Reinstalling a gallery is exciting because it allows museum staff and visitors alike to recontextualize old objects and see them in a new light. RISD Museum installers have been working this past month to put our Egyptian collection in its new home on the recently restored sixth floor. The centerpieces of this collection are, of course, the coffin and mummy of Nesmin, an Egyptian priest who lived around 2,300 years ago. While Nesmin’s beautiful new case has a set location, the question arose of how to orient his body within the case. Upon entering the gallery, should his head be to the left (south) or the right (north) of the case?

We began looking into Egyptian burial customs and religious beliefs. Nesmin was once a living human being; although we cannot know for sure how he would feel about being in a museum (more on that below), we don’t want to fly in the face of his beliefs or damn his soul for all time. Ancient Egyptians were usually buried on the west bank of the Nile, as the Western Desert was associated with the setting sun and thus death and rebirth. With RISD’s location a whole continent and ocean west of the Nile, we’re all set in that regard. Nesmin’s case is mounted on a north-south axis, so we looked into directionality. In the Predynastic Period (the earliest period of Egyptian [pre]history leading up to the emergence of a unified Egyptian state around 5,000 years ago), the dead were buried on their sides facing west. In the Middle Kingdom (ca. 4,000 years ago), non-royal mummies had wadjet eyes painted on the head-end of their coffins and were oriented north-south, so the deceased could look out on the rising sun in the east. Nesmin, however, lived during the Ptolemaic Period (ca. 2,000 years ago), a time for which our team was unable to find specific information about coffin placement in tombs. This is due to the fact that many Ptolemaic burials were not excavated methodically and the burial assemblages were not recorded. Lacking concrete information about beliefs in Nesmin’s own lifetime, our curator would have to consider other factors.

A museum gallery is a place that teaches and engages visually, and objects in the collection need to work in concert to impart a comprehensive message or theme. This goes beyond selecting objects and making them look good: a curator has to take into account practical considerations. Nesmin and his coffin (particularly his face on the coffin) are the focal point of this new Egyptian gallery, and their position has a major effect on visitor foot-traffic patterns. By orienting his head to the north, it would be very close to a wall. To the south, there is a wider space and a door. Ultimately, the curator decided that having more room for groups to congregate was the top priority, and so Nesmin was laid to rest yet again, this time with his head to the south. From the perspective of Nesmin’s head, the entrance to the gallery perfectly frames an east-facing window in the vestibule; we joked that he just wanted to look outside.

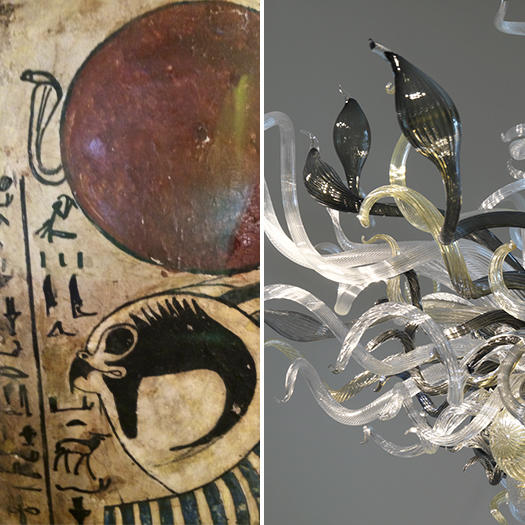

The next day, I noticed something exciting and previously unconsidered about this layout. Nesmin is not just looking out the window, but also at a large chandelier-like sculpture made by RISD’s own Dale Chihuly. This piece, like many of Chihuly’s, features a morass of long glass tentacles. The sculpture’s black tendrils flare out towards the tip, giving them the appearance of erect cobras poised to strike. In ancient Egyptian religion, the cobra was associated with the goddess Wadjet, and with Lower Egypt and kingship. Wadjet is invoked throughout millennia of Egyptian funerary art in the form of the Uraeus, a stylized, upright cobra. Like much of Egyptian funerary iconography, the Uraeus had an apotropaic nature, meaning that it was believed to be able to ward off evil: uraei were thought to spit fire at the enemies of the king or the gods. If Nesmin wanted anything, it wasn’t to look out the window: it was to be reassured by the sight of a nest of giant cobras guarding the threshold to his new burial chamber.

Egyptian funerary rites had two goals: to protect the dead and to ensure their name lived on forever. As part of RISD’s collection, Nesmin’s name is presented to visitors to the gallery and the Museum’s website. Nesmin’s father and grandfather are also in museum collections, but they are exceptions; very few Egyptians from his time period have this type of immortality. Few of the people Nesmin knew have had the afterlife he’s had. Now a museum label and an army of educators keep his name alive, and a swarm of giant cobras and a gorgeous new case keep his body safe.

Jonathan Migliori ( BA, Archaeology and the Ancient World, Medieval Cultures, and Classics, Brown University, 2011, MA Archaeology, University of Durham 2013) is currently an intern in the Ancient Art and Education departments at the RISD Museum and a member of the RISD CE faculty.