When we engage in the process of exhibiting modern and contemporary art, we tend to revert to conventions given to us from the first part of the twentieth century—including the idea of imagining a “neutral” white box space where art could be isolated for our senses, free of outside interference, and arguably experienced in a pure form. What we don’t often think about is that this supposedly “pure” exhibition state rarely exists in daily life: we do not typically live in white cubes, and if we have art at home this has to rather conform to our living environment instead of the other way around. Furthermore, seeing art in the context of someone’s home can be very revealing and often telling of the life and ideas of the individual who once owned those art works. Their placement in particular locations of the house and their coexistence with utilitarian objects tell us a very different story to the one told in the white walls of the museum. And as we try to learn about the world of an artist, learning about the environment where they live and work can help us gain new insights about them, no longer as abstract historical figures, but as the human beings they are.

Inventarios/Inventories is an exhibition for the RISD Museum that considers the “domestic life” of artworks. This museum is a particularly meaningful place to do such exploration given the importance of its period rooms in the institution, which seek to tell us about the private lives of those who lived in the past.

In this chapter we have aimed to share some of those personal stories with you. Included also are a couple earlier texts I have written that consider the role that constructed environments play in conceptual artistic practices and how we can learn about historic museums from the standpoint of art.

Visit with

Milagros de la Torre

Peruvian artist Milagros de la Torre (b. 1965) currently lives in New York. She has worked in photography since the early 1990s, making work inspired by historical photographic techniques and vernacular street-photography approaches, which she has incorporated in her own portraiture practice. She often reflects on her personal experience; as part of that process she has at times photographed garments that have a meaning to her or that have a particular symbolic importance. The investigative nature of her process and methods of presentation often make the photographed object look like a piece of evidence.

Milagros de la Torre [left to right] // Sin título (Untitled), 1992 / Photogravure on gampi paper / 2003.45.4 // Sin título (Untitled), 1992 / Photogravure on gampi paper / 2003.45.5

These works belong to a series De la Torre developed in 1992 around garments and the stories they tell. The artist depicted clothing that once belonged to her mother using photogravure, a mechanical process that etches a photographic image onto a plate. Printed in negative form on very thin paper, these ethereal, spectral-like images evoke the ways our household possessions tie us to our families and our ancestors. De la Torre’s representations make me think of a phrase by Stephen Dedalus, the main character in James Joyce’s Ulysses: “—What is a ghost? Stephen said with tingling energy. One who has faded into impalpability through death, through absence, through change of manners.”

Visit with

Luis González Palma

Luis González Palma (b. 1957) is a Guatemalan photographer whose work started gaining prominence in the 1980s. By sometimes tinting his photographs a sepia, almost golden, tone, the artist ascribes a certain historical quality to the images, while at the same time making them appear atemporal. Even though his photographs are often portraits, they function less as personal depictions and more like representations of ideas the artist is trying to convey.

González Palma’s work seems to connect with the history of 19th-century art, in particular with the work of European Symbolist artists such as French painter Odilon Redon. González Palma’s subjects, however, are usually indigenous young women and men. He has often reflected on the subject of the gaze, and his early work presents a number of indigenous subjects in a direct frontal engagement with the viewer. This body of his work questions representation and, to an extent, self-representation. The artist himself has said, “The face [of my subjects] function like a mirror where I see and question myself and where I try to make sense of myself.”

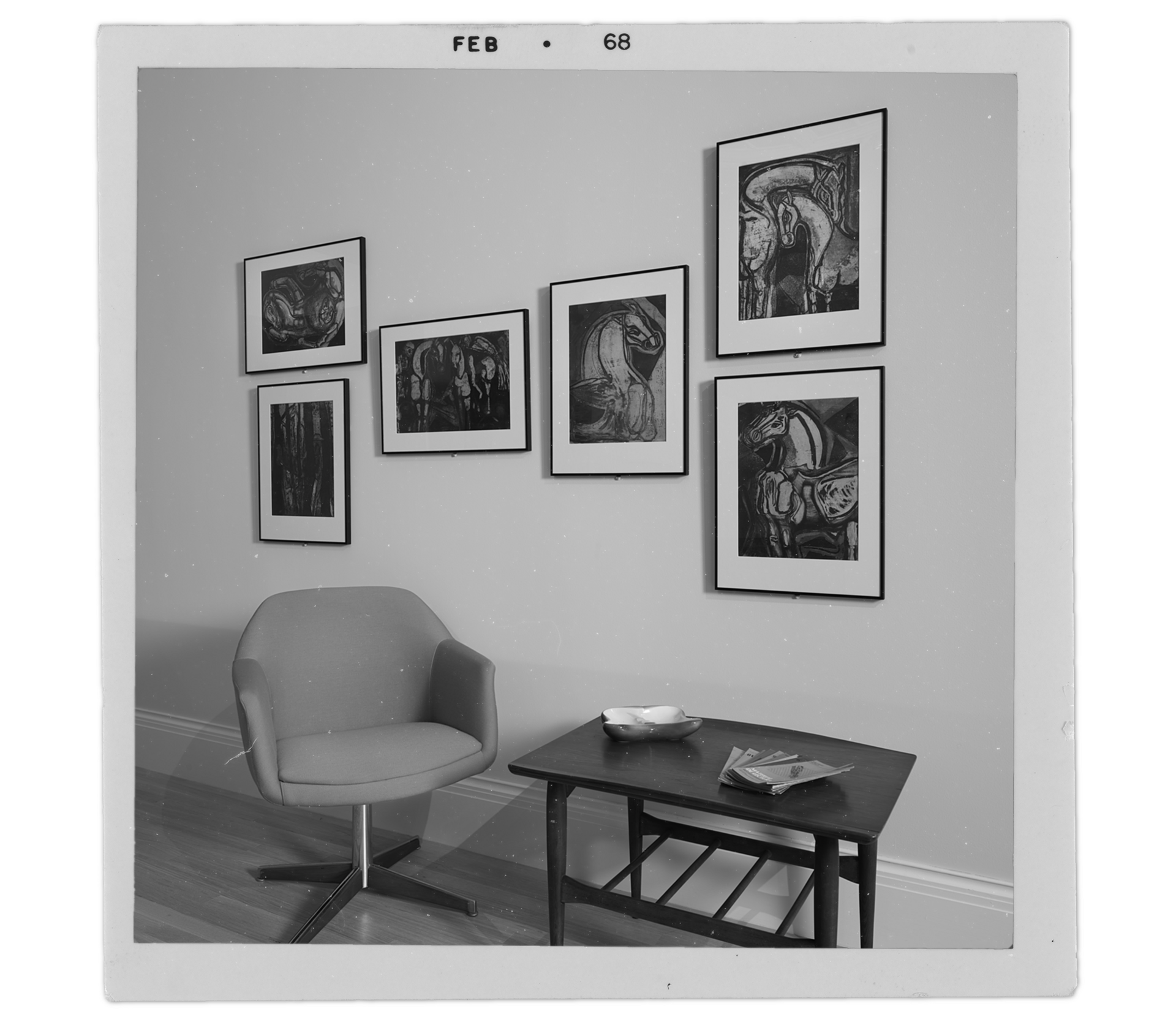

In our recent discussions about a suitable location for these photographs, González Palma imagined a library or a midcentury living room akin to the one where he grew up in Guatemala.

Luis González Palma [left to right] // Sin título (Untitled), ca. 1995 / From the portfolio El circo (The Circus), 1998 / Platinum print / 2014.104.8 // Autorretrato (Self-Portrait), ca. 1995 / Platinum print sewn to mount with thread / 2014.104.16 // Sin título (Untitled), ca. 1995 / From the portfolio El circo (The Circus), 1998 / Platinum print / 2014.104.5

Visit with

Roberto Matta

Chilean artist Roberto Matta (1911–2002) is widely considered one of the most prominent painters of the 20th century, with a body of work that engaged a range of key modern art movements. Like several Latin American artists of his generation, he traveled abroad as a young adult—first to Paris, where he was influenced by Surrealism, and later to the United States, where he was exposed to Abstract Expressionism.

Matta had six children, several of whom also became artists. They include Gordon Matta-Clark (1943–1978) and Ramuntcho Matta (b. 1960), a French producer, sound designer, and visual artist. Ramuntcho collaborated with us for this presentation. With Roberto’s works from the RISD Museum collection, we also show excerpts from a documentary Ramuntcho produced about his father, Intimatta (2011). As its title suggests, the film offers a deeply personal portrait of the painter at home and his studio, sharing reflections about art. Intimatta offers an example of how visual artists live their daily lives with their art in domestic settings.

Roberto Matta / Composición (Composition), 1961–1962 / Oil on canvas / 2001.8

Visit with

Miguel Angel Ríos

Miguel Angel Ríos is an Argentine artist who moved to New York in the 1970s, during the rise of the political dictatorship in his country. His work, which ranges from video to drawing, has always shown concerns about politics and power relationships, national identity, and borders. More specifically, many of his works reflect on the idea of Latin America.

Miguel Angel Ríos / Cono sur (Southern Cone), 1993 / Pleated Cibachrome and oil on canvas, pushpins / 2004.23

In the early 1990s, a time that marked the 500th anniversary of the “discovery” of the Americas, Ríos started creating maps as a reflection on the way in which map-making can be a form of domination. Ríos tears up reproductions of historical maps, rearranging the pieces into a new whole, as seen in Cono Sur. The artist’s act of rearranging and reconfiguring thus becomes a form of symbolic resistance. To illustrate the way he works in his studio, Ríos has placed sections of a work in progress next to Cono Sur.

Visit with

Arnaldo Roche Rabell

Puerto Rican artist Arnaldo Roche Rabell (1955–2018) loomed large in the studios and hallways of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago when I studied there. Reproductions of his luminous paintings were ubiquitous, and professors spoke admiringly of the ways he evoked the tropics and invoked Caribbean identity through neo-Expressionistic brushstrokes and his singular technique. Of his work, the artist once said: “I could not tell you whether part of my conscious or unconscious comes to life in these processes. . . . It is the physical act of painting that . . . ratifies the urgency of my ideas, connecting all the actual elements I rub, print, or project on the canvas. That is when the subconscious is released, materializing itself through digging, pasting, and tracing.”

It was a welcome surprise to find Spirit of the Colony in the holdings of the RISD Museum. I contacted Roche Rabell via instant messaging, never having met or spoken to him before, explaining the plans for this exhibition. He replied and expressed interest in participating. Three weeks later, as we continued our conversations, he tragically passed away due to lung cancer.

The inclusion of his work in this exhibition recognizes and pays tribute to an artist who contributed so much to Latin American art.

Arnaldo Roche Rabell / Espíritu de la colonia (Spirit of the Colony), 1993 / Oil on canvas / 1994.026

Visit with

Liliana Porter

Argentine artist Liliana Porter (b. 1941) has lived in New York since 1964. From those early years, she engaged in printmaking and in conceptual practices that she pursued through installation and other mediums.

Pleasure in the absurd is an attribute that I highly value in artists. Absurdity is a creative risk, because the presentation of something that does not make sense can be perplexing for a viewer. Porter masters the use of the absurd, embracing it with humor and playfulness but also with great conceptual clarity. Porter’s works in the RISD Museum’s collection involve small toys and figures that she found in flea markets. She creates improbable juxtapositions of these objects, inviting the viewer to invent stories or make connections between them. Porter’s subjects are often inexpensive souvenirs, small ceramic ornaments, objects that might be referred to as kitsch, vernacular items of a religious nature, or wind-up toys she finds entertaining. Looking at these objects, I sense a great deal of nostalgia, often thinking of the knickknacks in my aunt’s apartment in Mexico City and how they functioned as souvenirs of her many travels. I also think of my own childhood, and the various toys that I once had that now are gone. Porter recruits her objects as actors in her absurdist plays, which often take the form of photographs, prints, and even videos. More recently, she has worked in performance art, working with actors to recreate scenes similar to these.

Liliana Porter [left to right] // 10:08 A.M., 2001 / Lithograph and drypoint on paper / 2002.52.3 // Para ti (For You), 2001 / Lithograph and drypoint on paper / 2002.52.1 // La conversación (The Conversation), 2001 / Lithograph and drypoint on paper / 2002.52.2 // La Oferta (The Offering), 2001 / Lithograph, drypoint, and collage on paper / 2002.52.4

In her artist studio in Rhinebeck, New York, Porter holds a vast collection of these objects, many of which have figured in her series. In dialogue for this exhibition, she and I decided to show some of the original objects she employed to create works in the RISD collection, as well as other objects that have inspired her.

Visit with

Alfredo Castañeda

I first saw reproductions of the works of Alfredo Castañeda (1938–2010) as a teenager in Mexico City, where Castañeda was born. His images haunted me: like a lot of Surrealist art, their dream-like quality tied directly with the poetry of Mexican writers of the 1930 and 1940s I admired, such as Xavier Villaurrutia.

Castañeda often portrayed himself, making his works acquire an oblique biographic narrative. He juxtaposed these realistic portraits with unusual landscapes, creating an enigmatic and sometimes discomforting or eerie environment. Like other painters of the Surrealist period in Mexico, such as Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo, there often is a mystical quality to Castañeda’s representations that is heightened by their titles.

A latecomer to Surrealism and an artist who became active at a time when these practices were already being overshadowed by conceptual and process-based art, Castañeda is often overlooked. However, he is an important representative of a period when a number of Mexican artists pursued deep psychological explorations of the self and of symbolic imagery that could lend itself to multiple poetic readings.

Alfredo Casteñada / Antiguo recuerdo (Old Memory), 1972 / Oil and photograph on Masonite / 72.107

Visit with

Delia del Carril

One of the strengths of the Nancy Sayles Day Collection at the RISD Museum lies in Latin American printmaking, and the work of the Argentine Chilean artist Delia del Carril (1884–1989) stands out in particular. Del Carril’s life story is too often, and unfairly, tied exclusively to her relationship with the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda. Recognition for her extensive body of artwork is overdue.

Born to an aristocratic family in Argentina, Del Carril also lived in Paris, Madrid, and Santiago, which eventually became her adoptive home. Although she made art throughout her life (she had studied with Fernand Léger, amongst others), she did not dedicate herself fully to artmaking until 1959, when she was in her seventies, and had her first solo exhibition in 1961 in Santiago.

Delia del Carril [lower left, clockwise, From the portfolio Seis grabados originales (Six Original Engravings)] // La noche (The Night), 1965 / Engraving and aquatint on paper / 71.027.6 // La señora yegua (The Madam Mare), 1965 / Engraving and aquatint on paper / 71.027.3 // Del apocalipsis (Of the Apocalypse), 1965 / Engraving and aquatint on paper / 71.027.4 // Equinoccio I (Epoca del año en que el día es igual a la noche) (Equinox I [Time of the Year that Day Is Equal to Night]), 1965 / Engraving and aquatint on paper / 71.027.1 // El caballo y la caballita (The Male Horse and the Little Female Horse), 1965 / Engraving and aquatint on paper / 71.027.5 // Equinoccio II (Equinox II), 1965 / Engraving and aquatint on paper / 71.027.2

Del Carril is known for experimenting with various printmaking techniques and for her thick trace of figures, particularly of horses, for whom she had a personal affinity. Referred to as “a flower of unbreakable stem” by the Spanish artist and poet Rafael Alberti, Del Carril died in Santiago at the age of 104. She bequeathed her home to Chile’s Communist Party, who converted it into a museum that bears her name and holds a substantial group of her works.

1.

Polyvalent Spaces

The Postmodern Wunderkammer

and the Return of Ambiguity

1.

Sometime in 1987, on a modest block of Venice Boulevard in downtown Culver City, west of Los Angeles, the Museum of Jurassic Technology (MJT) quietly opened its doors to the public. The project, the creation of an unassuming man named David Wilson, presents viewers an immersive, exquisitely installed Victorian-era museum environment full of dimly lit dioramas and exhibitions. These theatrical displays offer a wide variety of natural and historical oddities that narrate what Wilson defines as “the Lower Jurassic,” ranging from horned ants and Flemish moths to microscopic sculptures made out of human hair and representations of old-time remedies. The MJT recurs to obscure chapters of human knowledge, resulting in a Borgesian universe of poetic and cosmic connections and guiding us, as the museum itself claims, “as a chain of flowers into the mysteries of life.” The museum’s perplexing exhibits, with their elaborate narratives, beautiful presentation, and, to many, suspicious veracity have generated an enthusiastic cult-like following amongst contemporary artists, taking a unique spot as an “artist’s Wunderkammer.”

A second example of a contemporary Wunderkammern—this one on the East Coast and taking art history as its subject—is located in a rear building near the corner of Spring and Mulberry streets in New York’s SoHo. Opened to the public in 1992 and still in operation, The Salon de Fleurus doesn’t have a web page, nor does it advertise itself through any means. Instead, it has existed mainly by word of mouth for two decades in Manhattan, and its hidden feel is vital to its own anachronistic condition, as it references a historical period far before the digital age. The Salon is open only in the evening hours—I was told this was done in order to give a certain quality to the experience. I will not describe the interior in detail, so as not to disrupt the potential experience of the reader in visiting the site, but suffice it to say the name relates to Gertrude Stein’s Paris apartment at 27 rue de Fleurus, where she held what was likely the very first collection of modern art. This evocative environment, Édith Piaf album playing in the background, oscillates between the domestic and the public space, or between an antiques bazaar and a museum. Several paintings that hang on the dim-lit walls are described as the work of “anonymous authors,” but they appear to be replicas of works by Cézanne, Braque, and Picasso. Together, they conjure up the defining yet fragile moment in history when these pieces were hanging for the first time in history. Visitors to the Salon (the Salon only admits a very small group of people at a time) are welcomed at the door by a host who describes himself only as the “caretaker” of the collection.1 He conducts the group to the rear of the building and, after entering the Salon and letting the visitors take it all in, he starts with a narration that further positions the space as a perfect hybrid of a historic house and a mythical place—namely, the birthplace of Modernism.

I will argue that the slipperiness, of these projects, achieved through a delicate choreography of physical and conceptual space, has become one of the most important contributions to rethinking today’s artist enterprises, merging earnestness with irony, certainty with self-doubt.

2.

Because neither Wilson nor the Salon organizers themselves claim their spaces as art projects or describe themselves as artists, these don’t seem to be accurate labels to apply to either of them. Yet the pedagogic license taken over the interpretation of the objects, the opaque mission statements of their enterprises, and the unusual conditions of the exhibitions also would prevent us from placing them on the roster of Los Angeles or New York cultural institutions. Wilson’s decidedly ambiguous positioning of his museum has made it, for the most part, impossible to extract from its original environment and insert into a traditional art-historical narrative. A case in point would be a casual conversation I had on the subject in 1999 with MoMA’s curator Kynaston McShine, who had just opened his exhibition The Museum as Muse—MoMA’s attempt to document and chronicle both the institutional critique generation and the Postmodern impulse by artists to use museums as their subject matter. When I inquired about the conspicuous absence of the MJT in MoMA’s exhibition, McShine shrugged: “I just didn’t know how to fit the Jurassic into the show.” A similar problem arose when curator Larry Rinder selected the Salon de Fleurus to be part of the 2002 Whitney Biennial. While some objects from the Salon were placed in the galleries, they felt out of place inside an art museum. The effect of being inside the Salon was impossible to recreate and the true experience was left for only the scheduled visitors to the actual location.

McShine and Rinder are not the only ones who have had trouble pinning down these Postmodern Wunderkammern—like the MJT’s conceptually elusive Flemish moths—in art history. The constant conundrum of how to place these projects in a curatorial context—what is true (or not true) about the exhibits, whether these should be regarded as artworks or not, whether the organizing institutions should be treated like any other museum, and so forth—is also the main reason for their success and might suggest that they may actually be all these things at once. It was the late curator Marcia Tucker who first gave the most accurate assessment of the MJT: “It’s like a museum, a critique of museums and a celebration of museums,—all rolled into one.”2

Much has been written about the MJT in terms of its history, its exhibitions, and its connection to the traditional cabinet of curiosities—most notably by Lawrence Weschler in his 1995 book Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder—so I will not repeat Weschler’s insightful description and analysis. What I will offer in this short text is are some thoughts on where contemporary Wunderkammern like the MJT and the Salon de Fleurus could be placed in the larger historical context of contemporary art practice, tracing a brief typology of these projects and their spatial and narrative strategies and arguing how the manipulation of spatial, cognitive and narrative conventions proposes models that in fact are now helping redefine the notion of the alternative space employing, in an unorthodox way, community-building notions that are comparable to Ray Oldenburg’s theory of the “third place.” I will argue that the slipperiness of these projects, achieved through a delicate choreography of physical and conceptual space, has become one of the most important contributions to rethinking today’s artist enterprises, merging earnestness with irony, certainty with self-doubt.

3.

One of the great gifts that Postmodernism brought in the visual arts was, via Minimalism, the appropriation of historical models through the filters of irony and self-awareness. This was common of artists’ insertions into institutional frameworks roughly from the 1970s to the ’90s (as seen in the work of Michael Asher, Fred Wilson, Hans Haacke, Barbara Bloom, Andrea Fraser, and many others) and became associated with institutional critique. These artists used the theatrical and pedagogical conventions of museums as a medium to build a phenomenology of the viewer and increase awareness, self-reflexivity, and critical thought on issues such as the authoritative voice of the museum, the subjective narratives of art history, and the alignment of cultural institutions with economic and political power. The more ancillary practice by artists to concoct museums as critical and autonomous mechanisms could be traced back to the inauguration in 1968 of Marcel Broodthaers’s Musée d’Art Moderne, Départment des Aigles. By creating a conceptual and nomadic museum without a permanent collection, Broodthaers’ project displayed the self-consciousness, irony, confrontation, and mutability that became the basis of institutional critique. Broodthaers’s fictional museum model, as well as the later works by artists who took on the institutional disguise, were more than an atavistic simulation: it was a reappropriation of the experiential ritual of art, a criticism of the purported knowledge onto which Modernism laid its foundation and an attempt to blur the boundaries of art and life and historical and fictional narratives.

These types of hybrid “museums” adopt a museological narrative model that from the onset counters the rational linearity of Modernism and rebels against its pristine ideals of neutral space. In terms of space, it is natural that, because the canonical Modernist narrative in the visual arts had been staged using the white cube, that its counterpoint should be constructed using an opposite device. In the case of the Salon, there is an attempt to re-enact the pre-Modern environment that led to the construction of the white cube: the domestic space where artists socialized, exchanged ideas, and lived their lives. Similarly, the MJT appropriates elements of the entire history of museums, ranging from the seventeenth-century cabinets of curiosities to the nineteenth-century natural history museum, as if searching for a new historical referent that would altogether bypass the avant-garde.

In terms of narrative linearity, the MJT’s exhibits don’t deal with art necessarily, but rather with curiosities of science and history, returning, as it were, art to an encyclopedic mission, a primal habitat where it once shared space with scientific and religious items, as well as with objects of superstition and wonder, liberating it from the Modernist demand of speaking about itself. The Salon de Fleurus, by presenting replicas of famous paintings that are claimed as anonymous, proposes a questioning of authorship that is not only pre-Modern, but pre–art historical, returning to the time when art in churches had no authors.

What is regained by this strategy of displacement, interestingly, is a more heightened awareness of the visual information being presented to us.

4.

Different and unique as they both are, both the Museum of Jurassic Technology and the Salon de Fleurus employ a strategy of contextual displacement and immersion, in which the viewer has to ask where he or she is. This slight confusion is key to introducing the viewer into a situation where objects and the place itself, despite specific names (this is a museum, that is an exhibit, this is an artwork, you are a museum visitor, etc.,) soon start looking like something else and shedding their officially assigned meaning. This is seen, for example, in the way the MJT’s scientific exhibitions don’t appear to be objective, and in how the Salon doesn’t feel like an anonymous location but rather a very accurate historical reconstruction of a very concrete place and the events around it.) What is regained by this strategy of displacement, interestingly, is a more heightened awareness of the visual information being presented.

Connected to the feeling of displacement is the playful tension that both spaces employ with notions of authenticity and truth as conveyed by an institution. While using formal devices and authoritative interpretive tools such as the ones used by museums, but also presenting statements that are at best dubious or arguable, one is left to wonder, always with more questions about the answers that are being given. The more one scratches for the “truth” of these places, the more one sinks into ambiguity.

Another equally important component of these two spaces is their intimacy. Both the MJT and the Salon are relatively small locations, so the social dynamics that take place are closer to what would take place in a small or medium-size shop than in a public art museum. Size allows also for a more personal relationship with the art, and perhaps for an unexpected kind of isolation where we are not surrounded by others to influence our thoughts on what we are experiencing. We instead reflect on our own and have one-to-one dialogues. Additionally, spaces like these become conversation pieces amongst the initiated, offering a mystery that can be discussed and debated. Amongst those close to the spaces, the humor of deceit becomes important.

It goes without saying that all the above described conditions are very difficult, if not impossible, to recreate in public art museums today. A museum’s public mission and duties regarding access and interpretation and institutional mandates to accommodate large groups of people in every exhibition greatly reduce the possibility of preserving the one-to-one experience of art. In reality, this is the great irony about museums, which in theory should offer viewing situations where the art works come to life in the mind of the viewer. Yet, because the public demands access and information in all sorts of formats, much of the experience needs to be mediated through frames, labels, and explanations that can quickly turn each artwork into a dead specimen. Contemporary Wunderkammern, by contrast, can afford to dispense with any demands of public service and create a world where a seemingly opaque and surreal logic erases every sort of frame—or, rather, the frames that it presents appear to fuse into the work itself. (The mission statement of the MJT, for instance, refrains from explaining anything, becoming an extension of the opacity of the interior space.)

Jean Baudrillard’s quote at the beginning of this essay refers to how the inevitable effect of a perfect simulation is the nostalgia of the real. There is indeed a pervasive sense of longing for these places, a romantic impulse to restore a kind of knowledge that had been lost (or, quoting one of the exhibition titles of the MJT, “no one will ever have the same knowledge again.”) In the Postmodern context, this nostalgic sensibility should not be interpreted as a Pre-Raphaelitesque movement toward recapturing lost innocence or building an artistic Arcadia, but instead as another kind of impulse as described before: the restoration of the viewing experience, and the attainment of secret knowledge, as an alchemical process that bestows the visitor with a prized possession through mysterious means.

5.

Both the MJT and Salon de Fleurus emerged during a period where the global expansion of the art world in post-wall Europe led to a oversize biennial landscape, where major museums focused on blockbuster exhibitions that would attract the larger public, and where incremental rises in the art market, coupled with the decline of public funding for the arts in the United States, led to the closing of many alternative spaces, displacing many artist communities and leaving them in search of spaces for presenting their work. At the same time, in the late ’80s and early ’90s, urban changes in American cities led sociologists to propose new models for neighborhood design and local solutions to community building. In 1989, sociologist Ray Oldenburg famously proposed the notion of the “third place,” that location between work and home where individuals find an environment that is structured so that they can feel at ease but also stimulated enough to engage in activities that reinforce a sense of self and belonging. (This notion was taken, and successfully implemented, by the corporate chain Starbucks, which expanded exponentially in the ’90s by selling the idea of a location that existed between work and home.)

The Oldenburgian third place is grounded on the notion of a participatory public, where the primacy is personal interaction and participants can feel most at ease. In perhaps a counterintuitive way, spaces like the MJT and the Salon de Fleurus propose a version of the third place for the art community: a place for the initiated, where experience of the work takes primacy but simultaneously serves as a social glue. By making it difficult to access, the membership becomes more enthusiastic. Furthermore, I would posit that these third spaces in the visual arts go beyond the normal dualities of work and home: they propose a space between truth and fiction, the museum and the artist studio, public and private, knowing and unknowing. While theoretically grounded in Postmodernism, they are a step beyond traditional oppositionalities, creating a place where viewers by necessity need to adopt simultaneous roles as architects and inhabitants or as curators/narrators and actors. The viewer, in this case, becomes a complicit participant in furthering the dialogue of fiction (that is, by playing along as a regular museum visitor.)

Looking at the new generation of artists and artist spaces in Los Angeles, one could argue that at least in the case of the MJT, its example has been followed by a number of new experiments, if not in museum-building, certainly in ambiguous spaces. Founded in 1994, the Center for Land Use Interpretation describes itself as an “education and research organization,” but it participates directly in the art world through site-specific projects and activities. While it doesn't operate like a museum, Machine Project, a space run by artist Mark Allen, has adopted a hybrid model of community center, Kunsthalle, and school. Artist Fritz Haeg turned his house in Los Angeles into a school, organizing a variety of activities that ranged from basic learning experiences to performance. More spaces emerge on a nearly daily basis. New York has also seen a remarkable proliferation of such hybrid spaces, although due perhaps to the much more higher rents in the city, they also tend to live much briefer lives.

What is clear from the experiment of the Postmodern Wunderkammern is that, drawing from the tools of institutional critique, they emerged as autonomous spaces that refused definition as a key part of their identity, remained small in scale in order to retain individual relationships and experiences, and reached out to a type of knowledge that may be obscure, universal, erudite, or simply strange to produce moments of wonder and communal experience, always through participation in a simulated representation. Their nostalgic aura is yet another of their disguises: they are as much about the present as they are about the past. They point to a need to abandon permanent structures and move—as we already do in so many phases of our contemporary lives—into movable platforms of experience.

- The Salon de Fleurus was still in operation when this essay was first published. It subsequently ended, as described here, in 2014. Additionally, out of respect to the integrity of this project, I refrain from mentioning the name of the author (or authors) of the Salon de Fleurus.

- Quoted by Lawrence Weschler, in Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder: Pronged Ants, Horned Humans, Mice on Toast, and Other Marvels of Jurassic Technology, (New York: Vintage Books, 1995), p. 40.

2.

On Artistic Historicism

1. Foyer: Contemporary Art and Historic Sites

A few years ago, I visited the House of the Seven Gables, the eighteenth-century building in Salem, Massachusetts, that Nathaniel Hawthorne used as his inspiration for his legendary novel. I had been looking forward to that moment for some time, eagerly expecting to be transported into the strange and fascinating past of New England.

Unfortunately, though, as is the case of many historic buildings, the only way to visit the site is by following a tour guide, and the woman who became our Virgil in this enterprise looked pretty unexcited about her job. She had evidently done the tour a thousand times, and we clearly were just one more tired round (and the last one for the day, which clearly made the matters worse.) I felt bad for her, and also for myself, since we both had to go through something we didn’t want to do to get what we wanted (me, to see the site, she, to get paid.) She ran through dates and names one after another, explaining terms and preempting questions and comments that surely had been asked in the past by previous visitors—and which we would perhaps have asked had we be given a minute to reflect. With her glassy eyes and monotone voice, she was pretty much a living and moving museum label.

Then there is the opposite kind of approach, which I have often seen in Mexico and, most delightfully, at archaeological sites, the tours offered by unofficial local guides to unsuspecting tourists. In this variety, historical truth is usually taken liberally and often completely thrown out the window as we hear guides to tell incredible stories about jaguar priests and moon goddesses and their improbable relationship to the temples or grounds where one is standing. This kind of tour is like storytelling in progress, as you can often detect that the tour guide has been refining and inserting new details based not on historical accuracy but on what elements of the story would be most impressive to a Swedish teenage backpacker. Did the Aztecs eat the hearts after the sacrifice? Did they play ball with them? The pre-Columbian world is a perfect scenario for these kind of tours, because we know so little about so much of it that it would be impossible to ascertain the truth or fantasy of whatever a tour guide is telling us. While this is certainly on the other end of the spectrum of historical accuracy, one would have to agree that these sort of tours are, at the very least, entertaining.

Museum interpretation, in an ideal scenario, should be a fair balance between these two extremes. providing necessary information about a site and at the same time encouraging the ability to visualize what could have been there. What matters are the places where one inserts creative interpretation versus where one communicates factual information.

This is the point where art and historic sites can enter into a productive interpretive relationship. The inherent openness of art interpretation can serve as an antidote to the staleness of historic interpretation, and make a historic artifact become, momentarily, a found object that can acquire new meanings.

But how can we best handle this relationship without turning art into amateur history, or historical narratives into bad novels?

2. Downstairs: Facts and Lyrics of History

Elsa Lizalde, my aunt and my closest living relative in Mexico City, unexpectedly passed away this past summer. She was an opera lover, an authority in numismatics, a gourmet cook, and an unparalleled hostess. Always single, she spent her life traveling around Europe and spending her money on the best opera balconies and the best restaurant tables. Her overcrowded apartment was a perfect reflection of her personality: over the top, generous, and crowded with souvenirs from her travels and cultural life experiences.

It came upon me, my mother, and my sister to travel from the US to empty out Lizalde’s apartment, which had been the family home to four generations. Being the last in line of a long genealogy that broke when we emigrated to the US, my aunt left behind a true museum of family memorabilia that needed to be dealt with, as well as an enormous amount of things that she had accumulated throughout her life as part of her travels, her work, and her compulsive shopping. I thus went through the sad and somber task of selecting and eliminating an overwhelming amount of objects, books, and photographs. In general, however, most objects (old train tickets, ashtrays, European souvenirs, empty perfume bottles, concert program notes) had a symbolic or sentimental value that we could only imagine. And while we were often torn by the idea of disposing of those things that obviously had meant so much to her, we eventually had no option but to get rid of them.

When a person disappears, they take with them a whole world of meaning projected onto every object they once owned, and even if you are fastidious about memorializing, retaining these objects does little to recover the anecdotal stories that lie behind them.

While my aunt was alive, all these objects contained a private, albeit knowable, story, ranging from the silly and trivial to the truly commemorative and meaningful. Once she died, all those objects immediately became plain objects again (with the exception, of course, of those of which we happened to know their meaning and had our own personal attachment.) Certainly for a stranger who walked into her apartment at that point, the place looked like a museum of a typical upper-middle-class apartment of late twentieth-century urban Mexico. By studying the objects she owned, a researcher (or a detective-historian) could put together a somehow descriptive history of her taste, travels, profession, and hobbies. But with the exception of the stories that those close to her could tell, the specific “lyrics” of her life are now out of reach.

At the Tenement Museum in New York’s Lower East Side, most of the objects original to the building and people who lived there are gone. What we have is a historic structure that functions within the fabric of New York City in the same way than a romantic medieval ruin would function in England or Germany in the nineteenth-century, or the way in which most pre-Columbian ruins function in contemporary Latin America. It bears the marks of hundreds of stories and experiences, but paradoxically, we practically know nothing of them (other than the general facts of the period and parallel individual histories,) and we have not many options but to let the imagination run wild. With the exception of the few remaining anecdotes salvaged through the contact with living former residents (such as the Italian woman from the Confino family apartment,) who do give us a general sense of the life in those rooms, for the most part we can only rely on general historical data and research about the neighborhood. Most of the objects at the museum are not the original ones, but, rather, historical props that help support narrative interpretations about what happened there.

Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle famously wrote, "The history of the world is but the biography of great men," which is another way of saying that regular people aren’t even worth considering. History has often been preoccupied with writing the “great” narratives, and not so much with the personal stories of average people. In the case of a place like the Tenement Museum, whose protagonists were not famous people but average immigrants, there is a “lyrical vacuum” that we need to fill through interpretation and imagination.

But aside from the absence of stories, we need to find a significant contextual background against which these stories may come to life and become meaningful to others. Museums that contain the perfectly documented lives of historic figures can provide remarkably dull experiences, such as House of the Seven Gables was to me.

Even in today’s information age, where we may now witness the first generation in the world as they publicly document their own lives by the minute, all these infinite stories become a wash, canceling each other in a tumult of commonplace descriptions and situations. The only ones that emerge may have less to do with the content than with the way in which they have been told.

The best metaphor that I can think of to describe the way in which art plays the role of history is that of a tendentious dictionary: one that provides entirely subjective, and yet fairly concrete, responses to complex puzzles of time.

And it is against this paradox of history where art has stepped in, providing that interpretive appreciation. History may have given us the facts and the accurate theoretical evaluation about why certain things were the way they were, but the emotional character of certain historical ages have largely been artistic creations, such as the characters of Balzac and Dickens in the nineteenth century and Hollywood’s characters in the twentieth.

There is certainly something mischievous about the way in which art co-opts the historical narrative and turns it into a human story, because historical accuracy usually gives way to its dramatization, creating distorted perceptions of what may actually have happened, for the sake of art. From the tour guide in Teotihuacán making fabulous histories of moon goddesses and jaguars to Mel Gibson’s Apocalypto, history becomes a medium for art with varying degrees of historical credibility and too often the ability to influence our collective perception of historical episodes or events that may be complete fabrications. How can any historian now correct the perception that Mozart was the adolescent prankster as portrayed in Amadeus or that most people in turn-of-the-last-century Paris weren’t dancing rap-like rhythms as suggested in Moulin Rouge? It is a particularly irritating process when a complex historical narrative is turned into a cheap or oversimplified story. In this scenario, history tends to become something of an endorser for movies that make the vague claim of being “based on a true story,” as the story being told necessarily had a greater charge of reality than one purely inspired by imaginary events.

Art that plays the role of history may just underline the fact that academic historical narratives usually fail at connecting with the viewer on a personal level. What art really does, more than transporting us to another time and place, is to transport that time and place to our own time, translating it into our contemporary visual and narrative codes. And, in the case of absent historical data, art becomes a filler for those gaps. In the best cases, art doesn’t function like a replacement of history, but rather in its soul. It enacts a relationship that has existed from the earliest times: mythology is nothing but an artistic attempt to fill in an incomplete history. In the end, we can’t understand without interpretation, and we can’t interpret without creativity.

The best metaphor that I can think of to describe the way in which art plays the role of history is that of a tendentious dictionary: one that provides entirely subjective, and yet fairly concrete, responses to complex puzzles of time.

3. Upstairs: Foreign Pasts and Familiar Futures

British writer L. P. Hartley’s phrase “The past is like a foreign country: they do things differently there” adequately describes the familiarity and displacement that most people feel when they enter into a space like the Tenement Museum. We are twice removed from the reality we visit, both because it is distant in time and because it tells the stories of immigrants coming from distant places.

However, this phrase is also significant in the context of the historical site because it helps dispel the assumption that is communicated by traditional interpretation such as that enacted at the House of the Seven Gables: history is never a set narrative, but one in constant reinterpretation. Rather it is a set of markers with a multiplicity of meanings. While historical facts and figures may be unchangeable, our view of those facts is never the same. And facts alone can never transmit the essence of a place (like Elsa Lizalde’s apartment.)

“The future is not what it used to be” wrote nineteenth-century poet, Paul Valery. At a first glance, this is intended to be humorous. (By definition, the future can’t stop being what it was, because it can never occur before it happens.) What Valery is really talking about is that our own collective outlook of the future—or, rather, the cultural role that the notion of the future plays in our present time—is no longer regarded in the same way as it was in the past. The meaning of this phrase can be interesting to think about when we compare the attitudes towards the future that we’ve had over the generations. Can we claim to have the same degree of optimism that existed, say, in the US after World War II, or have we grown more cynical about what is to come?

In the context of today’s America and the current political situation, our national outlook feels bleaker than ever before. There is a sense that we keep making the same mistakes of the past. We may want to ask whether we are more detached from the past than we should be, or the reasons that post war American optimism has today turned into delusion in some and pessimism in others. The answers to those questions may vary widely, but most would agree that they lie in how we learn from the past and plan for the future.

While neither Valery nor Hartley may have had politics in mind, both may have agreed that our relationship with time is ever-shifting, and that things look different—sometimes to the point of seeming incomprehensible—as we move forward in time. And, in the same way that we may judge those who lived before us, so we will be judged by those who come after us. We are the future of the people who lived at what is now a museum, and we also are the past of those who will live in our own homes—which, who knows, may one day be turned into museums.

Cite this article as

Chicago Style

MLA Style

Shareable Link

Copy this page's URL to your clipboard.

Created under the direction of Pablo Helguera, this chapter accompanies the exhibition Raid the Icebox Now with Pablo Helguera: Inventarios / Inventories, on view at the RISD Museum February 7 - July 19, 2020. Creative direction by Carolyn Gennari. Curatorial support by Sarah Ganz Blythe. Design and illustrations by Carson Evans. Additional production support by Erik Gould, Jeremy Radtke, and Arielle Eisen. Special thanks to Ramuntcho Matta for the use of excerpts from his film, Intimatta.

Exhibition photography by Erik Gould.

All video of Roberto Matta comes from the film, Intimatta, by Ramuntcho Matta.

Photograph used in the portrait illustration of Luis González Palma courtesy of the artist.

Photograph used in the portrait illustration of Miguel Angel Ríos courtesy of the artist.

Photograph used in the portrait illustration of Arnaldo Roche Rabell courtesy of the artist's estate.

Photograph used in the portrait illustration of Alfredo Castañeda courtesy of the artist's estate.