It began when RISD Museum curators Kate Irvin and Laurie Brewer said, “We want something different.” This was early 2012. Planning for Artist/Rebel/Dandy: Men of Fashion, the Museum’s major show for spring 2013, was well underway, with the photography for the accompanying book slated for summer of 2012.

RISD Museum object photography generally follows typical museum practice: a straightforward approach to framing and lighting with great concern for color fidelity. It’s a fairly neutral style that allows the object to come forward without obvious interpretation. With costume and dress objects, that usually means mannequins shot against a neutral seamless background. So I was quite intrigued when the curators suggested that this book go in a different direction.

Group of suits worn by Richard Merkin, Bertrand Surprenant, W. F. Whitehouse, Guy Hills, Patrick McDonald, Mark Pollack, and Charles Rosenberg.

Kate and Laurie showed me examples of what they hoped to do. They were especially interested in art images, such as the photographs ofMcDermott & McGough, Tanya Marcuse, and Rosamond Wolff Purcell. The book would almost exclusively feature works from the Museum’s own collection, and it was the curators’ desire to not use any mannequins, opting for tailors forms, racks, and other props instead. They clearly were less concerned with description in the photography and far more interested in evoking mood and atmosphere. I was excited, and began figuring out how we might accomplish this challenge.

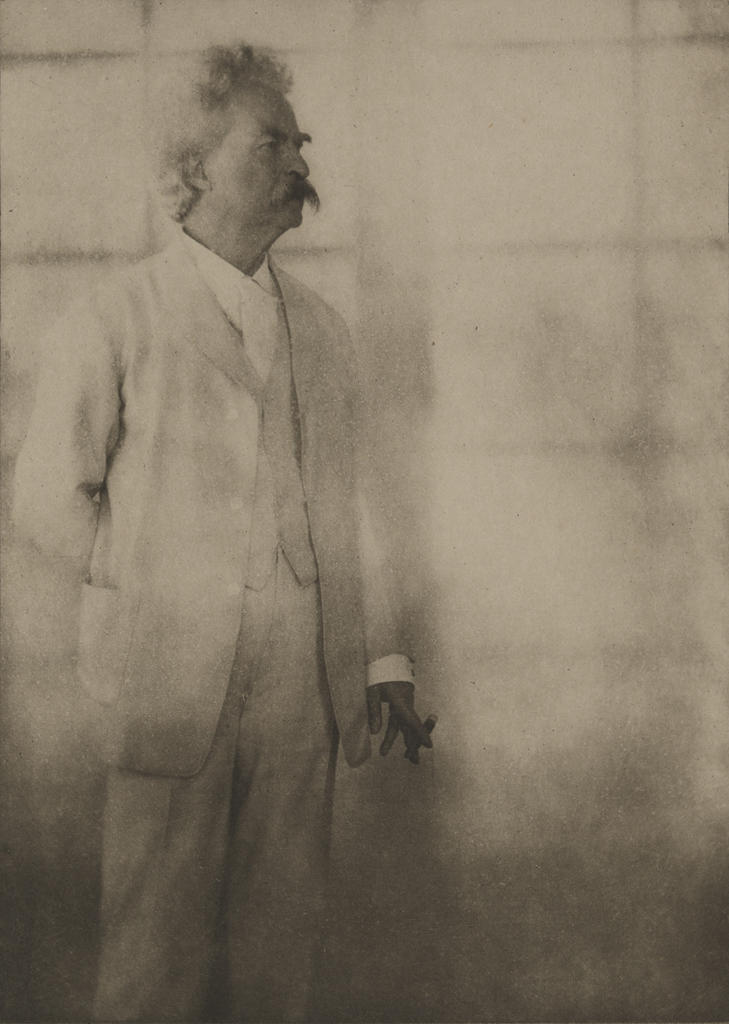

Alvin Langdon Coburn, Mark Twain, 1908, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. V. Duncan Johnson in memory of Julia Angier Ewing and Colby Mackinney Keeler 80.003

I started by assembling examples and inspiration images, using the curators’ group as a jumping-off point. I have a fine arts background and an interest in antique and soon-to-be antique processes, and I enjoyed indulging these interests. I was drawn to Photo-Secessionist work, especially that of Alvin Langdon Coburn. Coburn’s portrait of Mark Twain (in the Museum’s collection) provided inspiration on a number of levels. I also looked Richard Avedon and Irving Penn, and contemporary fashion photographers Patrick Demarchelier and Ellen von Unwerth. The work of Toshihiro “Tommy” Oshima, a photographer I found on Flickr a number of years ago, inspired me and served as guide throughout this project.

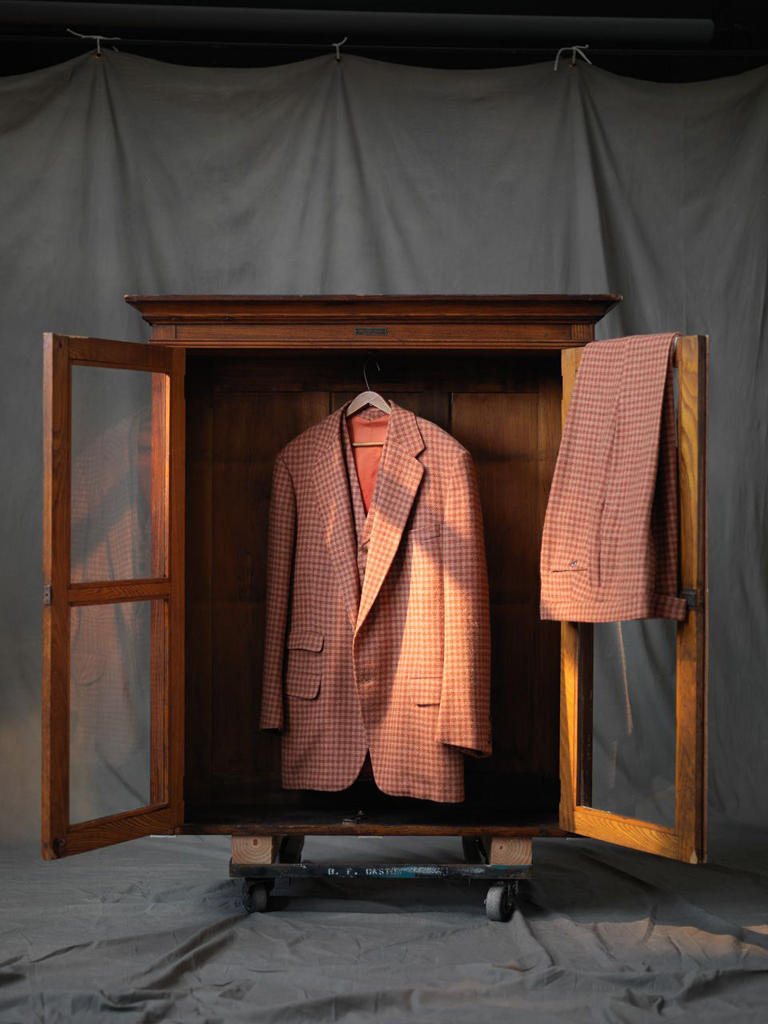

Suit worn by Richard Merkin, 1968. F. L. Dunne and Company, tailor, New York and Boston, est. ca. 1910. Wool twill weave. Gift of Richard Merkin 1999.65.2.

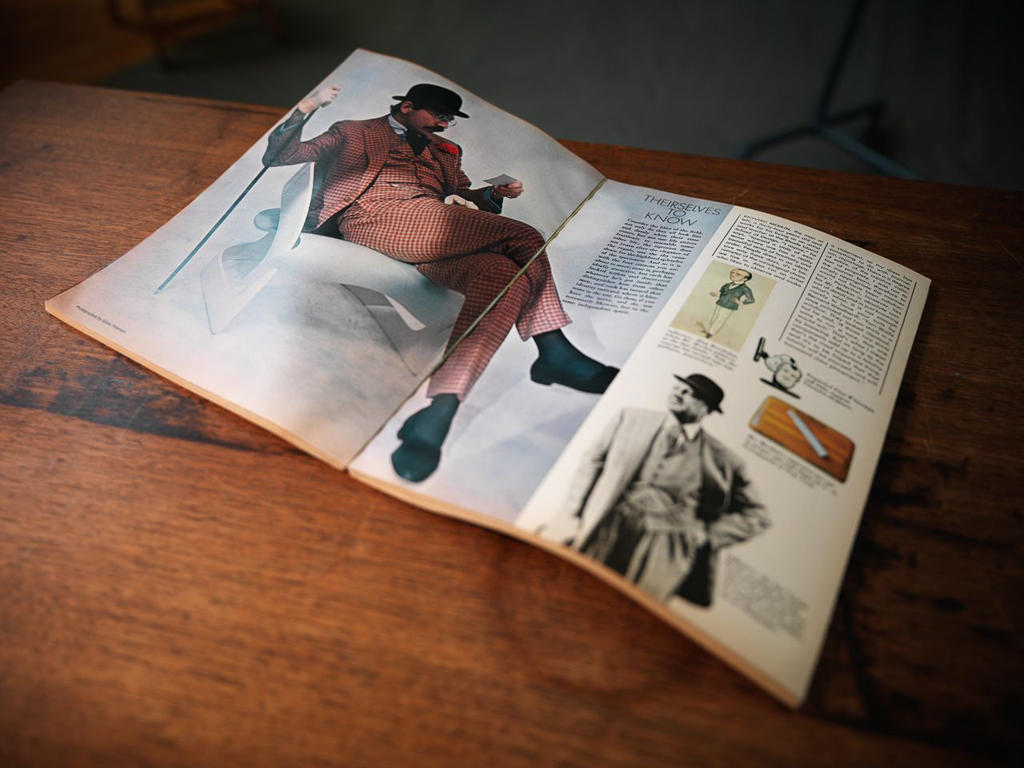

Richard Merkin wearing F.L. Dunne suit (now in the collection of the RISD Museum) and contemplating his own self-portrait, inEsquire, The Magazine for Men, December 1972. Gosta Peterson, photographer.

The next meeting with the curators explored possibilities. Wet plate collodion and printing cyanotypes on the roof were rejected as too impractical, but favorite ideas emerged. We talked about the role of photography and the photo shoot in fashion, and decided to pull back on the framing of shots, letting the studio and gear into the image. We loved the idea of using Polaroid, or in this case Fuji instant material, for its aesthetic qualities and as a nod to its place in the fashion shoot. We were also aided by the discovery of a detail related to one of the key objects and personalities of the exhibition: an orange suit owned by the late RISD professor and self-proclaimed dandy Richard Merkin. Esquire had photographed Merkin in this suit, lounging on a chair, looking at what seems to be a small piece of paper. We learned from photographer Gosta Peterson that he was looking at a Polaroid of himself.

Group of collars worn by Francis J. Carolan, ca. 1900. Starched plain weave cotton. Anonymous gift 82.053.8.

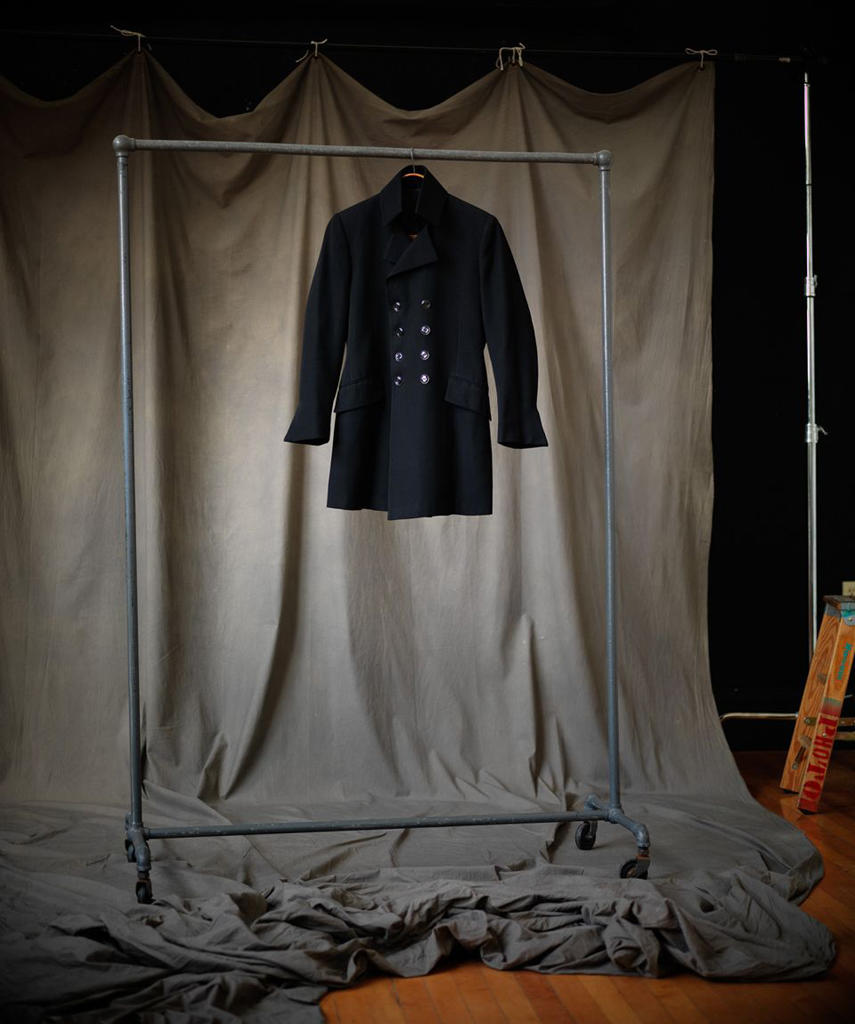

Given the range of dates for our 75 objects, one challenge was suggesting period without becoming too specific. We agreed that we were not creating tableaux but evoking a style—quoting and borrowing, just like the designers featured in the exhibition. Our photo shoot would mix eras and not be too literal about period. Kate Irvin sourced paneling and cabinetry from a defunct men’s shop in Providence and we employed a number of tables around the Museum; some were objects from the collection and others—our favorites— were utilitarian pieces used for various functions and events. As a base backdrop for many of the shots, we adopted a painted muslin drop, adding texture, softness, and a classic look.

Three-piece suit worn by Bertrand Surprenant, 1959. Kilgour, French and Stanbury, tailor, London, est. 1882. Wool basket weave (plain weave with paired warps and wefts). Gift of Bertrand Surprenant 80.253.1.

Lighting, of course, is all-important, and we very much admired studio natural-light portrait and fashion photography from the 19th and 20th centuries. Our studio has north-facing windows and skylights, although it had been many years since natural light had been used for photography there. I cranked up the black shades and used that northern light, supplementing its cool softness with tungsten light from Fresnels and tota-lights to add in harder accents and warmth. The hot lights were sometimes filtered for correction and sometimes not, depending on what seemed to work best within the shot. The day-lit studio was a joy to work in; it made everything look its best. It seemed that almost all we had to do was place an object on the set and stand back, but after a few “wows” early on, we realized even sunlight could be improved. I’d add in lights, use fill cards and mirrors, and sometimes use flags and other things to break up the light. The changeability was sometimes tricky and at least once I had a long thunderstorm delay, but it was great to appreciate the changing light throughout the day.

The approach evolved during the shoot. The primary shooting was done on digital. My main camera system is the Hasselblad H4-200 and Hasselblad lenses. Natural light gave me an opportunity to see how the lenses performed at larger apertures, and I developed techniques to avoid the clinical look digital sometimes can have. I also used a Canon 5D mkII and a pair of speed lenses— 50mm f1.2 and an 85mm f1.2—often at full aperture. Both digital cameras were shot using a tethered set up; with such shallow depth of field, it’s critical to use a laptop to ensure proper focus precisely in the area it needs to be. For the Fuji instant film, I resurrected an old Polaroid 110a that had been converted to take 3x4 pack film, especially for playing with compositional ideas and going after first impressions. I used both the color FP-100c and the fast black-and-white FP-3000b. I also saved all of the negative portions of the peel-apart for later scanning, working through variations on digital until we were satisfied that the best options had been explored.

Suit jacket worn by John Krill, 1967/68. Take Six Boutique, retailer, London. Wool plain weave. Gift of John Krill 2012.22.

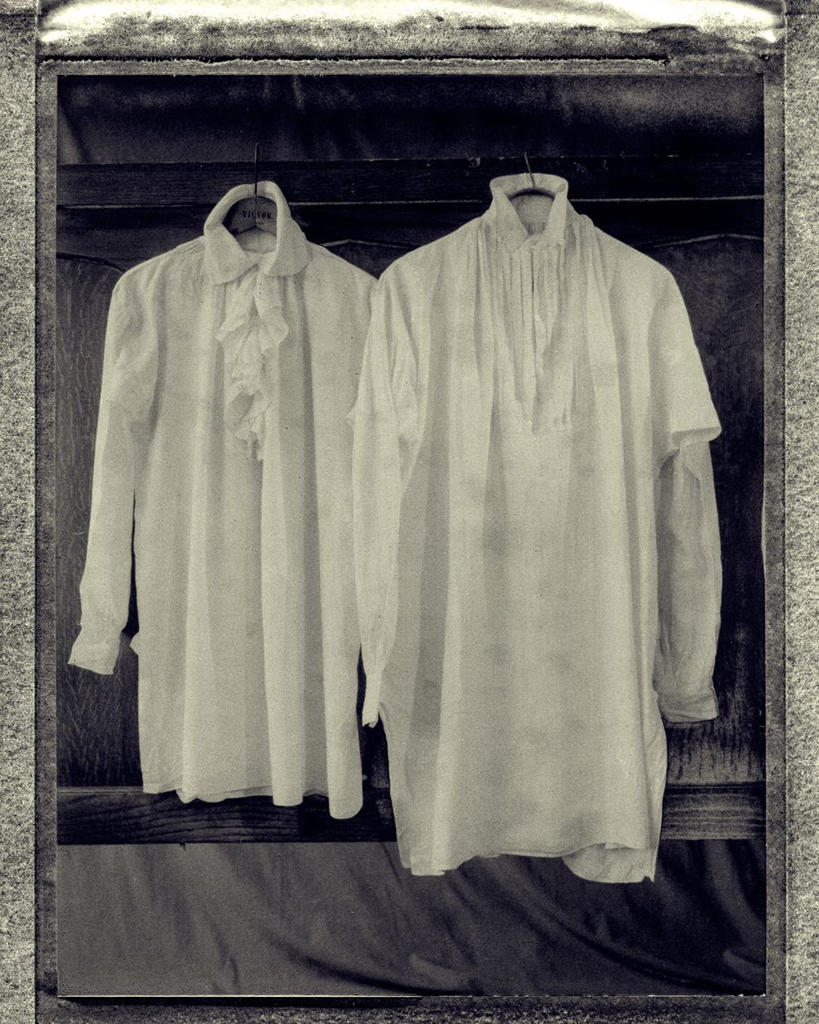

Shirt worn by Joseph V. Crawford, mid-18th century. American. Linen plain weave. Gift of the estate of Margarethe L. Dwight 66.016.21B.

Shirt, ca. 1850. American. Embroidered linen plain weave. Gift of Mrs. Ralph P.Mitchell 45.028.

Shirt worn by Joseph V. Crawford, mid-18th century. American. Linen plain weave. Gift of the estate of Margarethe L. Dwight 66.016.21A.

Shirt, late-18th century. American. Linen plain weave with cotton ruffle. Gift of Mrs. Guy Lowell 43.386.

Shirt, ca. 1850. American. Embroidered linen plain weave. Gift of Mrs. Ralph P.Mitchell 45.028.

Shirt worn by Joseph V. Crawford, mid-18th century. American. Linen plain weave. Gift of the estate of Margarethe L. Dwight 66.016.21B.

Finally, if the set-up seemed right, I worked with a third or fourth “look,” this time on film. From the start, we wanted to work in a more extreme funky lens, with selective-focus mode for particular objects. I accomplished this by going to my personal kit and bringing in a Speed Graphic mounted with an Aero Ektar (the so-called Burnett combo) and a Graflex Series D SLR. The Graflex was mounted with either a Cooke 165mm f2.5 or a Dallmeyer f2.9 Pentac lens. For film I shot Fuji Astia in 4x5. Just like the old days, I boxed up the film each day and shipped it off to the lab. The days of three-hour E6 turnaround are long gone in Providence, so the film went off to Color Services in Needham, MA. The film was scanned on a Hasselblad Flextight scanner when it came back from the lab, so those images could get into the mix as soon as possible. I joked with the curators that I was channeling photographers from the distant past, but in a real sense I was channeling myself from the pre-digital days, and my creativity was re-energized by connecting again with the older methods. Technology is great, but it’s good to step away from it sometimes.

Detail of vest and trousers of three-piece suit worn by Richard Merkin. F. L. Dunne and Company, tailor, New York and Boston, est. ca. 1910. Wool twill weave. Gift of Richard Merkin 1999.65.7.

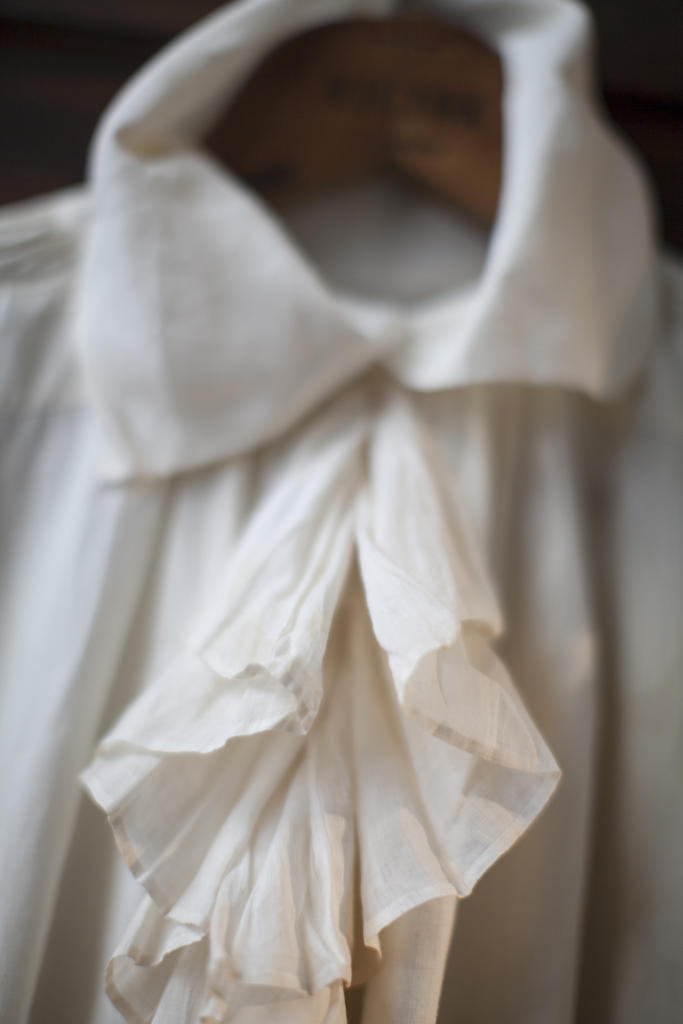

Detail of shirt worn by Joseph V. Crawford, mid-18th century. American. Linen plain weave. Gift of the estate of Margarethe L. Dwight 66.016.21A.

Looking through the camera ground glass at a detail of jacket worn by William Fitzhugh Whitehouse, Jr., 1900/05. Hoar & Co., tailor, Bombay. Cotton plain weave. Gift of the Whitehouse estate 58.160.13.

Erik Gould

Museum Photographer