The practice of drawing in 19th-century America was defined by change and innovation. American artists went from learning in relative isolation to a time of expansive educational prospects, including drawing schools and teachers, instructional manuals, and opportunities for travel abroad. Resources expanded with the introduction of readily available tube paints, prepared watercolor cakes, graphite pencils, steel-nib pens, conté crayons, and new fixatives and papers.

Topographic, folk, and academic traditions dominated American drawing before 1850. Today, these precisely drawn topographical views provide valuable records of places full of potential, before industrialization. Folk drawings highlight the importance of local traditions, portraiture, and religious and historical subject matter to American patrons.

Artists working after 1850, whose drawings dominate this gallery, were significantly influenced by the English critic John Ruskin’s manual Elements of Drawing (1857), which emphasized meticulous attention to the individual details of nature. A number of American artists traveled to Düsseldorf and Munich, Germany, where they too were trained in the close observation of nature via the practice of drawing.

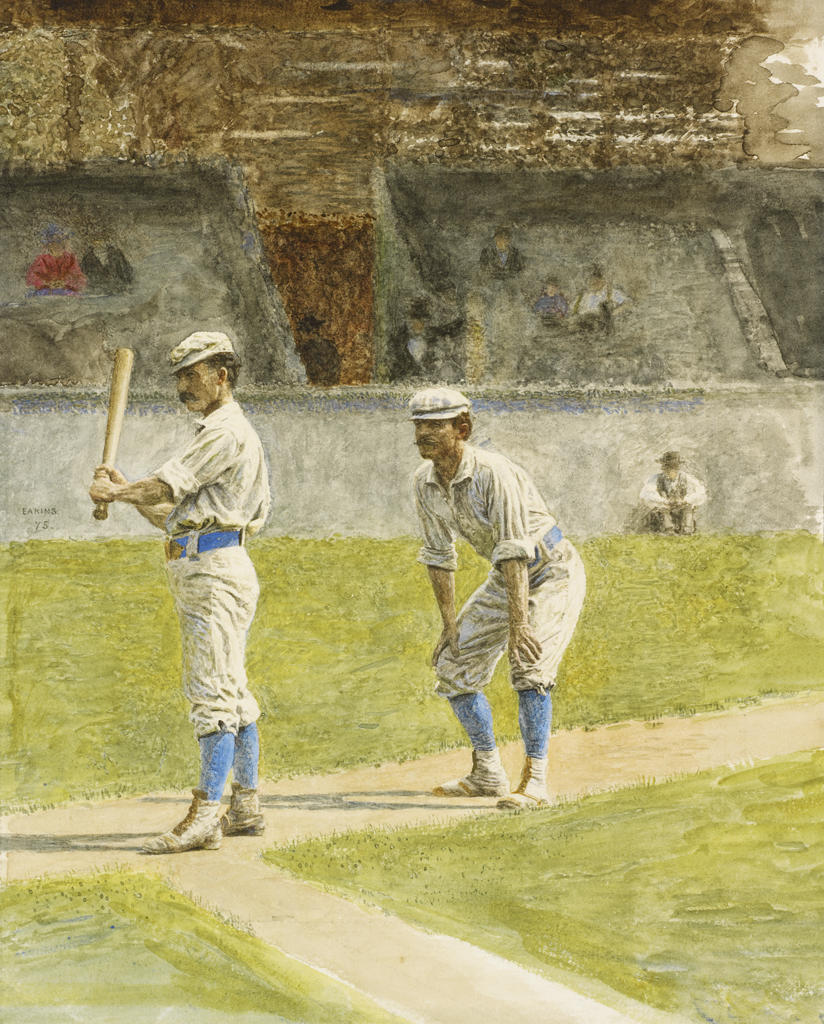

Such emphases migrated naturally to the focus on landscape as a subject. Leisure pursuits, ranging from team sports to hunting to childhood amusements, many with landscape as a secondary theme, also dominated the scene. Artists showed their work in societies dedicated to drawing and especially to the medium of watercolor in New York, Philadelphia, and Providence. The evolution of watercolor as a versatile medium for reproducing the effects of nature—advocated by Ruskin, and others—stands as the most significant phenomenon in 19th-century American drawing of any subject. The fluid, transparent effects developed by artists working at the end of the century shaped a uniquely American style.