For many of us, a line is the first mark we make. It is a huge developmental milestone when a young child’s first scribbles are set to the page (or wall!), an experience that attunes them to cause and effect and acquaints them with their capacity for hand-eye coordination. Once we start to grow however, the joy of scribbles on the page fade as we feel a pressure for those lines to represent a reality that we see in the world. That pressure to represent can grow so strong, many children learn at a very early age to abandon any creative expression that falls short of realistic representation.

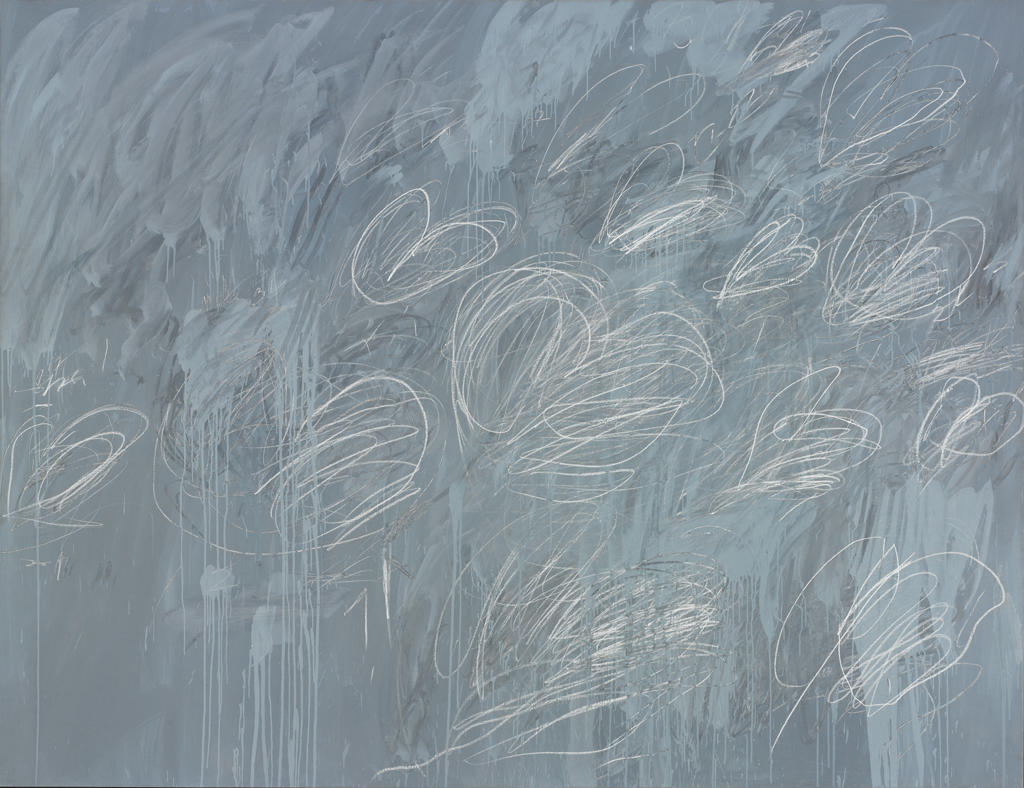

My line is childlike but not childish. It is very difficult to fake … to get that quality you need to project yourself into the child’s line. It has to be felt.

– Cy Twombly

There are many artists, however, who dedicate much of their practice to exploring the power of line. Pat Steir, whose paintings and drawings were presented in a retrospective at the RISD Museum in 2010, examines line as a fundamental effort to communicate. She has said that her work “shows something we all have in us, something that belongs to all of us but is obscured by our habitual way of seeing.” Artist Cy Twombly speaks to the expressive power of a line, but only when it is imbued with feeling. In his untitled painting above, on view in the Museum, Twombly creates a line that appears impermanent and spontaneous, evoking chalk scribbles on a blackboard expertly rendered in oil paint. When he says the line one must “project themselves into the child’s line,” it is to say that one must go back to those first lines, the lines that are free to express without the pressure of representation.

STUDIO PROJECT: Line Timeline

A very simple but successful studio project we’ve done here at the RISD Museum involves using line to express the felt passage of time. This project is wonderful both for children and young adults, and always results in great discussions. Start with a letter-sized piece of paper. Whatever you have is fine (including copier paper) but a heavier weight is nice to work with. Cut two-inch strips down the long side of the paper. Every artist (including parents or caregivers) gets one strip of paper and a pencil.

The strip of paper represents a period of time — maybe from the morning of one day to that night, or for older children, from the beginning of this year until today. Thinking of the strip of paper as a timeline, invite your artist to show their day or year thusfar through line only. Resist the urge to demonstrate, and instead try to keep it as open-ended as possible. This will lead to lines that are personally expressive.

If your child is having a hard time understanding the project, begin with a game. Together, draw as many different kinds of lines as you can think of, then move on to the project.

One of the best parts is discussing each other’s timelines together afterwards. Ask your child to walk you through their drawing. What do the different lines means? This project can open up great discussions — for example, one 15-year-old boy expressed the highs and lows of his schoolyear using a variety of different lines to show his various states of mind, from stress at the beginning of the year to relief at the end.

Encouraging your children to explore line, and the powerful simplicity it can carry, can help free them from stifling attitudes about what art must be and represent. As artist Paul Klee wistfully stated, a line is simply “a dot that went for a walk.”

Aja Blanc

Associate Educator, Family and Youth Programs