Sebastian Ruth has created two environments that offer opportunities to consider how our perceptions of art and the everyday are shaped by context and tradition. In one, a selection of industrial and natural landscapes from the late 19th to early 20th century, bringing the outside into the gallery. These photographs, prints, and a wallpaper length are accompanied by a video created in collaboration with museum staff that captures the cycle of a day over smokestacks accompanied by a new musical composition performed by Ruth. The second environment reconstitutes Warhol’s installation of Windsor chairs, reorganizing how the chairs were stored into an intimate assembly modeled on the tradition of the story circle. This installation asks participants to consider how the traditions that we carry with us shape our experience.

In his contribution to this publication, Ruth’s text reflects on aesthetic witnessing and tradition’s role in our lives by drawing upon the work of educator John Dewey and philosopher Maxine Greene. Readers are invited to participate in aesthetic witnessing through the Ruth’s original composition set to the cycle of a day that unfold over the pulsing smokestack lights. As in the galleries, this experience is interspersed with prompts calling on the reader to practice aesthetic witnessing and meditate on their relationship to tradition.

1.

Smokestacks blinking at night are like guardians over the city. Twenty years ago a friend suggested it would be great to know the musical corollary to the blinking lights episodically going into phase with each other. That idea has been lurking in my mind, and when the invitation for this show came, I realized this was an opportunity.

Aesthetic witnessing: John Dewey talks about restoring continuity between art and the everyday. We tend not to think of everyday moments of focused concentration in the same category as we think of art. He discusses the feeling of total absorption in an activity like gardening, working on a car engine, or preparing a meal, and argues that the focused attention is the same as aesthetic awareness. I began thinking about the resonance between this and the mission of Community MusicWorks (CMW), where a string quartet rehearsing in a storefront on a city street tries to align or coordinate the everyday and the aesthetic.

Restore continuity between the refined and intensified forms of experience that are works of art and the everyday events, doings, and sufferings that are universally recognized to constitute experience.

//John Dewey, From Art as Experience, 1934

Dewey acknowledges that it is problematic that our society normally associates aesthetic expressions with museums, concert halls, and theaters. He talks also about misalignment, considering that many of those places are built to exhibit national pride and rarely push audiences toward aesthetic focused attention.

At CMW, changing how and where musicians do their work is one answer in aligning the everyday and the aesthetic moment. Or arguing they can be one and the same.

In a similar regard, I was led to the smokestacks and the idea that seeing an object that is decidedly industrial and not an art object could be another cognitive merging. As the designer Paolo Cardini said to me when I described the project, “Hearing the lights on the smokestacks as musical would cause me to look for music in other parts of the city infrastructure.”

While standing in a museum, we might see something ordinary as an aesthetic object. How might this cause a viewer to go back outside the museum and see the world as filled with aesthetic potential? This could be the movement of a fire truck down the street, the interaction of a tree blowing in the wind with the spokes of a tire going past, streetlights popping on at dusk.

I have made a soundtrack to the smokestacks starting their night shift at sunset, finishing at sunrise. For the two years, since this project started, I have begun to see them as animators of the city: they have a duty at night, and they get to rest during the day. And one of the lights stays for 24 hours while its friends get to sleep during the day.

The soundtrack is available to you on the digital platform, so that you might listen on headphones while you are looking at the smokestacks in Providence, standing on a street corner near your home, or waiting in line for a coffee. It is intended to be a soundtrack to our observations of the prosaic moments around us, that they might become aesthetic witnessing moments instead.

—

Prompts

For guided aesthetic witnessing

1.

Set a timer and be still for three minutes.

Listen, watch, smell, feel.

What’s inside your mind?

What’s going on outside?

Pay attention to what you notice.

2.

Listen for a bird.

When you hear one,

pay attention to where the sound goes.

3.

Look at a parking lot

or a garbage can for a minute.

Notice what it's doing.

4.

Stay still and watch anything that's moving.

What is its soundtrack?

5.

Set a timer for two minutes and breathe.

Keep breathing.

Notice what happens in your thoughts.

6.

Watch the light change throughout the day.

Set an alarm on your phone

for four different times.

Look at the sky each time the alarm goes off.

2.

For the chairs gallery, I asked Jessie Montgomery—a wonderful violinist and composer and a former CMW colleague—to collaborate with me to create a piece that I would record. We quickly decided to create an improvisation together based on the exhibit.

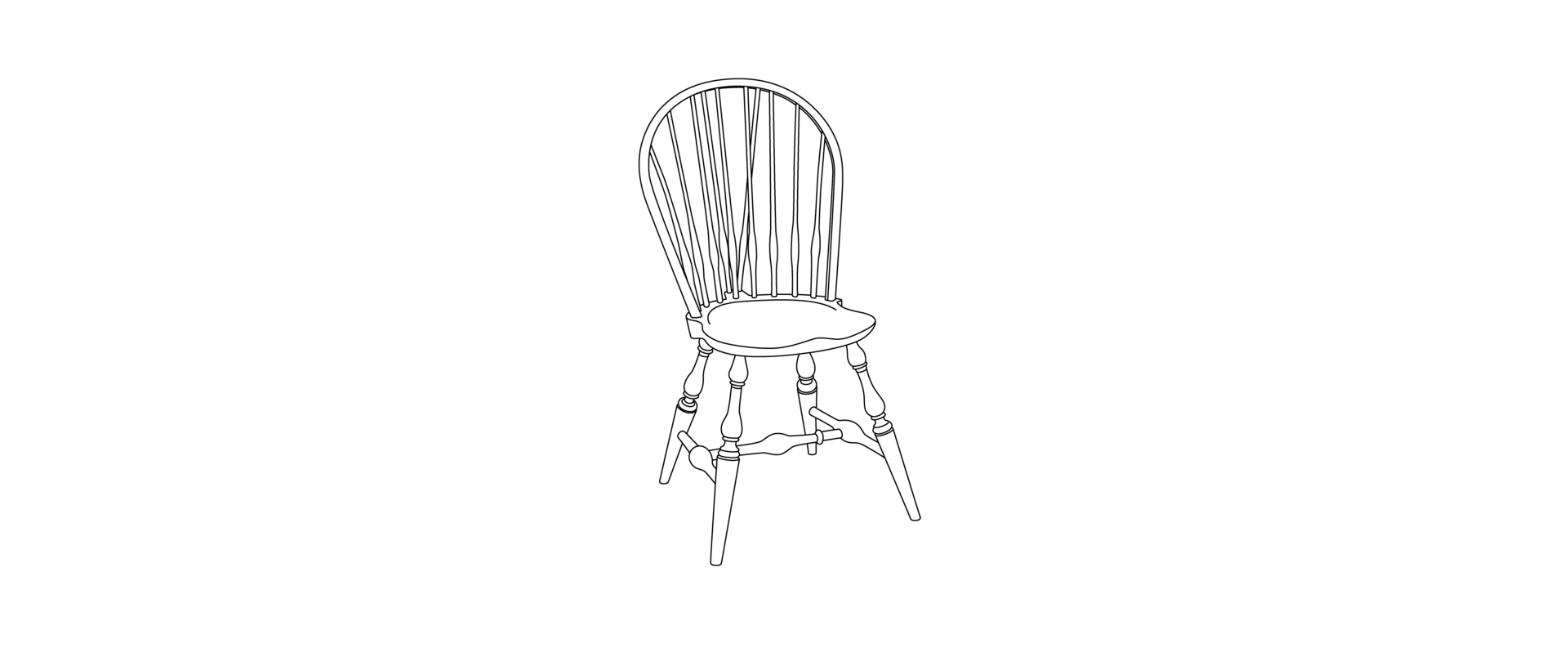

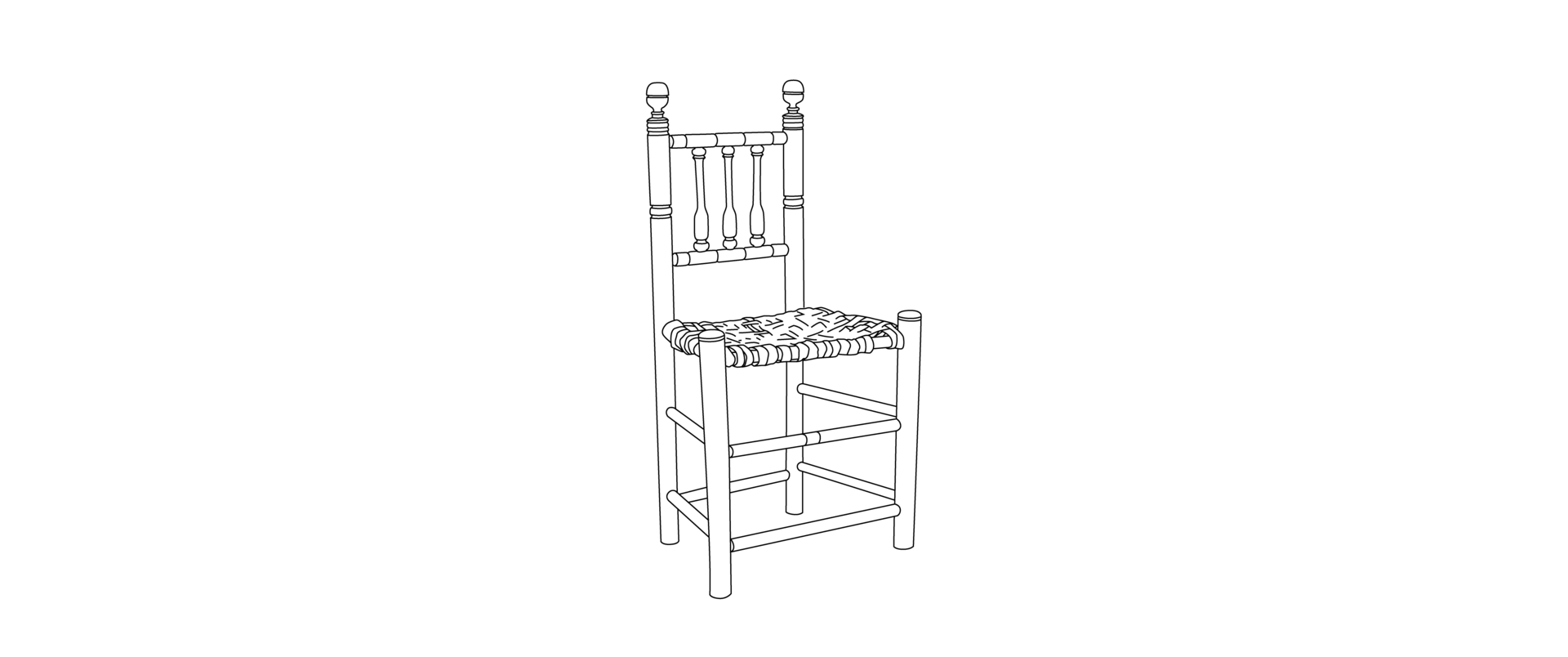

What music corresponds to this gesture Warhol created 50 years ago? In our discussions, we came to the idea that what was whimsical for Warhol—seeing chairs in storage and re-creating that storage in a gallery—has become a fixed reference point. As we again place chairs in this gallery, questions comes up: What is it to take a whimsical gesture and reenact it? Is that true to the spirit of the original act? Is it adhering to tradition?

I argue for aware engagements with the arts for everyone, so that individuals in this democracy will be less likely to confine themselves to the 'main text,' less likely to coincide forever with what they are.

// Maxine Greene, Releasing the Imagination, 1995

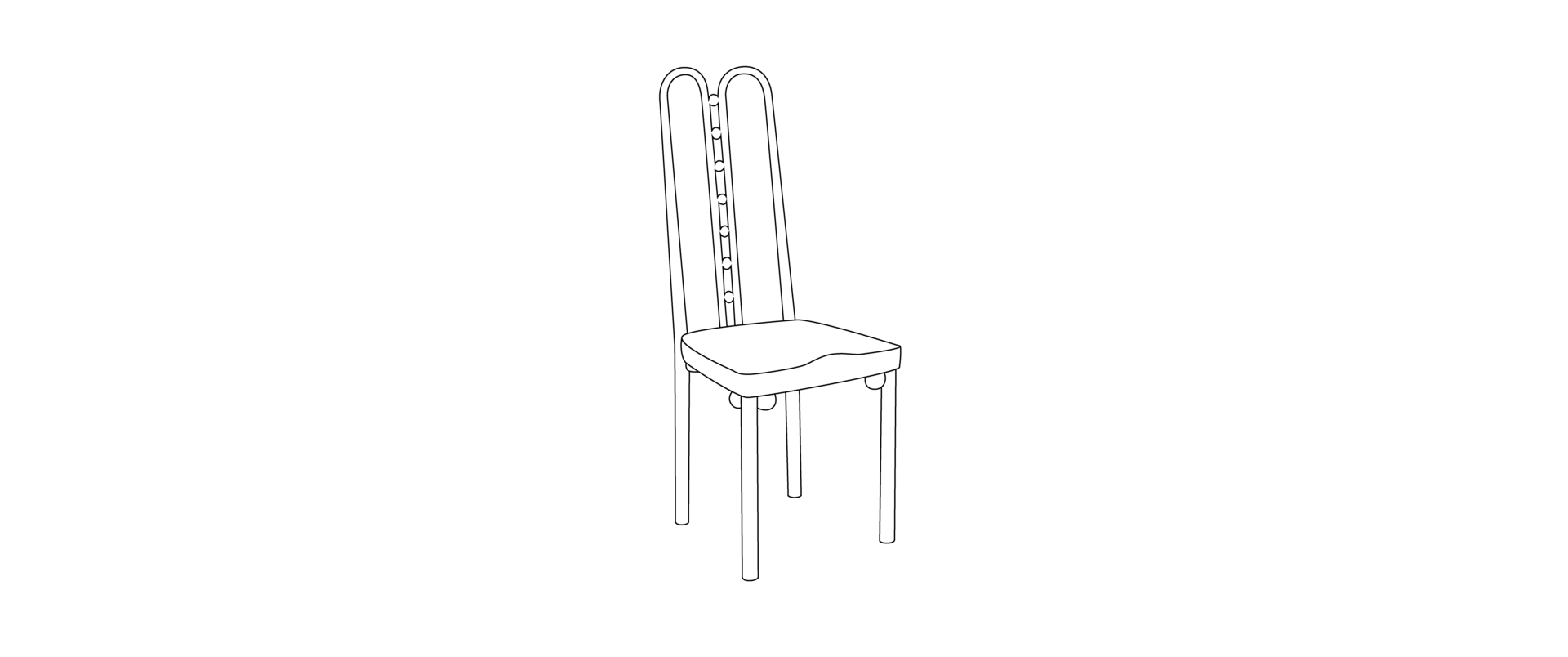

We looked at the chairs in Andy Warhol’s arrangement and asked: What are the people doing in these chairs? What does this array of chairs represent? Is it a waiting room? Is it an orchestra? Then we came to the idea of keeping the basic form of the chairs but rearranging them, suggesting a circle of people talking. Jessie’s mother, Robbie McCauley, herself a celebrated theater artist, taught the story-circle tradition to many of us over the years, reenacting what theater activist John O’Neal and others made in the civil rights movement. With O’Neal’s passing in 2019, it seemed fitting to honor him with this configuration. A group of us would enact a story circle and then create music that supported those voices.

Andy Warhol's original installation of chairs.

The subject of the stories? The role of tradition in our lives. When is it something that propels us? When is it something that holds us back? How do we innovate? When do we follow tradition, and when do we break from it? When is repeating traditions a gift, and when is it a burden? When is it liberating, and when is it constraining?

These questions are musical ones as well. When we play music that was written long ago, we have a dual obligation: to follow the text and re-create it faithfully, i.e., following tradition. But to honor the spirit of the music, we also have an obligation to breathe fresh fire into it.

That is our intent with Warhol’s chairs: reenact yet reinterpret, and breathe fresh life.

In the gallery, we invite participants to contribute to the conversation by stepping up to the microphone and adding thoughts to the soundscape. Participants outside the museum are invited to consider the same questions: What traditions are you carrying on? Which ones are you breaking from? How do you hold tradition in your life?

—

Prompts

For considering the role of tradition in your life

1.

What traditions are you carrying on?

2.

What traditions are you breaking from?

3.

How do you continue to hold tradition in your life?

4.

What traditions are you carrying on unconsciously?

5.

Arrange a circle of chairs.

Conduct a story circle with friends or strangers.

Ask a question that matters to you

and listen to the answers.

Cite this article as

Chicago Style

MLA Style

Shareable Link

Copy this page's URL to your clipboard.

Created under the direction of Sebastian Ruth, this chapter accompanies the exhibition Raid the Icebox Now with Sebastian Ruth: Witnessing, on view at the RISD Museum September 13, 2019–July 26, 2020. Creative direction by Carolyn Gennari. Curatorial support by Sarah Ganz Blythe. Design and illustrations by Carson Evans. Additional production support by Erik Gould and Jeremy Radtke. Jim Moses served as the recording engineer.