What are the essential questions museums need to ask themselves to understand the future of art? On the occasion of the symposium To Search: Investigations of the Virtual and Material Lives of Objects, RISD Museum senior graphic designer Derek Schusterbauer interviews renowned graphic designer Rob Giampietro of Google Design NY “to search” for answers and get the perspective of someone designing emergent network systems and the structures of knowledge they create.

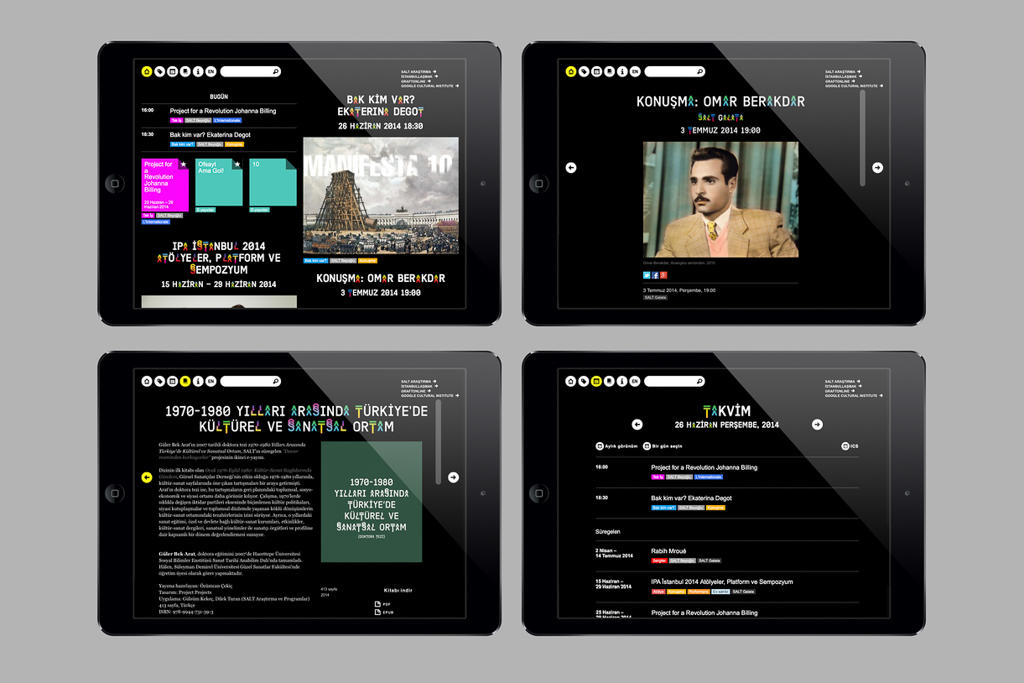

Derek Schusterbauer: In your time as principal at Project Projects, you did a lot of design work for art museums. What kind of digital presence were museums giving their objects while you were there, and in what ways were you suggesting they use interactive technology to give objects a life online?

Rob Giampietro: Maybe it’s best to respond to your question with the sort of questions I was hearing at the time. There were questions about how to represent objects in collections digitally. Some questions were technical: What’s the most future-proof format for documenting artwork?Some were legal: Does a museum own an object and its image? Should publicly funded museums release their images to the commons? Some were curatorial: Should the object be shown in various states of restoration? Should it be shown in isolation, in its frame, or in various exhibitions? Should it be documented at resolutions beyond what the human eye can see?

There were also questions about the interoperability of museum data. Should museums agree to standardized systems of cataloguing? How about art historical classification schemes or artist biographies? Should museums cooperate and share common technological platforms? Should these platforms be commercial or open source? Is the public allowed access to the data? What degree of access? How about other stakeholders, like third parties loaning objects to museums? Should they have the ability to communicate and track the distributed impact of their collections?

And there were questions about the character of the museum’s digital presence itself. What did it mean to go to a museum’s website? Were you visiting the museum virtually or simply reading one of its publications? What frequency was appropriate? How does a website reinforce or undermine a physical visit? What is the role of technology in the gallery space itself? How participatory should a gallery become? Is participation didactic? Are selfies allowed?

I could go on, but I’ll stop there. It’s a fascinating subject—the digital is free and fleeting, while the analog objects of the museum are priceless and largely permanent, so it’s a conspicuous and endlessly generative collision of worlds. The answers to these questions felt essential for understanding the future of art.

DS: To contrast, you are now doing design work for the single most innovative tech company our world has known. From the outside we see Google’s great ambition to turn everything in our world into data. How does Google’s view of the material object differ from that of an art museum, and what kind of ideas do you try to bring to the work you are doing for them?

RG: I often find it useful to return to Google’s mission, “To organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” I’m not sure I’d say the aim is to “turn the world into data” as much as to organize the information that comes from the world. Some of that means unlocking information that we didn’t have access to before, like the solar potential of our rooftops or the inefficiencies of our highways—that’s a form of access to something that was inaccessible before. And that’s also the case with a lot of art objects. One website might list a painting’s date and the artist’s biographical information, another might list shows where that painting has appeared along with critical reviews, another might give information on that painting as part of a larger art movement in comparison with historical events, another website may list the painting’s media, and so on. Making this information more useful involves assembling and structuring it: relating one bit to another within a larger model, and perhaps even processing unstructured information using sensors and machine learning.

This methodology is scientific, evidence based, and universalizing. During my work with museums I heard more about interpretation, expression, and localization. What made this work of art unique? What made it belong in this museum’s collection, or in this particular place? How did owning it and displaying it speak to what the museum itself hoped to impart to its visitors? How did it speak to its artist’s own individuality and expression? And how did this specific object critique or inform the world that produced it? These are different but not necessarily opposed methods; if anything they’re complementary.

DS: To contrast, you are now doing design work for the single most innovative tech company our world has known. From the outside we see Google’s great ambition to turn everything in our world into data. How does Google’s view of the material object differ from that of an art museum, and what kind of ideas do you try to bring to the work you are doing for them?

RG: I often find it useful to return to Google’s mission, “To organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” I’m not sure I’d say the aim is to “turn the world into data” as much as to organize the information that comes from the world. Some of that means unlocking information that we didn’t have access to before, like the solar potential of our rooftops or the inefficiencies of our highways—that’s a form of access to something that was inaccessible before. And that’s also the case with a lot of art objects. One website might list a painting’s date and the artist’s biographical information, another might list shows where that painting has appeared along with critical reviews, another might give information on that painting as part of a larger art movement in comparison with historical events, another website may list the painting’s media, and so on. Making this information more useful involves assembling and structuring it: relating one bit to another within a larger model, and perhaps even processing unstructured information using sensors and machine learning.

This methodology is scientific, evidence based, and universalizing. During my work with museums I heard more about interpretation, expression, and localization. What made this work of art unique? What made it belong in this museum’s collection, or in this particular place? How did owning it and displaying it speak to what the museum itself hoped to impart to its visitors? How did it speak to its artist’s own individuality and expression? And how did this specific object critique or inform the world that produced it? These are different but not necessarily opposed methods; if anything they’re complementary.

DS: Somewhere in between these two extremes you were awarded the Katherine Edwards Gordon Rome Prize for Design 2014–15 and spent time at the American Academy in Rome. How did the more personal project you worked on there influence your ideas about material objects and their digital representations?

RG: In some ways my time in Rome helped to synthesize for me these two methodologies I’ve described, universalizing and localizing. For all its many small museums, churches, and foundations, Rome is almost its own generalized museum, a city-sized museum filled with objects that originated there, many objects that were taken there through various empire-building campaigns, and virtual representations of what once existed.

Much of my own walking and writing in Rome centered on these elements that highlight a connection between the city and its technologies of representation. At the Palazzo Valentini you can walk into a space layered with four major moments in Roman history, from an ancient bath complex to a fascist bunker, all of which is experienced using glass floors, animated renderings, and projected choreographed digital effects. Here the digital invokes the ancient. The Vatican Map Room, a hallway covered with floor-to-ceiling frescoes, was the immersive Google Maps of its day. Renaissance artists were constantly trying to innovate techniques that transformed one material into another—glass into light, stone into flesh—in a way that makes the digital/analog divide seem quaint. And Rome has been continuously inhabited for so long that technological innovations, along with the social questions that arise as a result of those innovations, basically come with the territory.

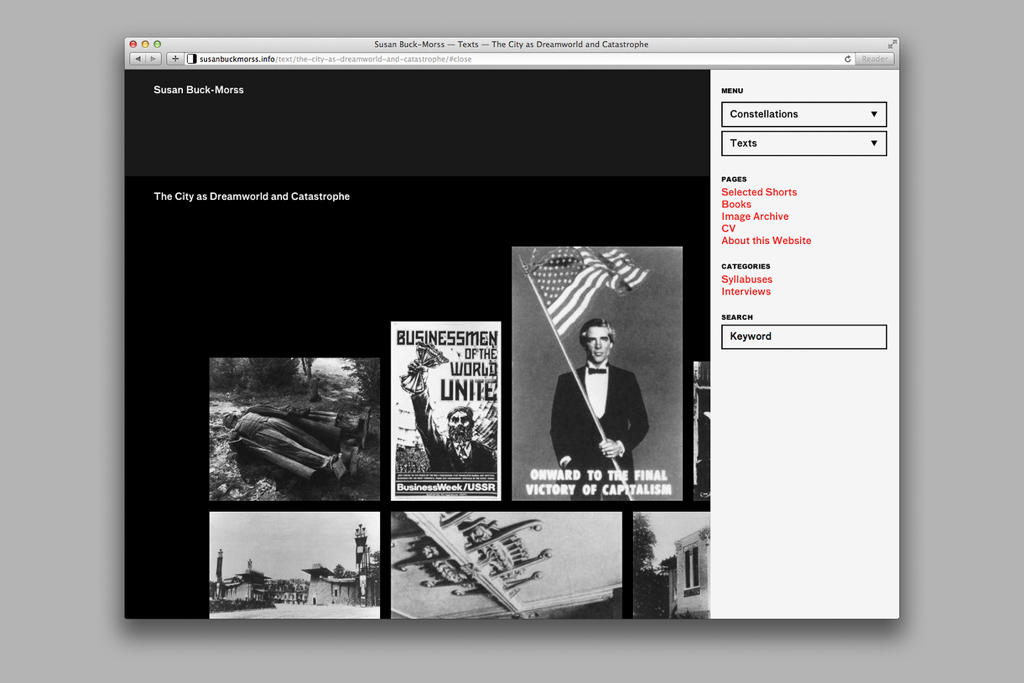

DS: As your graphic design work often results in websites and interactive pieces, it doesn’t result in a material object. Museums have recognized this, and have accessioned digital works from videos to typefaces and video games. What other digital works are they collecting or overlooking? How are they being represented in collections?

RG: Collecting is cohering, so to add digital works to existing analog collections is to look for ways the digital objects can extend and be coherent with what is already there. This is why videos, digital typefaces, and even video games are easier to incorporate. Videos are like films, digital typefaces are connected to typographic history spanning centuries. A lot of early digital arcade games came encased in forms that resembled pinball and other analog games.

As things grow larger, more integrated, and more systems-based, it becomes increasingly difficult to collect the “whole” thing, so you have to choose what part will represent the whole. You may have a film of a dance performance. A floorplan and checklist from an exhibition. A single sign from a larger campus wayfinding system. A fragment of architectural ornamentation from a skyscraper.

Your question was about what museums overlook in their collections. It’s tempting to see a collection as neutral, but of course it’s not. A collection is constantly reinforcing and modifying itself to better empower its host institution—which makes a collection sound a lot like a codebase, I suppose. Perhaps the web will collect itself!

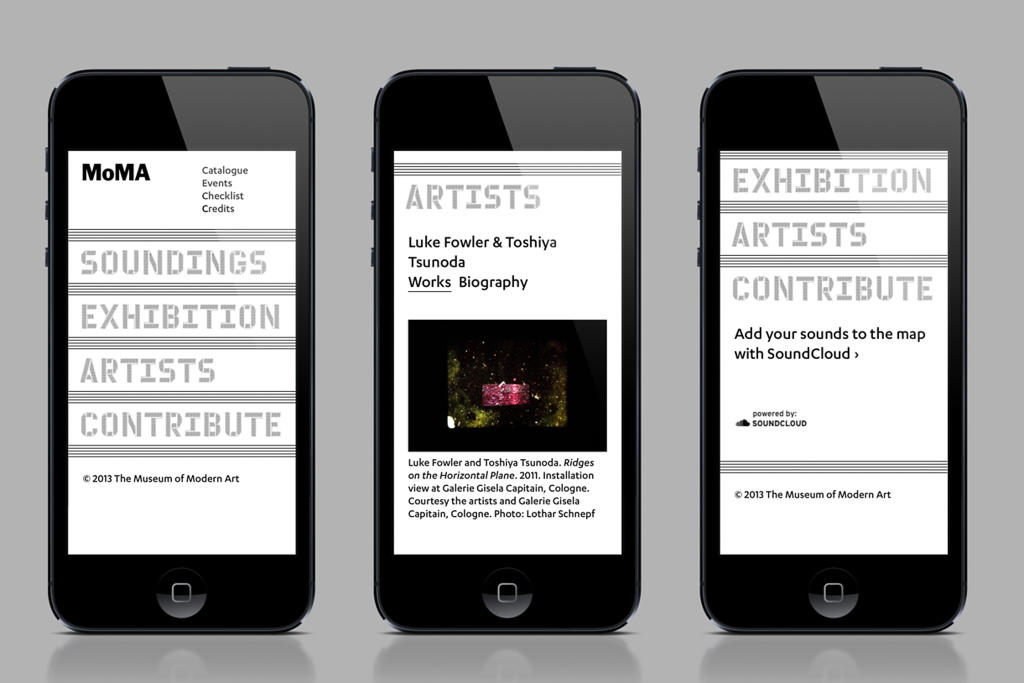

DS: In your article for Art in America, “The Museum Interface,” you assert that an important role of the art museum is to offer a true opportunity for cultural discourse, and that this is where interactive technology might best be utilized. That the digital representation of a work isn’t meant to replace an “encounter with the work [that] could be personal or transformative.” What would a successful digital program (interface) like this look like? Where does it lead to? Is it capable of also being a transformative encounter?

RG It’s important for people to see physical artworks up close in order to understand them in a deeper, more meaningful way, and I don’t think museums should worry about their webpages drawing visitors away from their galleries. That was the crux of my point. If anything—and I’ve written about this before in an essay called “Form-giving” that uses Lewis Hyde’s book The Gift as a framework—I think artworks are constantly revitalized by sharing and exhibiting them. So the web and other interactive media can certainly be part of a transformative experience too, but balance is required. It’s not good in a movie if the background music is louder than the essential dialogue. The same is true for interactive devices in the gallery. They shouldn’t interfere with your physical presence or others’ appreciation of an artwork up close. People often write as if it’s an either/or, but of course it’s a continuum.

My co-author of the Art in America piece, Sarah Hromack, and I spent a lot of time discussing Kara Walker’s Creative Time commission A Subtlety and its mediation through Instagram and other social channels, and here the continuum is evident: at first the network underscored the intensity of physically experiencing the work, but when it started to overshadow the actual work, people were right to question its benefit. Technology should be more aware of these very human considerations, but they should also be part of our own moral education as users.

DS: Is it a matter of addressing the viewing of artwork as an event rather than just something one looks at?

RG: I think there’s something inherently experiential about art, certainly. It can be very philosophical also. An event is over when it’s over, but art endures and changes, that’s one beautiful aspect of it. Maybe I’m backing into this metaphor, and like all metaphors it’s deficient in some aspects, but it’s tempting to see art as a kind of code—it’s created, it helps to power a larger system, it’s owned and then made public, maybe for a time it’s put aside or left out and then it takes on new meaning or use, so others build on it, respond to it, etc. I could be describing a GitHub repository.

DS: Can technology offer an idea about what one is not seeing, as much as what you are seeing, when viewing an image of a work of art? That a work of art is not an 800x600 pixel jpg but actually something else entirely? Can technology be or does it have any responsibility to be critical of itself?

RG: It can remind you that it’s not the real thing, sure. And that can be important. Hyde says the way you treat a thing can change its nature, and putting art online changes it. But it’s part of a trajectory, something Walter Benjamin described and that John Berger picked up on in Ways of Seeing—art that’s ubiquitous, reproduced, and in a different context than its source. At the same time, I’d bring in the great computer scientist Alan Kay, father of the GUI [graphical user interface], who said if you’re going to make a digital tool, make it meaningfully different from the original. Don’t make an eraser that leaves a mess all over your digital art board, make a magic eraser that erases effortlessly. And I think what he meant is that this new feature is the critique that’s built into the tool. Progress may be illusory, but it seems like a lot of technology is a kind of critique of the present. So yes, I think technology has a responsibility to be critical—I don’t think it can help it.

Rob Giampietro is a designer and writer. He is currently the creative lead for Google Design NY. He was a 2013 MacDowell Colony Fellow and the 2014–2015 Katherine Edwards Gordon Rome Prize Fellow at the American Academy in Rome. From 2010–2015 he was principal at Project Projects, where he led interactive and identity projects for clients in art, architecture, and the cultural sector. The studio’s work was recognized with the National Design Award in Communication Design in 2015. Rob runs the blog linedandunlined.com.