INTRODUCTION

Mokingpu

Susan Sekaquaptewa

Hopi

Basketry Plaque, late 1800s

Rabbitbrush, sumac, or willow with yucca,

kaolin, and pigment

Diam.: 45.1 cm. (17 ¾ in.)

Museum Works of Art Fund 44.582

My work as a grower and my perspective as a Hopi leads me to wonder and admire all that our precious Mother Earth gives us. As a lifelong student and with her as my classroom, I’m always learning the many different ways she brings nourishment and beauty to our bodies and souls.

The Hopi people are one of the earliest occupants of the high desert landscape of northern Arizona. We believe we were destined to call this place home, and we have lived here for many centuries. Despite a rainfall measurement of less than ten inches a year, we have learned to not only live but to thrive here. We see and value the abundance that this landscape offers. People who are not from this region often view our homeland as harsh, inhospitable, and wanting. I once hosted a couple visiting from France. As I was talking about the fields we planted and the beef cows we raised, they wondered, “What do the cows eat? We don’t see any grass.” Our landscape doesn’t appear to hold obvious value or useable assets.

Colors in my region don’t fight to be noticed. They simply complement each other, offering instead depth, layering, and texture. Similarly, my Hopi cultural lifeways mimic this cooperative approach, as we balance our lives here with responsibly using what the landscape offers us. We are stewards of this Earth first. Most everyone in our community learns what others call art. Our culture encourages weaving (both basketry and cloth), carving, pottery, and drawing, and we nurture and help teach one another. When you learn those forms, you begin to learn more about the world around you. Your eyes are opened wider.

If you really take the time to observe the northern Arizona landscape, you’ll notice various shades of greens and yellows. If you are lucky to be out during a particular time of the year or after life-giving rains, you’ll see lavender and pops of reds and yellows. You start by learning plant names. You then learn where they grow, if they are an annual or perennial. As you visit them every year, you will begin to note just how dependent they are on the summer rains or winter snows. Finally, you begin to know who they are and what they can offer you. You appreciate their beautiful range of browns, deep yellows, and sage greens, their undertones of browns and dark purples.

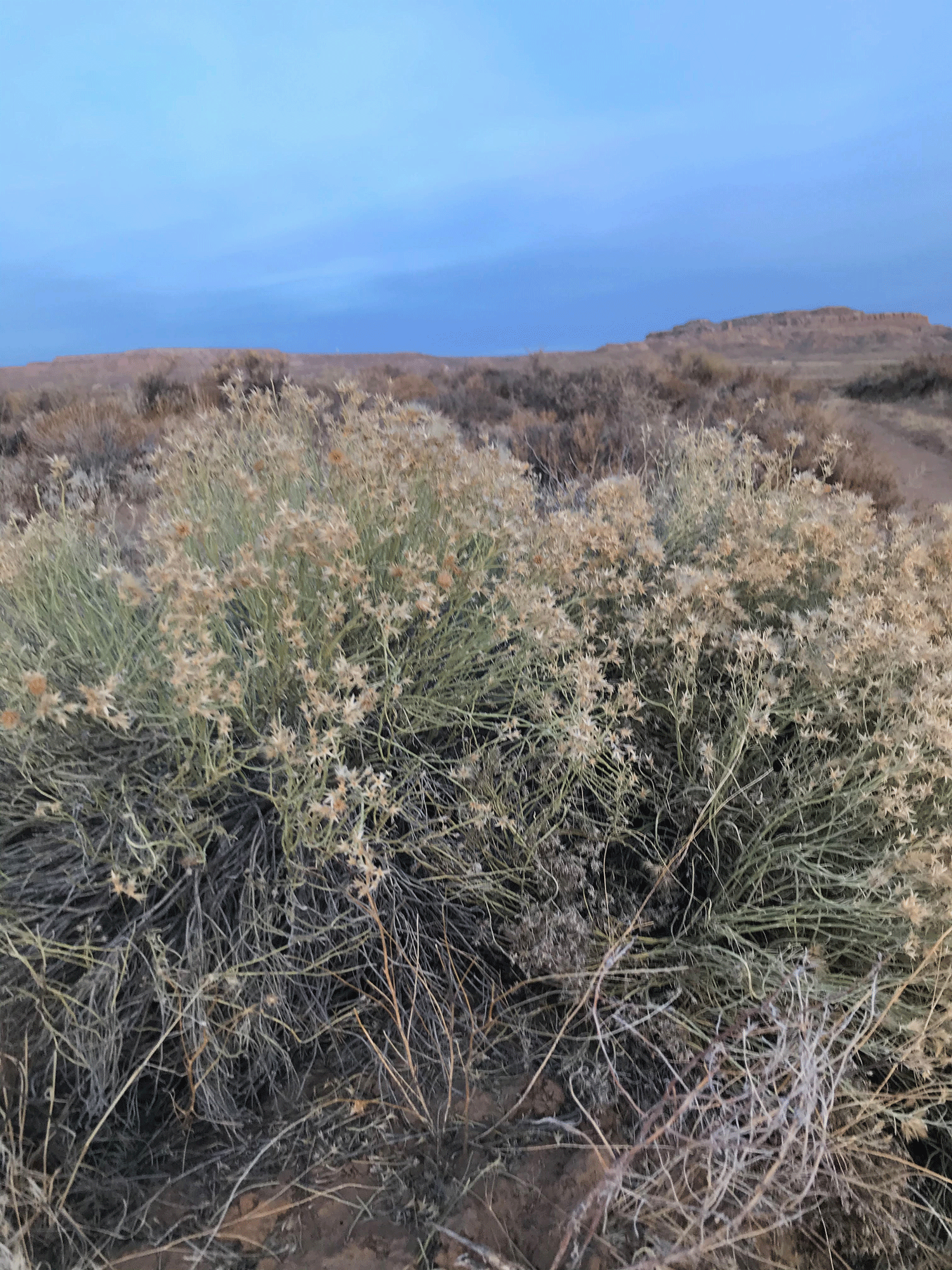

Sivaapi (Hopi for rabbitbrush, or Chrysothamnus) or maa’ovi (Hopi for snakeweed, or Gutierrezia sarothrae) are harvested and used to make color. When boiled down in water, they offer beautiful green, earthy hues. These are not bold greens. These plant hues mimic the broad strokes of the soft, opaque, warm colors found in our desert landscape. They can be used to dye yucca used to weave designs into our baskets or to paint wood carvings that represent earth spirits. They may be used to dye wool or cotton string to modestly decorate our woven traditional clothing.

The stems of the sivaapi plant are straight, slim, and strong. Harvested by women in the late summer, they are stripped of their light green sheathes and dried for weaving a particular type of basket. Sivaapi is also used to make a temporary brush for applying any kind of liquid. Their dense flower tops hold moisture well; they are cut to serve that purpose and discarded shortly thereafter.

Mooho (Hopi for narrowleaf yucca, or Yucca angustissima) is another wild plant that offers beautiful green to our landscape. Its mild color stands out against the warm brown sand that it grows in. Weavers learn to dry the harvested plant in a way that keeps its natural green color intact, so it can be used for decorative elements. They also learn to let the sun bleach out the color to white so it can be dyed using other wild plants.

Rubber rabbitbrush, or sivaapi, in the Hopi landscape. Photographs courtesy of Susan Sekaquaptewa

Like anything, you appreciate plants more when you develop a relationship with them. The relationship is reciprocal. We offer gratitude for what they give us, and we pray for the rains and the sun that nourish them. We think about them as the seasons change and pray that they will multiply and replenish as they should. New life is always shown to us through mokingpu, the color green—the light green stems of rabbitbrush, one of the few colors seen in the winter; the tender green shoots of new corn that emerge in the spring against the backdrop of the dry brown earth. Green offers hope. Green represents life.

Cite this article as

Chicago Style

MLA Style

Shareable Link

Copy this page's URL to your clipboard.