more than her voice to do so. The muscles in her face contorted to accommodate the dynamic modulations produced by her vocal cords, enhancing their effect. Dynamically, restraint succeeded accentuation and “in the tilt of an eyebrow, the movement of her lips, the expression of her eyes, she achieved a powerful degree of meaning and emotion.”14 Flattering the performer, or even faithfully recording her likeness, was of no interest to Lautrec. Rather, he aimed to convey her facial malleability and thus the experience of watching her as well as listening to her.

Contortion in the service of expression in fact resonated with Lautrec’s early absorption of pictorial representation, which had been (unconsciously) informed by exposure to a form of impairment other than his own.15 Although drawing was a common pastime among the members of the Lautrec family, around age seven young Henri received guidance from a friend of his father’s. Indeed, René Princeteau (1843–1914), a salon painter specializing in scenes of hunts on horseback, initially gave him sporadic advice while on holiday in the south of France. He soon tutored Lautrec more formally [Fig. 4] when the boy and his mother relocated to Paris in the mid-late 1870s, and most mornings the young student visited Princeteau’s studio and copied his sketches. Princeteau grew up deaf in an affluent family, with a devoted mother who taught him to read and write French. He attended a boarding school which insisted on oralism, the vocalization of language, but his preferred mode of communication was sign language.16 Facial expressions and body language function as significant communication elements in sign language.17 As authors Bellugi, Reilly, and McIntire (respectively professors of psychology and neuroscience at San Diego State University and director of the Northeastern University ASL Program) state in From Gesture to Language in Hearing and Deaf Children, “[F]or first time observers, signers’ faces appear to pass through a rapid series of grimaces and contortions.”18 The reason, they continue, is that in sign language, “facial behaviors function in two distinct ways: to convey emotion (as with spoken languages) and to mark certain specific grammatical structures.”19 Additionally, Gallaudet University deaf-studies scholars Bauman and Murray write:

Eye-tracking studies have found that fluent signers focus on the face when engaged in a conversation or perceiving signed language instead of following the hands. A number of studies since the 1980s have determined that signers have some superior face-processing skills because of their frequent attention to and processing of facial features and overall attend to facial detail better than nonsigners.20

Owing to the nature of his primary language, Princeteau was thus particularly alert to bodily and facial animation, a vigilance which greatly enlivened his graphic practice.21

4

FIG. 4

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Princeteau and Lautrec

(handwritten letter to the artist’s uncle), 1881

Pen and ink on paper

15.4 × 20.2 cm. (6 1/16 × 8 15/16 in.)

Photo © Christie’s Images / Bridgeman Images

By closely copying Princeteau’s sketchbooks as a boy, Lautrec was made alert to expressive physiognomies; he assimilated a mode of vision unlike that of the population at large. I do not propose that Lautrec saw like Princeteau, but that he absorbed representational strategies that took seriously motion and gesture (both facial and corporeal), the perception of which was mediated through “deaf vision” and early sign-language acquisition.

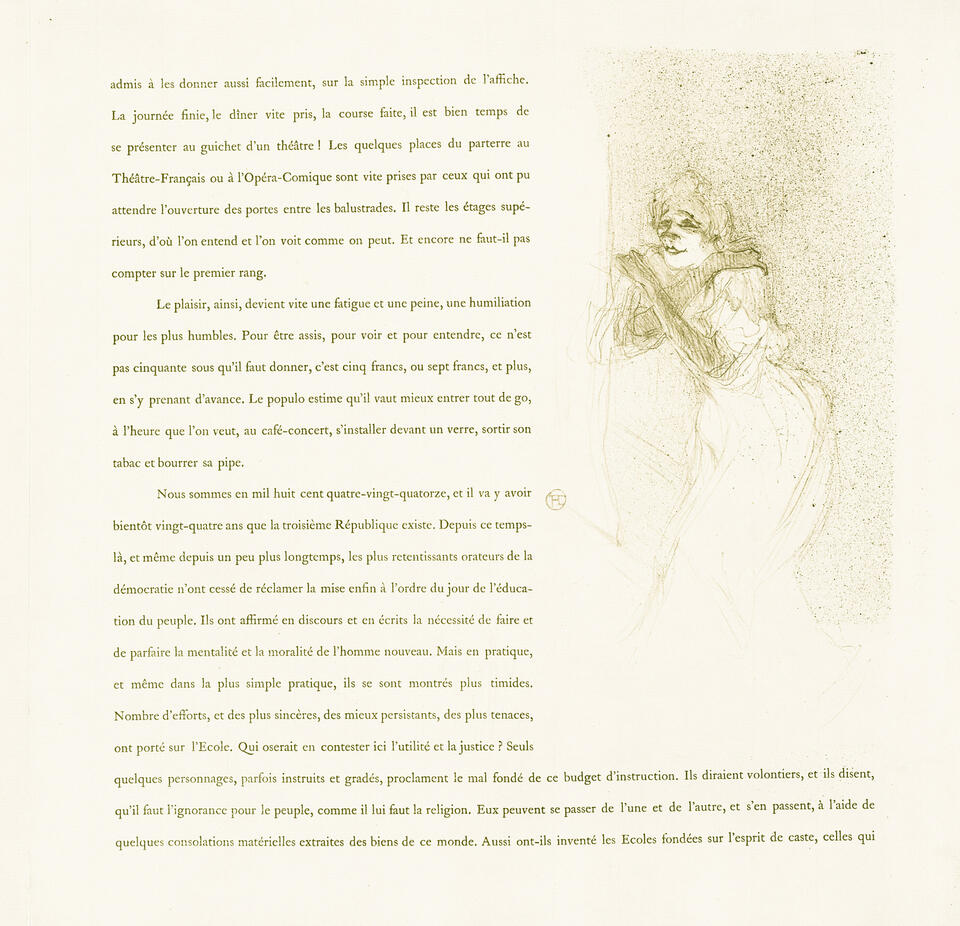

Although wholly able to do so, Lautrec never recorded Guilbert’s likeness. Additionally, achieving resemblance requires prolonged observation and therefore stasis on the sitter’s part, a state incompatible with Guilbert’s performance and the pathos of her act. Lautrec’s cursory line work speaks to his style, but also conveys the urgency of registration precipitated by Guilbert’s tremendous mobility. He insisted on catching her masks, a term chosen by Gaston Davenay in his Figaro review, privileging the fleeting over the constant, the pathognomonic extremes over the physiognomic baseline.22 His capture of fleeting elongation or contraction, pouting or grinning came at the cost of recognition. But Lautrec’s “sitter” was not Guilbert: it was her cast of characters. Key to this challenge was Lautrec’s seriality. No single image could adequately embody Guibert, since on stage “she” really was “them.”

5

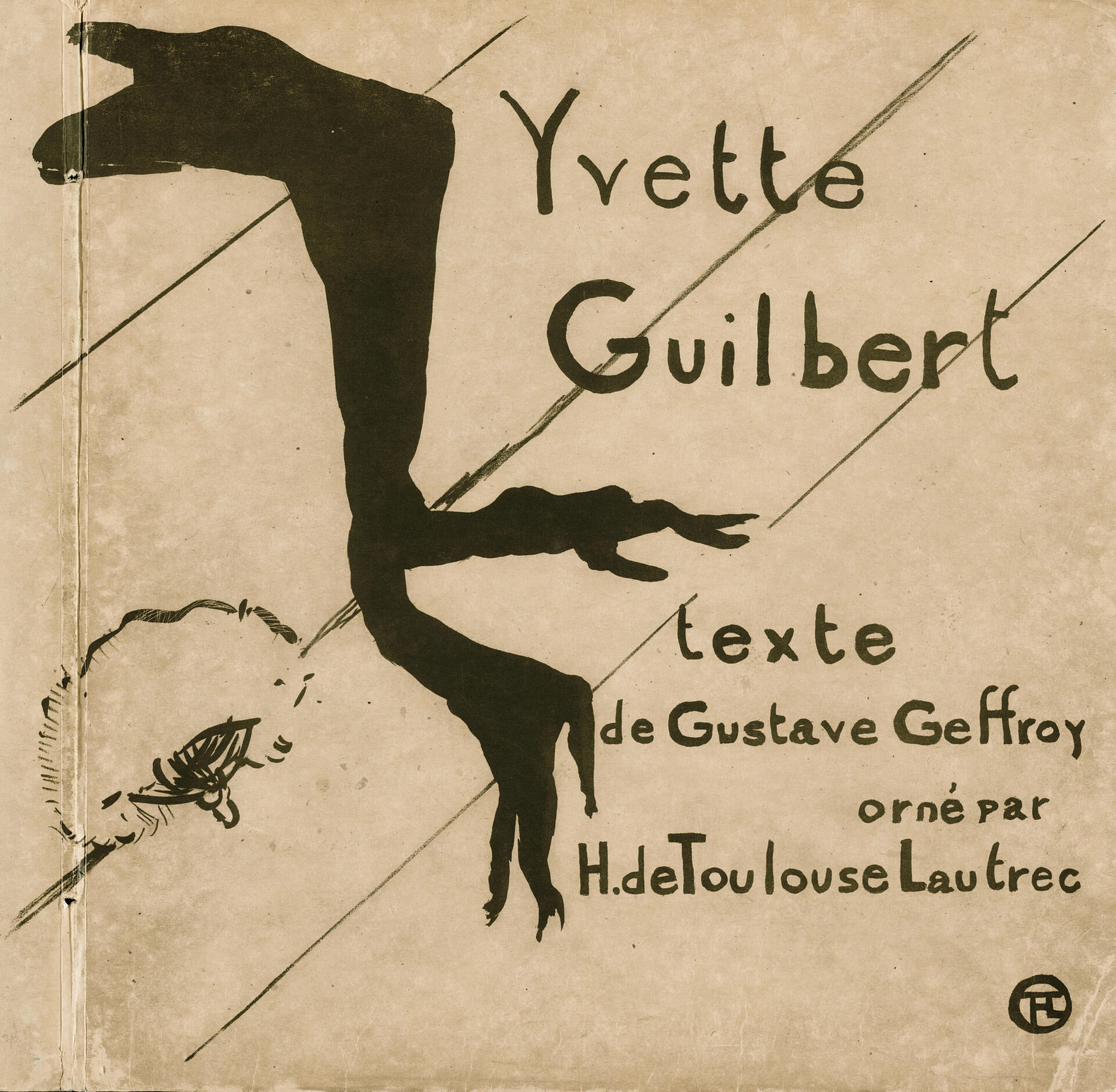

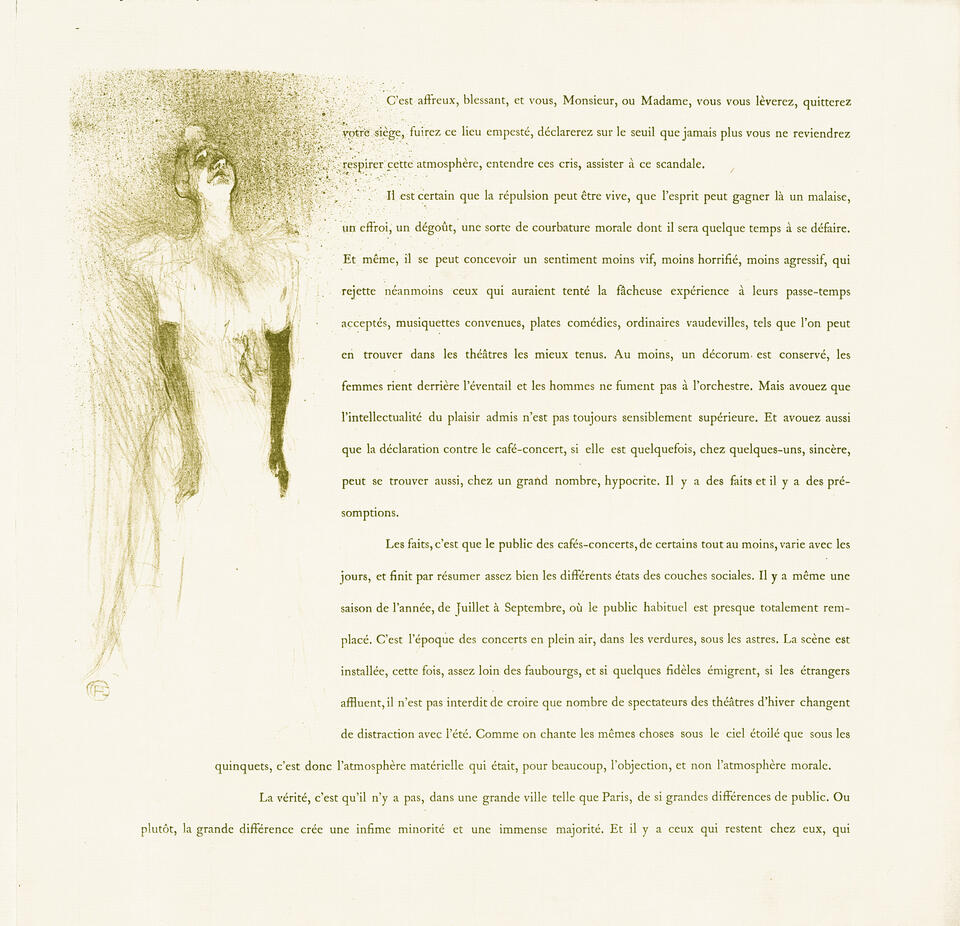

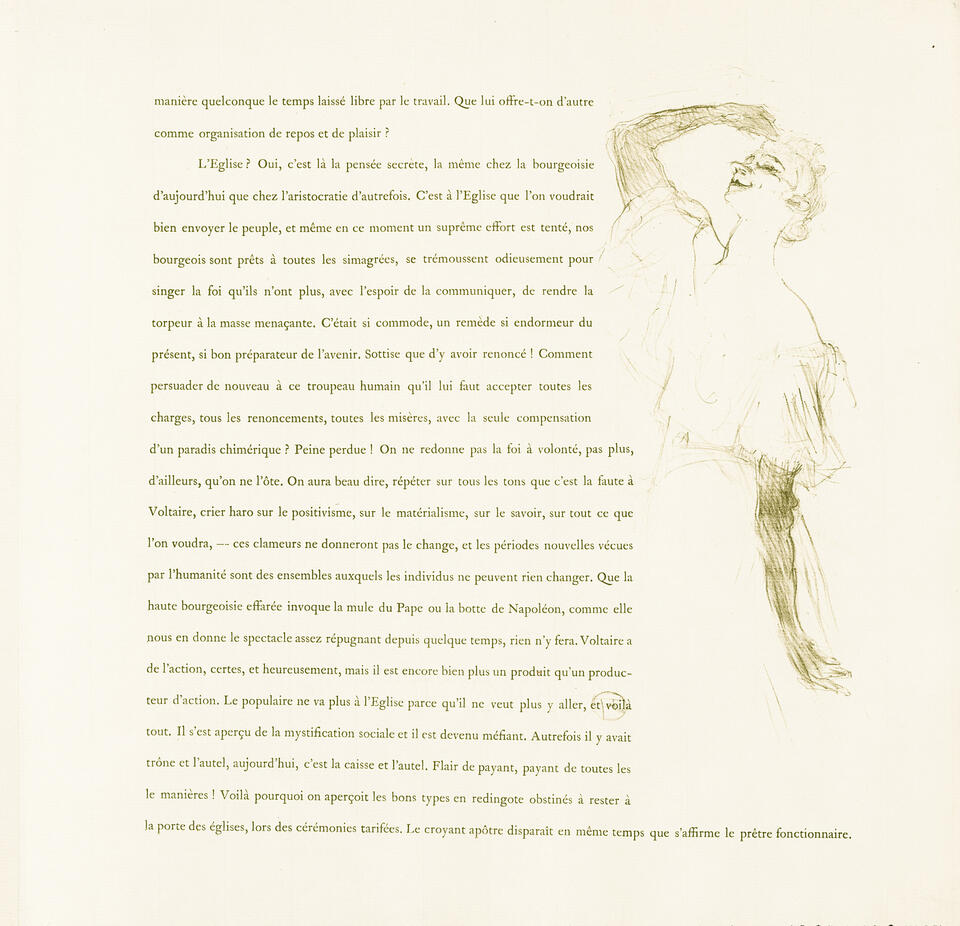

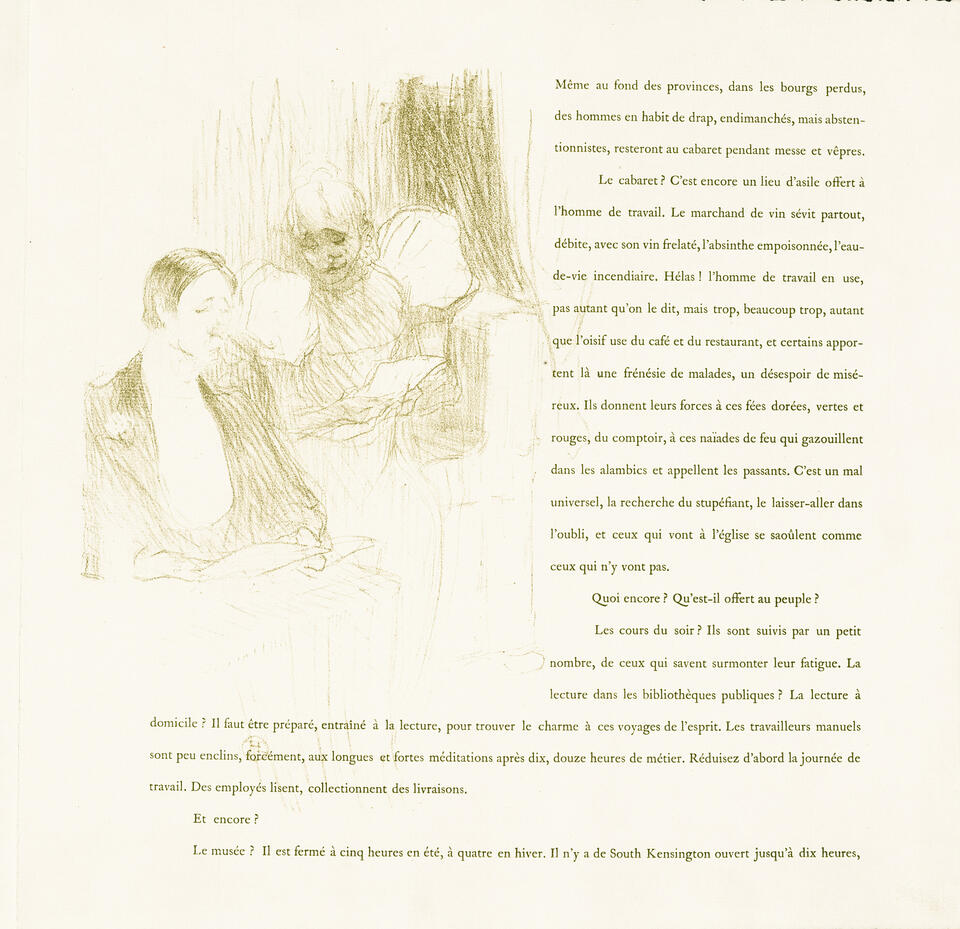

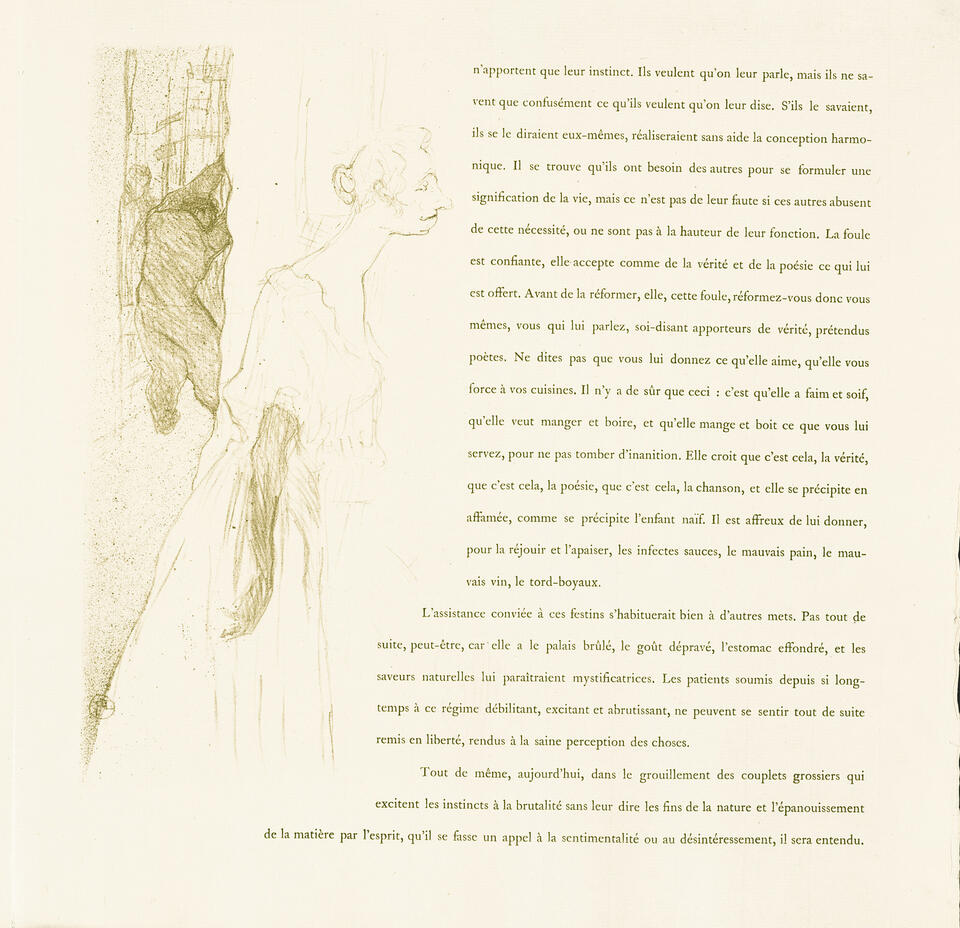

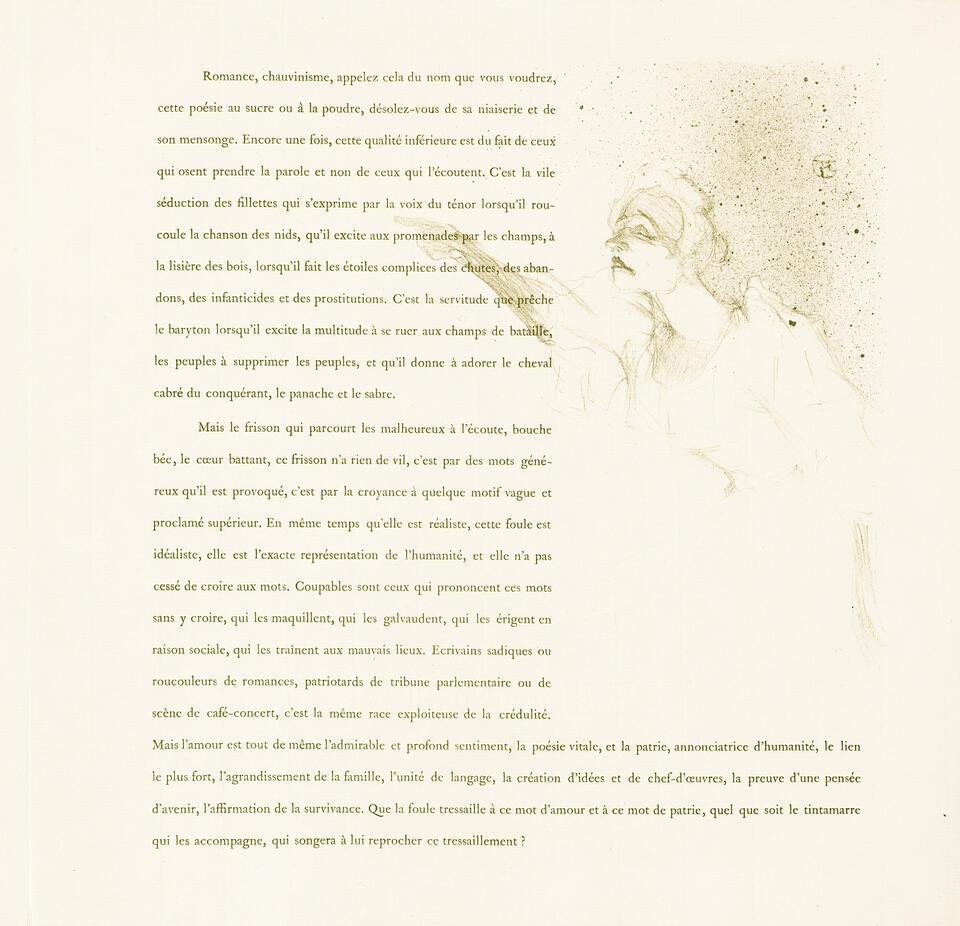

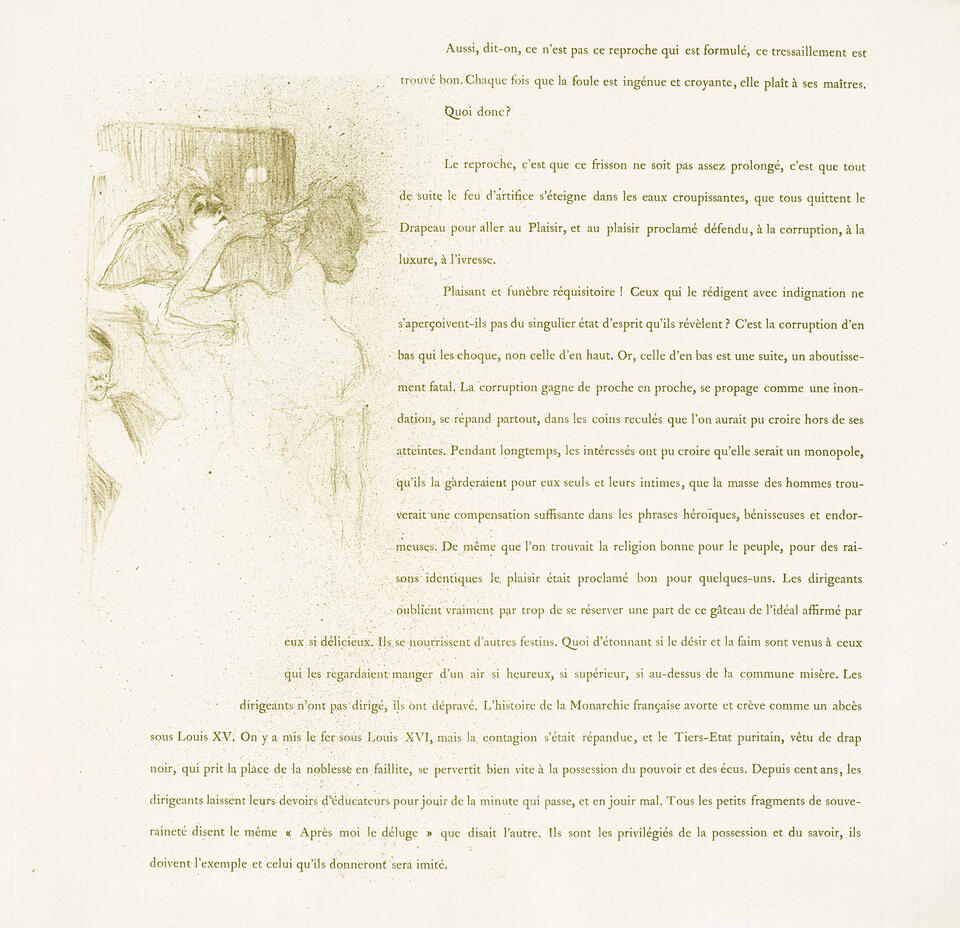

FIG. 5

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Cover and selected pages from Yvette Guilbert, 1894

Color lithograph, with letterpress, on ivory laid paper

Each approx. 40.8 x 39.4 cm. (16 x 15 1/2 in.)

Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection,

1931.49, 1931.52–.57, 1931.60–.62, and 1931.65

The Art Institute of Chicago

Images

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Page from Yvette Guilbert, 1894

Color lithograph, with letterpress, on ivory laid paper

Approx. 40.8 x 39.4 cm. (16 x 15 1/2 in.)

Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection,

The Art Institute of Chicago

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Page from Yvette Guilbert, 1894

Color lithograph, with letterpress, on ivory laid paper

Approx. 40.8 x 39.4 cm. (16 x 15 1/2 in.)

Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection,

The Art Institute of Chicago

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Page from Yvette Guilbert, 1894

Color lithograph, with letterpress, on ivory laid paper

Approx. 40.8 x 39.4 cm. (16 x 15 1/2 in.)

Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection,

The Art Institute of Chicago

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Page from Yvette Guilbert, 1894

Color lithograph, with letterpress, on ivory laid paper

Approx. 40.8 x 39.4 cm. (16 x 15 1/2 in.)

Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection,

The Art Institute of Chicago

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Page from Yvette Guilbert, 1894

Color lithograph, with letterpress, on ivory laid paper

Approx. 40.8 x 39.4 cm. (16 x 15 1/2 in.)

Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection,

The Art Institute of Chicago

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Page from Yvette Guilbert, 1894

Color lithograph, with letterpress, on ivory laid paper

Approx. 40.8 x 39.4 cm. (16 x 15 1/2 in.)

Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection,

The Art Institute of Chicago

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Page from Yvette Guilbert, 1894

Color lithograph, with letterpress, on ivory laid paper

Approx. 40.8 x 39.4 cm. (16 x 15 1/2 in.)

Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection,

The Art Institute of Chicago

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Page from Yvette Guilbert, 1894

Color lithograph, with letterpress, on ivory laid paper

Approx. 40.8 x 39.4 cm. (16 x 15 1/2 in.)

Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection,

The Art Institute of Chicago

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Page from Yvette Guilbert, 1894

Color lithograph, with letterpress, on ivory laid paper

Approx. 40.8 x 39.4 cm. (16 x 15 1/2 in.)

Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection,

The Art Institute of Chicago

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Page from Yvette Guilbert, 1894

Color lithograph, with letterpress, on ivory laid paper

Approx. 40.8 x 39.4 cm. (16 x 15 1/2 in.)

Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison Collection,

The Art Institute of Chicago

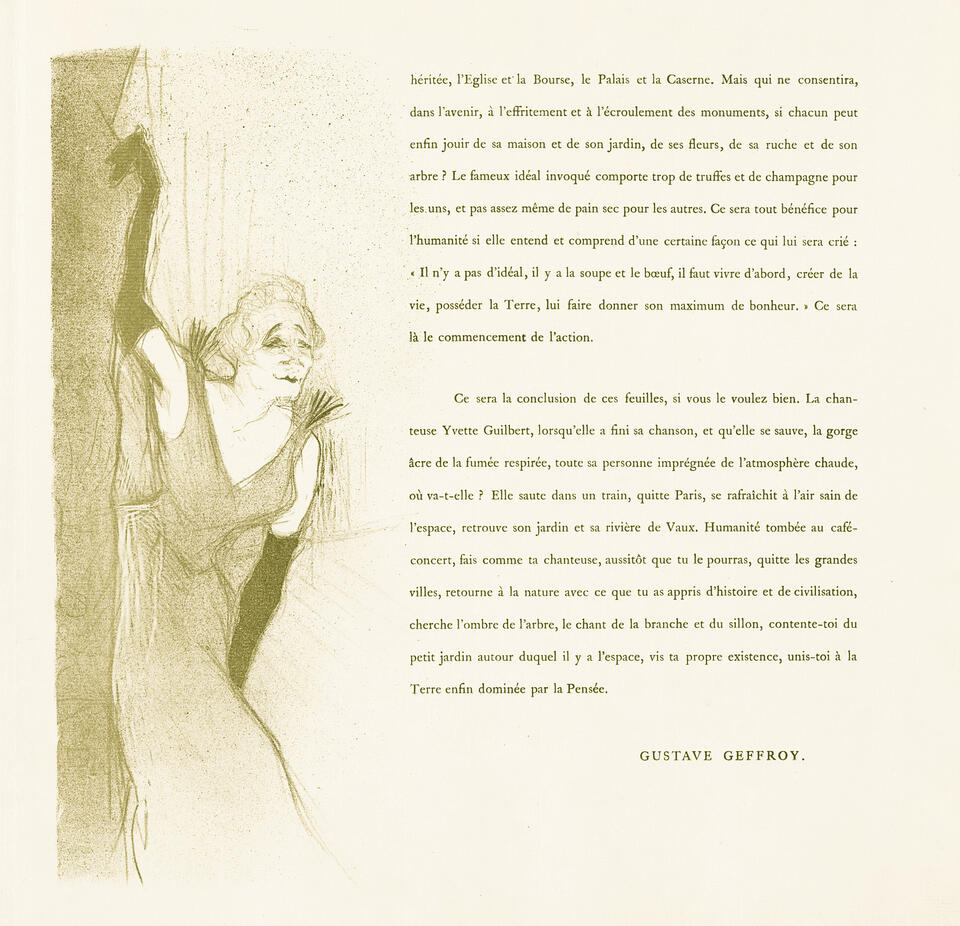

RISD’s multimedia preparatory study features as the album’s [Fig. 5] sixteenth lithographic illustration, now monochromatic but with few compositional alterations. Guilbert’s torso and face feel bit more upright, characterized by a starker distribution of highlight and shadow across the lower and upper part of the face, respectively. If we understand this last drawing as Guilbert’s curtain call, we may ask why Lautrec would still deploy a caricatural version of the performer when she is saluting her public, as herself. But again, and as Douglas Cooper writes, “[B]y this time, Yvette Guilbert had evolved a make-up and costume . . . to enhance her personality and distinctive features—a long neck, reddish hair, a comically up-tilted nose, and a broad, expressive mouth.”23 While onstage, she was still Guilbert the performer, not Yvette the private citizen. Consequently, Lautrec’s pictorial choices remain true to the experience of watching her act from beginning to end, and moreover produce a uniform graphic identity for the album as a whole.

From Lautrec, Guilbert eventually learned to sideline the vanity of youth and the requisites of advertising that favored sanitized and idealized representations. And Lautrec capitalized on Guilbert’s systematized silhouette to conjure pictorially the experience of both watching and listening to her sung stories. Furthermore, considering Lautrec’s oeuvre in terms of deaf gain, in light of his affiliation with Princeteau, contributes to conceptions of deafness that flip the narrative of loss: “Hearing loss comes to have a different meaning: the loss that hearing people experience by not being open to the benefits, contributions, and advances that arise through deaf ways of being.”24 Princeteau’s deaf gain enriched not only his own graphic work but, through his solicitous tutelage, also enhanced Lautrec’s artistic vision.

- H-Dirksen L. Bauman and Joseph J. Murray, Deaf Gain: Raising the Stakes for Human Diversity (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), xv. See also Alexandra Courtois de Viçose, “Deaf Gain: Toulouse-Lautrec’s Early Training with René Princeteau,” in Disability and Art History: From Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century, eds. Ann Millett-Gallant and Elizabeth Howie (New York: Routledge, 2021).

- Peter Wick, introduction to Yvette Guilbert, by Gustave Geffroy and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, trans. Barbara Sessions (New York: Walker, 1968; orig. Paris: L’Estampe Originale, 1894). Non-paginated.

- Wick, Yvette Guilbert, n.p.

- Wick, Yvette Guilbert, n.p.

- In Richard Thomson, Phillip Dennis Cate, and Mary Weaver Chapin, Toulouse-Lautrec and Montmartre: National Gallery of Art (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). See also Douglas Cooper, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (New York: H.N. Abrams, 1970), 114.

- Cited in Gerstle Mack, Toulouse-Lautrec (New York: Knopf, 1953), 195.

- Mack, Toulouse-Lautrec, 195.

- Claude Roger-Marx, introduction to Yvette Guilbert Vue par Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (Paris: Pont des Arts, 1950).

- Fifty francs represented a hefty sum in 1894 for this literary consumption of the café-concert, compared to the fifty sous (centimes) required to enter the physical cabaret. About this album, see also Jean Adhémar Toulouse-Lautrec: His Complete Lithographs and Drypoints (London: Thames and Hudson, 1970).

- Wick, Yvette Guilbert, n.p. Caca d’oie means “goose shit.”

- Quoted in full in Wick, Yvette Guilbert, n.p..

- Adhémar. Toulouse-Lautrec, xxxi-xxxii. See also Jean Bouret, Toulouse-Lautrec (Paris: Semogy, 1979), 146.

- Wick writes in Yvette Guilbert: “as to her style, she herself protested that she was neither a chanteuse (songstress) nor a divette (musical comedy actress), but a diseuse, a reciter of songs.”

- Wick, Yvette Guilbert, n.p.

- Lautrec experienced childhood leg fractures, stunted growth, chronic pain, and a permanent limp, likely resulting from a genetic disease—perhaps pycnodysostosis.

- Yvonne Pitrois, Silent Worker 26, no. 9 (June 1914): 166–67.

- Bauman and Murray, Deaf Gain, 134–35.

- J. S. Reilly, M. L. McIntire, and U. Bellugi, “Faces: The Relationship Between Language and Affect,” in From Gesture to Language in Hearing and Deaf Children, ed. Virginia Volterra and Carol Erting (Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press, 1994), 128.

- Facial expressions already were a component of French sign language when Princeteau was a practitioner, as expressed in Prosper Ménière’s De la Guérison de la Surdi-mutité. De l’Instruction des Sourds-muets (Paris: Germer Baillière, 1853), 236: “I don’t believe we have ever seen true deafs, complete deaf-mutes, converse by mouth when they could do so by way of fingers, or facial expression/sign language. When they meet, on the contrary, their hands, their arms, their bodies, their whole faces instantly and instinctively activate” (my translation). For more recent scholarship, see Hugo Mercier and Patrice Dalle, “Analyse d’expressions faciales en langue des signes,” Colloque des doctorants de l’EDIT (Toulouse, May 22–23, 2006).

- Bauman and Murray, Deaf Gain, 134.

- In contrast to his official Salon submissions. See Courtois de Viçose, “Deaf Gain: Toulouse-Lautrec’s early Training with René Princeteau.”

- Quoted in full in Wick, Yvette Guilbert, n.p. Pathognomy, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, is the knowledge or study of the passions or emotions, especially their resultant facial expression. The earliest use of the term is found in the writings of Thomas Holcroft (1745–1809). See also Alexandra Courtois de Viçose, “The Monstrous Gnome; Confronting Physical Difference in the Art of Toulouse-Lautrec,” PhD diss., (University of California Berkeley, 2018), https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/monstrous-gnome-confronti….

- Cooper, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 114.

- Bauman and Murray, Deaf Gain, xxxviii.

Cite this article as

Chicago Style

MLA Style

Shareable Link

Copy this page's URL to your clipboard.