Eastman Johnson was raised in Maine in a family of eight children, and as a young teenager was employed as a dry goods clerk. When he was about 15, he traveled to Boston and worked in the lithography shop of J. H. Bufford, where he was exposed to techniques that improved his boyhood aptitude for drawing. When Johnson returned to Maine a few years later, he was proficient at making portraits from life in pencil, crayon, charcoal, and chalk.1

With the intention of assembling a portfolio of portraits of eminent Americans, Johnson moved to Washington, D.C., around 1845. There he set up a studio in a Senate committee room, where he depicted such notable citizens as John Quincy Adams, Dolley Madison, and Daniel Webster. When Johnson returned to Boston in 1846, he had added pastels to his technical repertoire and attracted new sitters among members of the intellectual elite, but his career advancement was stalled by limited opportunities to study painting in Boston. In 1849 he and his friend George H. Hall departed to seek instruction in Düsseldorf, where Johnson studied anatomical drawing and portrait painting in oils. By 1851, he was active in the atelier of Emanuel Leutze, where he advanced his skills at narrative painting while working on a replica of that artist’s Washington Crossing the Delaware.2 He remained abroad for five more years, settling next in The Hague and developing a deep admiration for Rembrandt. His final instructional stage before returning to the United States in 1856 was in the Paris studio of Thomas Couture.3

Fortified by Düsseldorf’s narrative tradition, by study of the great collections of Europe, and by exposure to the techniques of one of the most advanced painting studios in Paris, Johnson established himself as a leading American painter. In the late 1850s he set up a studio in New York and was elected to the National Academy of Design. Over the next two decades his career flourished, distinguished by themes ranging from Negro Life at the South4 to studies of maple-sugar camps in Maine5 and cranberry harvest scenes in Massachusetts. In 1870, following the birth of his only child, Ethel, Johnson’s family began to vacation on the island of Nantucket. Here and in Kennebunkport, Maine, where his sister’s family summered, he was provided with ready models for themes of childhood.6

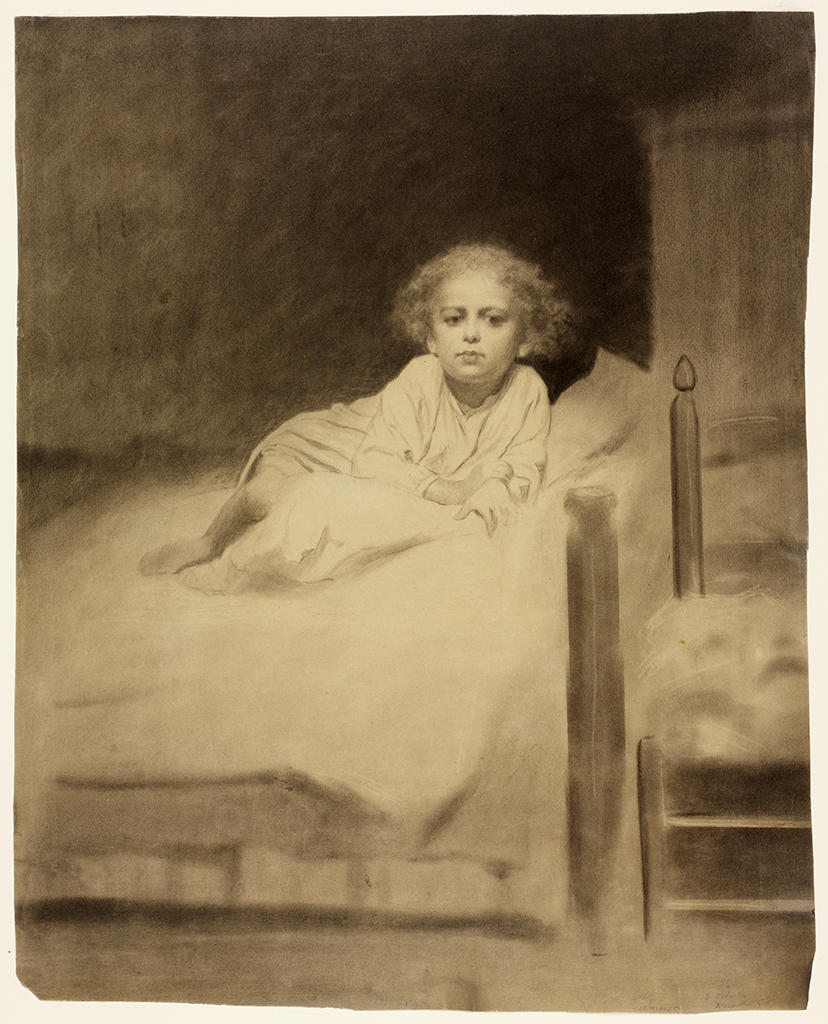

In Child in Bed, Johnson’s reputation as the “American Rembrandt” may be witnessed in his use of chiaroscuro, the masterful rendering of the face, and the softening of details of the figure and setting. Concentrating on the child’s head, he sculpts the eyes and chin with deep shadows and relies on the brightness of the paper to emphasize the nose and brow. The effect of lamplight is suggested by the color of the paper as revealed through black veils of charcoal. By altering the pressure and direction of his medium, scratching through the pigment, and working the texture of the sheet, he coaxes surfaces as varied as cotton bedding and solid wooden furniture. The bed’s simple footboard and the ladder-back chair suggest the interior of a country house, such as those occupied by the Johnson family in either Nantucket or Kennebunkport. With the exception of the basket of clothes on the chair, no attempt is made to introduce picturesque detail or urge a sentimental response. For an artist whose narrative paintings of children had inspired great public and critical enthusiasm, Child in Bedis an intimate and contemplative digression that affirms Johnson’s keen eye for domestic realism.

Landscape and Leisure: 19th-Century American Drawings from the Collection is on view at the RISD Museum from March 13 – July 19, 2015.

Maureen O’Brien Curator of Painting and Sculpture

- 1Johnson’s earliest known portraits are charcoal and chalk drawings, Head of a Woman and Head of a Man, dated July 1844, in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum of Art, and illustrated in Patricia Hills, Eastman Johnson, Whitney Museum of American Art, 1972, p. 6.

- 2This painting, completed in 1851, is in the collection of Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/11417 As the original version had been destroyed a studio fire the previous year, this second large version of this painting was then underway. Johnson worked with Leutze on a smaller replica, oil on canvas, 40 ½ x 68 in., now part of the Manoogian Collection.

- 3Couture promoted painterly technique that preserved the liveliness of the original sketch. Edouard Manet studied with Couture, as did the Boston painter William Morris Hunt.

- 4 In particular, see Johnson’s Negro Life at the South (1859, New-York Historical Society). Originally exhibited at the National Academy of Design in New York under this title, the painting was later known as Old Kentucky Home, after Stephen Foster’s popular song.

- 5Johnson returned to the maple-sugar camps in Fryeburg, Maine, in the spring months of the early 1860s. The RISD Museum’s Sugaring Off, ca. 1861–1866 (45.050), is a large unfinished version of activities at a maple-sugar camp. See Patricia C. F. Mandel’s discussion of this painting in RISD Museum’s Selection VII: American Paintings from the Museum’s Collection, 1800-1930, 1977, 158–63; and in Brian T. Allen, Sugaring Off: The Maple Sugar Paintings of Eastman Johnson, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Museum, 2004.

- 6This includes paintings such as Bo-Peep (The Peep), 1872, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth. https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/u/0/asset-viewer/bo-peep/AwEeJtUNL6Bd1w?hl=en. A gathering of children on the beams of a hayloft is depicted in Barn Swallows, 1878, Philadelphia Museum of Art, one of several works he painted at this time that show children playing in a hayloft. http://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/54178.html